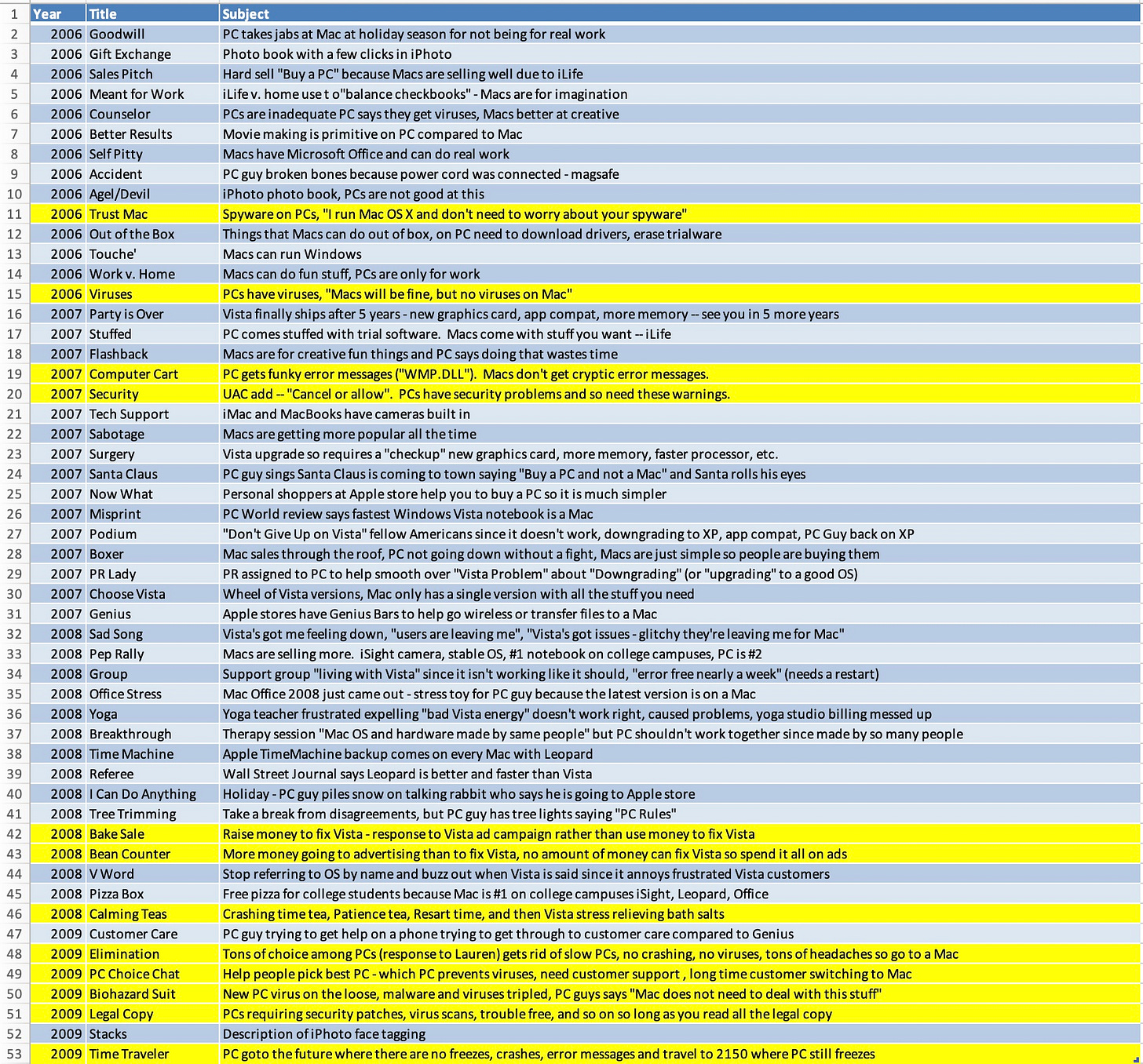

090. I’m a Mac

“I’m a PC.” — Microsoft’s response to Apple’s “Get a Mac” campaign

Advertising is much more difficult than just about everyone believes to be the case. In fact, one of the most challenging tasks for any executive at any company is to step back and not get involved in advertising. It is so easy to have opinions on ads and really randomize the process. It is easy to see why. Most of us buy stuff and therefore consume advertising. So it logically follows, we all have informed opinions, which is not really the case at all. Just like product people hate everyone having opinions on features, marketing people are loathe to deal with a cacophony of anecdotes from those on the sidelines. Nothing would test this more for all of Microsoft than Apple’s latest campaign that started in 2006. I’d already gone through enough of watching advertising people get conflicting and unreconcilable feedback to know not to stick my nose in the process.

Back to 089. Rebooting the PC Ecosystem

“I’m a Mac.”

“And, I’m a PC.”

The “Get a Mac” commercials, starting in 2006, changed the competitive narrative overnight and were a painful gut punch welcoming me to Windows.1

They were edgy, brutal in execution, and they skewered Windows with facts. They were well done. (Though it always bothered me that PC Guy had a vague similarity to the late and much-loved Paul Allen, Microsoft’s cofounder long focused on science and philanthropy.) Things that drove Windows fans crazy like “no viruses” on Mac were not technically true, but true in practice because, mostly, why bother writing viruses for Macs with their 6 percent share? That’s what we told ourselves. In short, these commercials were devastating.

They probably bumped right up against a line, but they effectively tapped into much of the angst and many of the realities of PC ownership and management. Our COO and others were quite frustrated by them and believed the commercials not only to be untrue, but perhaps in violation of FTC rules.

They were great advertising. Great advertising is something Apple seemed to routinely accomplish, while Microsoft found it to be an elusive skill.

For its first twenty years, Microsoft resisted broad advertising. The company routinely placed print ads in trade publications and enthusiast magazines, with an occasional national newspaper buy for launches. These ads were about software features, power, and capabilities. Rarely, if ever, did Microsoft appeal to emotions of buyers. When Microsoft appeared in the national press, it was Bill Gates as the successful technology “whiz kid” along with commentary on the growing influence and scale of the company.

With that growing influence in the early 1990s and a business need to move beyond BillG, a huge decision was made to go big in advertising. Microsoft retained Wieden+Kennedy, the Portland-based advertising agency responsible for the “Just Do It” campaign from Nike, among many era-defining successes. After much consternation about spending heavily on television advertising, Microsoft launched the “Where do you want to go today?” campaign in November 1994.

Almost immediately we learned the challenges of advertising. The subsidiaries were not enamored with the tagline. The head of Microsoft Brazil famously pushed back on the tagline, saying the translation amounted to saying, “do you want to go to the beach today?” because the answer to the question “Where do you want to go?” in Brazil was always “the beach.” The feedback poured in before we even started. It was as much about the execution as the newness of television advertising. Everyone had an opinion.

I remember vividly the many pitches and discussions about the ads. I can see the result of those meetings today as I rewatch the flagship commercial. Microsoft kept pushing “more product” and “show features” and the team from W+K would push back, describing emotions and themes. The client always wins, and it was a valuable lesson for me. Another a valuable lesson, Mike Maples (MikeMap) who had seen it all at IBM pointed out just before the formal go ahead saying something like “just remember, once you start advertising spend you can never stop. . .with the amount of money we are proposing we could hire people in every computer store to sell Windows 95 with much more emotion and information. . .” These were such wise words, as was routine for Mike. He was right. You can never stop. TV advertising spend for a big company, once started, becomes part of the baseline P&L like a tax on earnings.

The commercials were meant to show people around the world using PCs, but instead came across almost cold, dark, and ominous as many were starting to perceive Microsoft. That was version 1.0. Over the next few years, the campaign would get updates with more colors, more whimsy, and often more screenshots and pixels.

What followed was the most successful campaign the company would arguably execute, the Windows 95 launch. For the next decade, Microsoft would continue to spend heavily, hundreds of millions of dollars per year, though little of that would resonate. Coincident with the lukewarm reception to advertising would be Microsoft’s challenges in branding, naming, and in general balancing speeds and feeds with an emotional appeal to consumers. Meanwhile, our enterprise muscle continued to grow as we became leaders in articulating strategy, architecture, and business value.

In contrast, Apple had proven masterful at consumer advertising. From the original 1984 Superbowl ad through the innovative “What’s on your PowerBook?” (1992) to “Think Different” (1997-2000) and many of the most talked about advertisements of the day such as “C:\ONGRTLNS.W95” in 1995 and “Welcome, IBM. Seriously” in 1981, Apple had shown a unique ability to get the perfect message across. The only problem was that their advertising didn’t appear to work, at least as measured by sales and/or market share. The advertising world didn’t notice that small detail. We did.

Starting in 2006 (Vista released in January 2007), Apple’s latest campaign, “Get a Mac” created an instant emotional bond with everyone struggling with their Windows PC at home or work, while also playing on all the stereotypes that existed in the Windows v. Mac battle—the nerdy businessman PC slave versus the too cool hipster Mac user.

The campaign started just as I joined Windows. I began tracking the commercials in a spreadsheet, recording the content and believability of each while highlighting those I thought particularly painful in one dimension or another. (A Wikipedia article would emerge with a complete list, emphasizing the importance of the commercials.) I found myself making the case that the commercials reflected the state of Windows as experienced in the real world. It wasn’t really all that important if Mac was better, because what resonated was the fragility of the PC. There was a defensiveness across the company, a feeling of how the “5% share Mac” could be making these claims. I managed a bit of a row with the COO who wanted to go to the FTC and complain that Apple was not telling the truth.

Windows Vista dropped the ball. Apple was there to pick it up. Not only with TV commercials and ads, but with a resurging and innovative product line, one riding on the coattails of Wintel. The irony that the commercials held up even with the transition to Intel and a theoretically level playing field only emphasized that the issue was software first and foremost, not simply a sleek aluminum case.

While the MacBook Air was a painful reminder of the consumer offerings of Windows PCs, the commercials were simply brutal when it came to Vista. There were over 50 commercials that ran from 2006-2009, starting with Apple’s transition to Intel and then right up until the release of Windows 7 when a new commercial ran on the eve of the Windows 7 launch. Perhaps the legacy of the commercials was the idea that PCs have viruses and malware and Macs do not. No “talking points” about market share or that malware targets the greatest number of potential victims or simply that the claim was false would matter. There’s no holding back, this was a brutal takedown, and it was effective. It was more effective in reputation bashing, however, than in shifting unit share.

One of the most memorable ones for me was “Security” which highlighted the Windows Vista feature designed to prevent viruses and malware from sneaking on your PC, called User Account Control or UAC which had become a symbol of the annoyance of Vista—so much so our sales leaders wanted us to issue a product change to remove it. There’s some irony in that this very feature is not only implemented across Apple’s software line today, but far is more granular and invasive. That should sink in. Competitively we all seem to become what we first mock.

Something SteveB always said when faced with sales blaming the product group and the product group blaming sales for something that wasn’t working, was “we need to build what we can sell, and sell what we build.” Windows Vista was a time where we had the product and simply needed to sell what we had built, no matter what.

The marketing team (an organization peer to product development at this time) was under a great deal of pressure to turn around the perceptions of Vista and do something about the Apple commercials. It was a tall order. The OEMs were in a panic. It would require a certain level of bravery to continue to promote Vista, perhaps not unlike shipping Vista in the first place. The fact that the world was in the midst of what would become known as the Global Financial Crisis with PC sales taking a dive did not help.

Through a series of exercises to better come up with a point of attack the team came up with the idea that maybe too many people were basing their views of Windows Vista on hearsay and not actual experience. We launched a new campaign “Mojave Experiment” that took a cinéma vérité approach to showing usability studies and focus groups for yet to be released and experimental version of Windows Mojave. After unsolicited expressions of how bad Vista was, the subjects were given a tour of Windows Mojave. The videos were not scripted, and the people were all real, as were the reactions. Throughout the case study, and the associated online campaign, the subjects loved what they were being shown. Then at the end of the videos, the subjects were told the surprise—this was Windows Vista. To those old enough to know, it had elements of the old “Folger’s Coffee” or “I Can’t Believe It’s Not Butter” commercials, classic taste-test advertising.

The industry wasn’t impressed. In fact, many took to blog posts to buzzsaw the structure of the tests and way subjects were questioned and shown the product. One post in a Canadian publication ran with the headline “Microsoft thinks you’re stupid” in describing the campaign. This was right on the heels of the Office campaign where we called our customers dinosaurs. We had not yet figured out consumer advertising.

We still had to sell the Vista we had built. We needed an approach that at the very least was credible and not embarrassing, but importantly at least hit on the well-known points about Apple Macintosh that everyone knew to be true. Macs were expensive and as a customer your choices were limited.

Apple’s transition to Intel was fascinating and extraordinarily well executed, releasing PCs that were widely praised, featuring state-of-the-art components, an Intel processor unique to Apple at launch, and superior in design and construction to any Windows PC. The new premium priced Intel Macs featured huge and solid trackpads, reliable standby and resume, and super-fast start-up. All things most every Windows PC struggled to get right. We consistently found ourselves debating the futility of the Apple strategy offering expensive hardware. The OEMs weren’t the only ones who consistently believed cheaper was better, but that was also baked into how Microsoft viewed the PC market. Apple had no interest in a race to profitless price floors and low margins, happily ceding that part of the market to Windows while selling premium PCs at relatively premium prices. In fact, their answer to the continued lowering of PC prices was to release a pricey premium PC.

The original MacBook Air retailed for what seemed like an astonishing $1,799. That was for the lowest specification which included a 13” screen and a meager 2GB main memory, an 80GB mechanical hard drive, and a single USB port and obscure video output port, without an DVD drive or network port. For an additional $1000, one could upgrade to a fancy new solid state disk drive which was still unheard of on mainstream Windows PCs.

As it would turn out the MacBook Air was right in the middle of the PC market, and that’s just how PC makers liked it, stuck between the volume PC and premium PC, neither here nor there. An example of most popular laptop configuration was the Dell Inspiron 1325. The 1325 was a widely praised “entry level” laptop with an array of features, specs, and prices. In fact, on paper many PC publications asked why anyone would buy an overpriced Macintosh. The Dell 1325 ranged in prices from $599 to about $999 depending on how it was configured. The configuration comparable to a MacBook Air was about $699 and still had 50% more memory and three times the disk space. As far as flexibility and ports, the 1325 featured not just a single USB port but two, a VGA video connector, audio jacks, Firewire (for an iPod!), an 8 in 1 media card reader, and even something called an ExpressCard for high-speed peripherals. Still, it was a beast, while the same width and length it was twice as thick and clearly more dense weighing almost 5lbs at the base configuration compared to the 3lb MacBook Air. As far as battery life, if you wanted to be comparable to the Air then you added a protruding battery that added about a pound in weight and made it so the laptop wouldn’t fit in a bag. Purists would compare to the MacBook (not the Air), as we did in our competitive efforts, but the excitement was around the Air. The regular 13” MacBook weighed about 4.5lbs and cost $1299, which would make it a more favorable comparison. It was clear to me that the Air was the future consumer PC as most PC users would benefit from lighter weight, fewer ports, and a simpler design. As much as I believed this, it would take years before the PC industry broadly recognized that “thin and light” was not a premium product. The MacBook Air would soon end up priced at a $999 entry price, which is when it began to cause real trouble for Windows PCs.

The higher-end MacBook Air competitor from the PC world was the premium M-series from Dell. Incidentally, I’m using Dell as an example, HP and Lenovo would be similar in most every respect. The Dell XPS M1330, the forerunner to today’s wonderful Dell XPS 13, was a sleeker 4lbs also featuring a wedge shape. With the larger and heavier battery there was a good 5 hours of runtime. Both Dells featured plastic cases with choices of colors. It too had models cheaper than the MacBook or MacBook Air but could be priced significantly more by adding more memory, disk storage, better graphics, or a faster CPU.

A key factor in the ability for the Mac to become mainstream, however, was the rise in the use of the web browser for most consumer scenarios. A well-known XKCD cartoon featured two stick figures, one claiming to be a PC and another claiming to be a Mac, with the joint text pointing out “and since you do everything through a browser now, were pretty indistinguishable.”2 Apple benefitted enormously from this shift, or disruption, especially as Microsoft continued to invest heavily in Office for the Mac. The decline in new and exciting Windows-based software described in the previous section proved enormously beneficial to Apple when it came to head-to-head evaluation of Mac versus Windows. Simply running Office and having a great browser, combined with the well-integrated Apple software for photos, music, videos, and mail proved formidable, and somewhat enduring with the rise in non-PC devices.

We were obsessed with the pricing differences. We often referred to these higher prices as an “Apple Tax” and even commissioned a third party to study the additional out of pocket expenses for a typical family when buying Macs versus Windows PCs. A whitepaper was distributed with detailed comparison specifications showing the better value PCs offered. In April 2008 we released a fake tax form itemizing (groan) the high cost of Apple hardware.

From our perspective or perhaps rationalization this was all good. Consumers had choice, options, and flexibility. They could get the PC they needed for their work and pay appropriately, or not. This thesis was reinforced by the sales of both PCs and Macs no matter what anyone was saying in blogs. The PC press loved this flexibility. Retailers and OEMs relied on the variety of choices to maximize margin. Retailers in particular struggled with Apple products because they lacked key ways to attach additional margin, such as upsell or service contracts, not to mention Apple’s lack of responsiveness to paying hefty slotting and co-advertising fees.

Choosing a PC while a complicated endeavor was also the heart and soul of the PC ecosystem. Once Apple switched to Intel, there was a broad view that the primary difference between Mac and Windows now boiled down to the lack of choice and high price and lack of a compatible software and peripheral ecosystem that characterized Macintosh.

To make this point, Microsoft launched a new campaign the “Laptop Hunter” that ran in 2009. In these ads, typical people are confronted outside big box retailers trying to decide what computer to buy. A PC or a Mac? In one ad, “Lauren” even confesses she is not cool enough for a Mac while noticing just how expensive they are (NB, Lauren is almost the perfect representation of a Mac owner.) She heads over to a showroom with a vast number of choices and whittles her way down to a sub $1000 PC with everything she needs. Another success.

Not to belabor this emerging theme, but no one believed these ads either. Only this time, the critics and skeptics were livid as it appeared Lauren was an actress and that called into question the whole campaign. In addition, Apple blogs went frame-by-frame in the ad to “prove” various aspects of the shoot were staged or simply not credible. The tech blogs pointed out the inconsistencies or staged aspects of Lauren’s requirements as being designed to carefully navigate the Apple product line.

Laptop Hunter offers some insight into how addictive (or necessary) television advertising became and the scale at which Microsoft was engaging. The television campaign debuted during the NCAA basketball tournament in the US, prime time. It was supported by top quality network prime shows (Grey's Anatomy, CSI, The Office, Lost, American Idol), late night staple programming (Leno, Letterman, Kimmel, Conan, and Saturday Night Live) and major sports events and playoff series (NCAA Basketball, the NBA, MLB, and the NHL). Cable networks included Comedy Central, Discovery, MTV, VH1, History and ESPN. The online campaign included home page execution on NYTimes.com, as well as “homepage take-overs” (the thing to do back then) on WSJ, Engadget, and CNN. We also supported this with an online media buy targeted at reaching people who were considering a non-Windows laptop (a Mac). We linked from those banner ads to a dedicated Microsoft web site designed to configure a new PC and direct to online resellers, closing the loop to purchase. The level of spending and effort was as massive as the upside.

I could defend the advertising but at this point I am not sure it is worth the words. Besides, Apple responded to the ad with a brutal reiteration of viruses and crashes in PCs and that lots of bad choice is really no choice at all. It is rare to see two large companies go head-to-head in advertising and you can see how Microsoft took the high road relative to Apple, deliberately so. The ads worked for Apple, but almost imperceptibly so in the broader market. Apple gained about one point of market share, which represented over 35% growth year over year for each of the two years of the campaign—that is huge. The PC market continued to grow, though at just over 10%. Still that was enough of a gain to ameliorate the share gains from Apple, which were mostly limited to the US and western Europe.

As much as the blowback from this campaign hurt, we were at least hitting a nerve with Apple fans and getting closer to a message that resonated with the PC industry: compatibility, choice, and value.

For our ad agency, essence of the PC versus Mac debate boiled down not to specs and prices but to a difference in the perceived customers. The Mac customers (also the agency itself) seemed to be cut from one mold of young, hip, artistic whereas the PC was literally everyone else. It seemed weird to us, and our advertising agency, that Windows computers were not given credit for the wide array of people and uses they supported, if even stereotypically. We were proud of all the ways PCs were used.

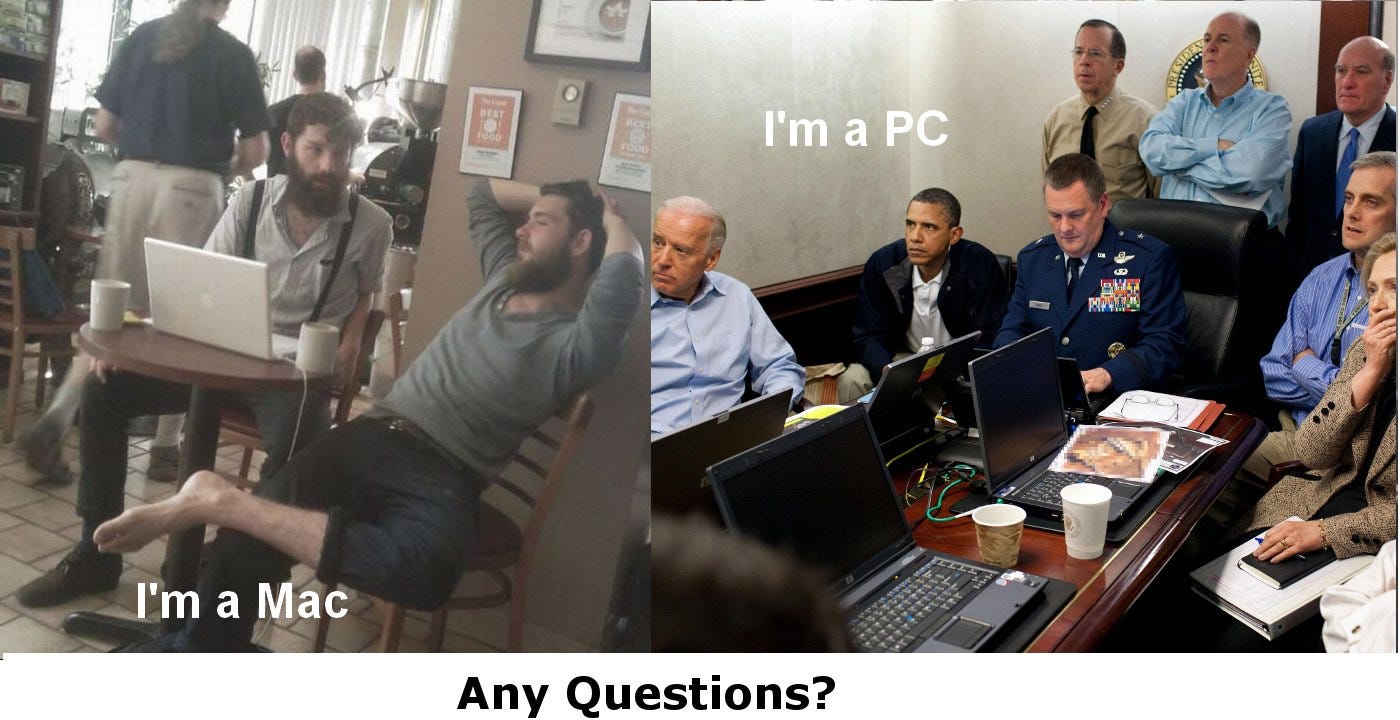

To demonstrate this pride, Bill Veghte (BillV) the senior vice president of Windows marketing (also reporting to Kevin Johnson) led the creation of a new “I’m a PC” campaign that started in the fall of 2008 and ran through the launch of Windows 7. Rather than run from the Apple’s “I’m a Mac” we embraced it. The main spot featured fast cuts of people from all walks of life, including members of the Microsoft community as well as some pretty famous people, talking about their work, creations, and what they do with PCs. The ads featured a Microsoft employee, Sean Siler a networking specialist from Microsoft Federal, who looked unsurprisingly like the stereotype PC users portrayed by Apple. These ads were us.

The advertising world viewed success through the creative lens so dominated by Apple. The ads were well-received and for the first time we landed spots (costing hundreds of millions of dollars) that we could both be proud while emphasizing our strengths.

The memorable legacy of the campaign would be the brightly colored “I’m a PC” stickers that nearly everyone at the company dutifully attached to their laptops. Meeting rooms filled with open laptops of all brands, colors, sizes all displayed the sticker. We made sure all of our demo machines featured the stickers as well. In the summer 2009 global sales meeting just before Windows 7 would launch, BillV led the sales force in a passionate rally around “I’m a PC” and the field loved it. He was in his element, and they were pumped. The Windows 7 focused versions of this campaign featured individuals talking about their work saying “I’m a PC and Windows 7 was my idea” building on the theme of how Windows 7 better addressed customer needs (more on that in the next chapter.)

By the summer of 2009, the back and forth with Apple seemed to run its course as we were close to the launch of Windows 7 (more on that in the next chapter.) The New York Times ran a 3000-word, front of the Sunday business section story titled “Hey, , PC, Who Taught You to Fight Back?” covering what was portrayed as an “ad war, one destined to go down in history with the cola wars of the 1980s and ’90s and the Hertz-Avis feud of the 1960s.”3 There was even a chart detailing the escalating advertising spend of the two companies. The story even noted that the ads caught the attention of Apple who pulled their ads from the market only to return with new “Get a Mac” ads criticizing Microsoft’s ads. In the world of advertising, that counts as a huge victory. On the store shelves, the campaign finally seemed to at least slow the share loss to Apple worldwide and definitely pushed it back in the US.

Nothing hit home more a few years later than the photo of the White House situation room in May 2011 during the raid on Osama Bin Laden. That photo was captioned by the internet to illustrate the point of just who is a Mac and who is a PC. The meme featured some barefooted hipsters in a coffee shop captioned “I’m a Mac” and then the situation room featured secured PCs captioned “I’m a PC” with the heading “Any Questions?” We loved it. That seriousness was what we were all about.

Of course, the real battle with Apple was now about software. Windows 7 needed to execute. We needed to build out our services offerings for mail, calendar, storage, and more where Apple was still flailing even more than we were.

While I was entirely focused on Windows 7 and moving forward, the ghosts of Vista and Longhorn would appear. Promises were made that ultimately could not be kept and we had to work through those.

On to 091. Cleaning Up Longhorn and Vista

Postscript. The “Get a Mac” ad that hit me the hardest for non-product reasons was the “Yoga” spot, which was funny to me because when I moved to Windows in March 2006 I switched to practicing yoga after a decade of Pilates. In the spot, PC guy switches from yoga to Pilates.

The “Get a Mac” commercials were scraped from various sites online and collected on Vimeo to preserve the content.

https://xkcd.com/934/

”Hey, PC, Who Taught You to Fight Back?”, by Devin Leonard, New York Times, August 30, 2009

Super awesome article, thank you.