089. Rebooting the PC Ecosystem

“We needed to move from saying what we were thinking to saying what we were doing.” —Mike Angiulo (MikeAng), CVP Windows Planning and Ecosystem

The word ecosystem is often used when describing Windows and the universe of companies that come together to deliver Windows PCs and software. Providing a platform is a much trickier business than most might believe. Bringing together a large number of partners, along with their competitors, who might share one large goal but differ significantly in the tactics to use to achieve it is fraught with conflict. The Windows ecosystem had been dealt a series of painful blows over the years resulting in a loss of trust and collective capability. Where partnerships were required, the ecosystem had become a collection of…adversaries…or direct competitors…or conflicting distribution channels.

Back to 088. Planning the Most Important Windows Ever

In the summer of 2007 six-months after Windows Vista availability as we rolled out the Windows 7 product vision to the entire team, the press coverage for Vista began to get brutal. I say the coverage, but this is really about the customer reaction to the product and the press simply reflected that.

![Disappointed With Windows Vista" Just a day after analyst firm Net Applications released figures showing that Windows Vista now enjoys a 5 percent share of the online market, Acer president Gianfranco Lanci criticized Microsoft's new OS saying, "the whole industry is disappointed with Windows Vista. Despite the fact that if Vista's adoption trend continues, it should pass Mac OS [...] f V Just a day after analyst firm Net Applications released figures showing that Windows Vista now enjoys a 5 percent share of the online market, Acer president Gianfranco Lanci criticized Microsoft's new OS saying, "the whole industry is disappointed with Windows Vista." Despite the fact that if Vista's adoption trend continues, it should pass Mac OS X by the end of August Lanci is critical of the system. According to PC World, Lanci's beef is not about market share but stability and other issues. Lanci says Vista is riddled with problems and gives users and businesses no reason to buy a new PC. Lanci also claims that Acer, the four largest manufacturer of PCs, has been inundated with customer requests for XP instead of Vista. Lanci's beef with Vista will take on more significance come January 2008 which is when Microsoft says it will no longer offer Windows XP to resellers, which means users who want to stay on XP will need to pony up for an additional copy to replace a new machine's pre-installed copy of Vista. Disappointed With Windows Vista" Just a day after analyst firm Net Applications released figures showing that Windows Vista now enjoys a 5 percent share of the online market, Acer president Gianfranco Lanci criticized Microsoft's new OS saying, "the whole industry is disappointed with Windows Vista. Despite the fact that if Vista's adoption trend continues, it should pass Mac OS [...] f V Just a day after analyst firm Net Applications released figures showing that Windows Vista now enjoys a 5 percent share of the online market, Acer president Gianfranco Lanci criticized Microsoft's new OS saying, "the whole industry is disappointed with Windows Vista." Despite the fact that if Vista's adoption trend continues, it should pass Mac OS X by the end of August Lanci is critical of the system. According to PC World, Lanci's beef is not about market share but stability and other issues. Lanci says Vista is riddled with problems and gives users and businesses no reason to buy a new PC. Lanci also claims that Acer, the four largest manufacturer of PCs, has been inundated with customer requests for XP instead of Vista. Lanci's beef with Vista will take on more significance come January 2008 which is when Microsoft says it will no longer offer Windows XP to resellers, which means users who want to stay on XP will need to pony up for an additional copy to replace a new machine's pre-installed copy of Vista.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!E24p!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Faec71738-f115-4f92-9afe-3327eb6dea1a_1692x2022.png)

Then the OEMs, large public companies with shareholders and quarterly earnings, started to do something almost unimaginable. They began to speak out about the problems with Vista. In a widely covered interview in the Financial Times discussing quarterly results, Acer president Gianfranco Lanci lashed out at Vista, saying the “whole industry is disappointed with Windows Vista" and stated that Vista had stability problems and he doubted that Microsoft would remedy the issues within the next six months. He went on to suggest that customers really wanted Windows XP knowing that in just a few months XP would be discontinued.1 Much of what he said in public, the OEMs had been telling us in private.

I had been in my role for more than a year and still did not have much to say about what was coming next. How could I? We just didn’t know and all my experience with customers told me that claiming I didn’t know would not be acceptable or even credible. Still, pressure was mounting to show progress.

The Windows (or PC) ecosystem is made up Intel, PC makers (the OEMs), and creators hardware components and peripherals known as Independent Hardware Vendors (IHVs). OEMs accounted for the vast majority of Microsoft’s extremely lucrative Windows business. IHVs were the key ingredients the OEMs counted on for innovation. Intel, provider of CPUs and an increasing portion of the main componentry, was the most central in the hardware ecosystem as half of the legendary Wintel partnership.

Suffice it to say ecosystem was in an unhappy and untrusting state after years of product delays along with a series of feature, product, and pricing miscues. The delays had been extremely painful to OEMs and Intel, who counted on a new release of Windows to show off new PCs and drive growth in PC sales. IHVs had critical work to do enabling new PCs. They had to build software drivers that enabled new hardware that was compatible with the new features of Windows (such as 64-bit Windows or new security features). They also faced the increasing complexity of maintaining drivers for old versions of Windows as the time between releases increased and customers demanded new hardware support on both old and new platforms. The rise of Linux was spreading the Windows ecosystem further as demand for Linux support increased. Fractures were everywhere.

Intel contributed an increasingly larger portion of the PC, much as Microsoft continued to add features to Windows. With Centrino® for example, Intel added WiFi support directly to the components they provided to PC makers. This greatly expanded and standardized the use of WiFi in laptops. Intel was in the process of broadening their support for graphics as well, continuing to improve the integrated graphics chips they provided to PC makers (this was a particularly sore spot with Vista.) Intel was able to better control pricing of their components, encourage specific PC designs, and shift PC makers to various CPU choices using a combination of pricing actions and co-marketing arrangements. Originally these “Intel Inside” advertising efforts were a huge part of how PC makers selected and marketed different models and lines of computers and was enormously profitable for Intel.

Microsoft’s relationship with Intel had not been particularly happy, going way back to the 1990s when Intel began to embrace Java and other cross-platform technologies. Recently, however, the rise of Linux was viewed by Intel as a large opportunity, while Microsoft perceived it as a competitive threat. What Microsoft used to perceive as a moat, device driver support for Windows, was rapidly fading due to active efforts by Intel to support Linux to the same degree. The specter of desktop Linux seemed to be held back by just a few device drivers should Intel support them, or so we worried.

There was also a complex relationship between enterprise customers and Microsoft when it came to Windows. From a product and feature perspective, Windows was making increasing bets on the kind of features businesses cared about, such as endpoint control, reliability, and management. Microsoft did not always want to give away those features for free to retail customers where they might not apply. The fact that these features existed caused OEMs to consider ways to add them to the base Windows they sold, feeling that the base Windows was under-powered. In other words, features Microsoft added to premium editions of Windows simply served as starting points for features OEMs might look to provide with their own software on top of the basic editions of Windows, increasing OEM margin.

The response to the increasing gap between consumers and enterprise was another reason for OEMs to embrace, or at least appear to embrace Linux. At the very least, OEMs began to ponder the idea of selling PCs with free Linux and letting customers pick and choose an operating system on their own as a backdoor way to avoid the Windows license for every single PC. Microsoft did not want OEMs selling PCs without Windows when Windows was destined to be on the PC anyway, as that would only encourage piracy. This “Linux threat” was not as empty as the state of technology would have indicated as OEMs were actively starting to offer Linux on the desktop, especially if they were offering it on Server already. Some markets, such as China, which already had enormously high piracy pursued this path aggressively.

From the least expensive PCs for the budget conscious to the fanciest PCs for gamers, the Windows product and business depended on these partners, and vice versa. Any business book would tell you just how big a deal the Windows ecosystem was, as would anyone who followed the antitrust actions against Microsoft.

We needed to reboot the relationship with and across the Ecosystem. Doing so would be an important part of the planning process and run in parallel with planning the Windows 7 product.

The perspectives, insights, and data from hardware and OEM partners were only part of the input to the planning process. Another part was the usage data from tens of millions of Windows users. What features, peripherals, and third-party programs were used, how often, and by which types of customers. Vista had done excellent work to incorporate the performance and reliability measures of the system, especially for glitches like crashes and hangs, but usage data was inconsistent across the system. As we would discover, this data was not readily available or reliably collected across the whole product. We knew we would need as much as we could for Windows 7 and certainly down the road, so we began in earnest to implement more telemetry across the product during the planning for Windows 7. This data would form a foundation for many discussions with OEMs.

The feverish pace and tons of work over the six months that followed the re-org tackled an expansive set of potential areas and distilled them down to a product plan, the Windows 7 Vision. That six months would bump up against not one but two OEM selling seasons during which the OEMs would not get the news about “fixing Vista” they were hoping for. The planning memo came out in December 2006 even before Windows Vista availability. That timing, however, would be too late to impact the February selling season. The July 2007 Vision was too late to become requirements for PCs for back to school in August or September of that year. Even though PCs would not ship with Windows 7 for quite some time, every selling season we missed would make it frustratingly difficult for those PCs to be upgraded to Windows 7. This was a problem for every part of the ecosystem including Microsoft.

The relationships were difficult, but more importantly the quality of work across the ecosystem was in decline. Communication was adversarial at best.

Mike Angiulo (MikeAng) joined from Office and began an incredible effort at rebuilding the relationships with OEMs. Mike was not only a stellar technologist, but a strategic relationship manager, having grown up as a salesman within his future family’s business. He was also a trained mechanical engineer who rebuilt and raced cars, a natural-born poker champion, and an IR-pilot who built his own plane.

He recruited Roanne Sones (RSones) to lead the rehabilitation of the relationship with OEM customers. She was a college hire from Waterloo’s prestigious systems engineering program who had joined Office five years earlier. Having worked on projects from creating the Office layperson’s specification, to synthesizing customer needs by segment, to analyzing usage data across the product, Roanne brought a breadth of tools and techniques from Office to the OEM problem space. Also joining the team was Bernardo Caldas (BCaldas) who would bring deep insights combining usage data, financial modeling, and business model thinking to the team.

Roanne quickly learned that a big part of the challenge would be the varying planning horizons the OEMs required. “Required” because they told us that they needed “final Windows 7 plans” in short order if they were to make the deadlines for a selling season. Whether they needed the information or not, the reality was they were so used to not getting what they wanted they simply made any request urgent and expansive.

Each OEM was slightly different in how it approached the relationship, but all shared two key attributes. First, they viewed Windows as an adversary. Second, they did not take anything we told them to be the ground truth. They were constantly working the Microsoft organization and their connections, which were deep, across the separately organized OEM sales team, support organizations, and more, to triangulate anything we said to arrive at their own version of truth or reality. They also had no problems escalating to the head of global sales or to SteveB directly, several of whom had known Steve for decades.

After a decade of missed milestones, dropped features, antitrust concerns, and contentious business relationships, the connection between Microsoft and OEMs was painfully dysfunctional. Considering Windows accounted for so much of Microsoft’s profit, this was a disaster of a situation. It had been going on so long that most inside Microsoft seemed to shrug it off as just a part of the business or “OEMs have always been like this.” It was no surprise to me that the relationships devolved.

We found little to love in most new PCs while at the same time Microsoft was rooted in a long history of believing, as BillG would say though this is misinterpreted I think, that “ten years out, in terms of actual hardware costs you can almost think of hardware as being free.”2 He meant that to imply that relative to advancing software capabilities, the hardware resources required would not be a key factor in innovation. I’m not sure OEMs heard it that way.

What was really going on other than Microsoft’s lack of reliability as a partner, not to dismiss that perfectly legitimate fact? It goes back to the history of PC manufacturing and its evolution to the current situation. When Dell and then Compaq first manufactured PCs, they were rooted in engineering and design of PCs, and each built out manufacturing and distribution channels—PCs made in the US (Texas) and shipped around the world.

As the industry matured, more and more manufacturing moved to plants in Taiwan and China. Traditionally, components such as hard drives, accessory boards, and motherboards were shipped to the United States from locations around Asia for final assembly, including the addition of the Intel CPU manufactured in the US. Eventually, as more and more were made in Asia, it became increasingly efficient to aggregate components there for assembly as a complete PC, which could then be shipped around the world. This transition is one Tim Cook, now the CEO of Apple, famously took Apple through even though Steve Jobs resisted it.

Over time, these assembly companies aimed to deliver even more value and a greater share of the PC experience, as they described. They even began to create speculative PCs and sell them to the OEMs, such as Dell and HP for incorporation into their product lines after a bit of customization such as component choice and industrial design. The preference for laptops over desktops made it even more critical to engineer a complete package, which these new original design manufacturer partners became experts at doing. As the name implied, an ODM would both design and manufacture PCs (and many other silicon-based electronics). The ODMs developed such complete operations that some even created consumer-facing brands to sell PCs as a first party, in search of margins and revenue.

In a sense, the headquarters of an OEM was the business operation and the ODM the product and manufacturing arm, managed on metrics of cost, time to delivery, and quality. In this view, Windows itself became just another part of the supply chain, albeit the second most expensive part, usually far behind Intel. That’s why PCs tended to converge on similar designs. Some argued that the ODM process drove much of that with a small set of vendors looking to keep costs low and sourcing from a small set of suppliers to meet similar needs from US sales and marketing arms. Even though there were a dozen global PC makers, the increasing level of componentization and the ODM model caused a convergence, first with desktops and now we were seeing the same happen with laptops.

Effectively, ODMs were driving a level of commoditization. On the one hand, this was great for better device driver support and a more consistent Windows experience, as investments the ecosystem made were leveraged across independent PC makers. On the other hand, this led to margin compression for PC makers which put even more pressure on ODMs and Microsoft. Further, given all PC makers faced similar constraints, PCs tended to converge to an average product, rather than an innovative one. There were a few outliers such as Sony who continued to drive design wins, but with ever-decreasing volume (Sony sold off their PC business in 2014.)

Roanne and Bernardo were treating the ODMs with the same level of attention as OEMs, something that had not been done before. The PC business was extremely healthy in terms of unit volumes, but the OEMs were all struggling to maintain profit margins and were looking to ODMs for leverage. There was a great deal of envy of Apple and its sleek new MacBook laptops made from machined aluminum, but, more importantly, the margins Apple earned from those PCs were impressive. The OEMs were pressuring the ODMs to deliver the same build quality with room for ample margins and a lower price than Apple, which was believed to be charging premium prices at much lower volume. In manufacturing, volume is everything so it is reasonable to assume that much higher volume could make lower prices possible, but only if the volume was for a small number of different models which the OEMs were not committed to. The ODMs thought this was impossible and continued to push their ability to deliver higher-margin and higher-priced premium laptops.

Early in my time at Windows, I went to Asia to visit with some of the ODMs to see firsthand their perspective on the PC and the relationships across the ecosystem. Visiting with the ODMs brought these tension front and center and proved informative.

The ODMs that served multiple OEMs were quite stringent about secrecy and leaks across their own companies. Each OEM had distinct and secured facilities, and the ODM management structure was such that information was not shared across facilities. Visiting a single ODM meant seeing buildings for any one of the major global manufacturers all identical on the outside, but each entrance was guarded as though the building was owned and operated by the specific OEM. Access was closely guarded and employees of the ODM never crossed into different facilities. I recall once having an Apple building pointed to in a manner that reminded me of driving by a building on the Washington, DC Beltway when everyone knows it is a spy building, but just remains quiet and doesn’t say a word. An ODM even acknowledging they served Apple would jeopardize their business even though it was an open secret.

The ODMs themselves were struggling with margins, even though they benefitted from a highly favorable labor cost structure in Asia. Several were responsible for manufacturing Apple devices, and while they would certainly never, ever divulge any details about that process, we knew that much of the math they would show us, bleak as it was, was informed by what they were doing for Apple and other OEMs.

One of the larger ODMs that I also understood made Macintosh laptops—and was run by a founder and CEO who had grown the company from the 1980s—proved to be an adventure to visit.

I arrived for my tour and put on a bunny suit and booties, deposited any electronics and possessions into a safe, and entered through a metal detector. There were cameras everywhere. There were acres of stations on the floor of a massive assembly line, each one responsible for a step in the manufacturing process. Pallets of hard drives, motherboards, screens, and cases arrived in one end, and progressed through the enormous assembly line stopping at each station. One added the hard drive, while one was attached the screen. Another verified that everything powered up. The final assembly step was where they attached the Genuine Windows hologram that proved that the Windows software was not pirated and was purchased legally. The ODMs always made a point of showing me that step knowing their role in anti-piracy was something we were always on the lookout for. Then the machines were powered up and burned in for a few hours to make sure everything worked.

After seeing the line, we ventured to the top-floor of the building to the CEO’s private office, which was the entire floor. On this floor was a beautiful private art collection of ancient Chinese calligraphy and watercolors. After a ritual of tea and tour of the gallery, the discussions of business began.

Instead of hearing about all the requirements from Windows, the CEO raised many issues about our mutual customers. We discussed the constant squeeze for margin, the pressure to compete with Apple without paying Apple prices, and what I found most interesting: the desire for flexibility, which precluded everything else. The OEMs, it turned out, were born out of an era during which desktop PCs were made from a number of key peripherals, such as a hard drive, graphics card, memory, and other input/output cards. Each of these could be chosen and configured at time of purchase. This allowed for two crucial elements of the business. First, the customer had a build-to-order mindset, which was appealing and a huge part of the success of Dell. Second, the OEM could bid commodity suppliers of these components against each other and routinely swap out cheaper parts while maintaining the price for customers. This just-in-time manufacturing and flexible supply chain were all the rage in business schools.

The problem was that this method did not really work for laptops and especially did not work for competing with Apple. Apple designed every aspect of a laptop and chose all the components and points of consumer choice up front. This gave Apple laptops the huge advantage of being smaller and lighter while also not having to account for a variety of components placing different requirements on software, cooling, or battery life. This integrated engineering was almost the exact opposite of how the Windows PC makers were designing laptops.

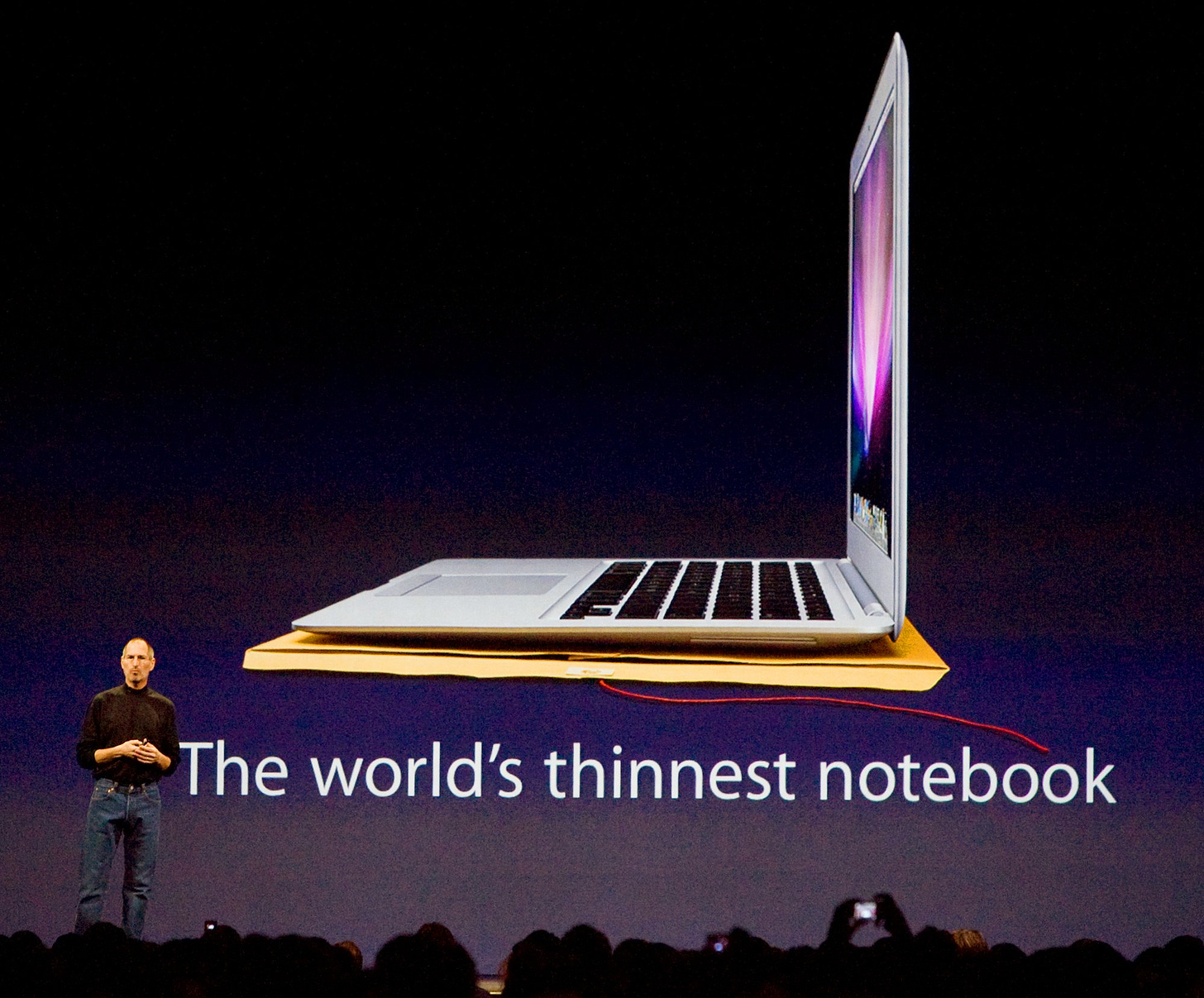

During one visit in 2008, after the MacBook Air had recently been released, it was all the ODMs could talk about. The only PCs that came close were made in Japan for the Japan market or achieved little critical mass in the US except among tech elites, such as the Sony VAIO PCG-505 or the Fujitsu LifeBook that I used. The Air’s relatively low(-ish) price point would eventually lead to an Intel marketing initiative called Ultrabook™ but as future sections will describe, it would be years before the PC ecosystem could respond to the Air.

From an ODM perspective, the requirements for the supply chain were driven by non-engineers or marketing from the OEMs back at HQ and seemed disconnected from the realities of manufacturing. They felt they had the capability to build much sleeker PCs than they were being asked. Always implied but never stated was the fact that some of them built devices for Apple.

Meeting after meeting, I heard stories of ODMs who knew how to build leading and competitive laptops but the US OEMs, even when shown production-ready prototypes, would not add them to their product lines. They wanted cheaper and more flexible. Or at least that was the frustration the ODMs expressed.

From a software perspective, I began to understand why PC laptops were like they were. For example, they were relatively larger than Apple laptops to enable component swapping as though they were desktops. Nearly every review of a Windows laptop bemoaned the quality of the trackpads—both the hardware and software—and here again the lack of focus on end-to-end, including a lack of unified software support from Windows and a requirement for multi-vendor support, made delivering a great customer experience nearly impossible. It was also the case for cellular modems, integrated cameras, Bluetooth, and more.

The desire for lower costs would preclude advanced engineering and innovation in cooling. This led to most Windows laptops to have relatively generic fans and overly generous case dimensions to guarantee airflow and cooling for a flexibility in componentry. The plastic cases filled with holes and grills were just the downstream effect of these upstream choices. So was the fan noise and hot wind blowing out the side of a Windows laptop.

Review after review said Windows laptops didn’t compare to the leading laptops from Apple, and yet I could see the potential to build them if only one of the OEMs would buy them. They simply didn’t see the business case. Their view was that the PC was an extremely price-sensitive market, and their margins were razor thin. They were right. Still, this did not satisfactorily explain Apple nor the inability to at least offer a well-made and competitive Windows PC. Though simply offering it would prove to be futile because of the price and limited distribution such a low-volume PC would necessarily command. We were caught in a bad feedback loop.

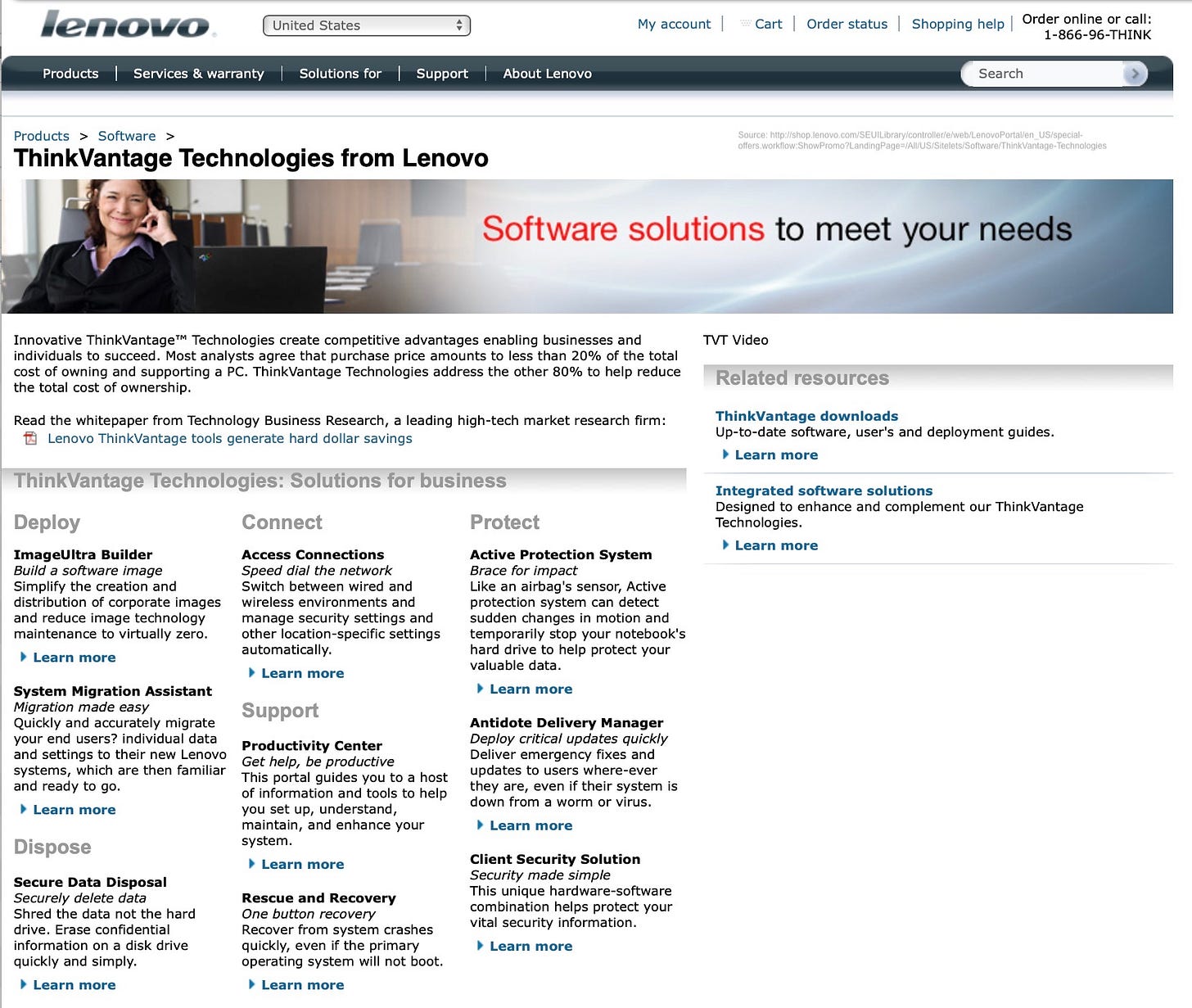

A larger initiative Roanne and team would take on was the infamous “crapware” issue, the phrase coined by Walt Mossberg years earlier. Tech enthusiasts and also reviewers tend to view crapware through that namesake lens as software that just makes the PC worse. OEMs had a decidedly different view and to be honest one that as I learned about it, I worked hard to be more sympathetic to. To the OEMs, additional software was a means of differentiation and a way to make their own hardware shine. We tended to think of crapware as trial versions of random programs or antivirus software, but to the OEMs this was a carefully curated set of products they devoted enormous resources to offering. While some were trials and services designed to have revenue upside, others were developed in-house and were there because of unique hardware needs. The grandest example came with Lenovo ThinkPads called ThinkVantage Technologies or TVT.3 Under this umbrella the full enterprise management and control of the PC hardware was enabled by Lenovo. While I might have an opinion on quality or utility, there was no doubt they were putting a good deal of effort into this work and most of the features were not part of Windows.

Previously I described the OEM relationship as adversarial. That might have been an understatement. The tension with OEMs was rooted in a desire to customize Windows so that it was unique for each OEM or each product line from an OEM. Microsoft’s view was these customizations usually involved “crapware” and that Windows needed to remain consistent for every user regardless of what kind of PC it ran on. It is easy to see this is unsolvable when framed this way. It was amazing considering how completely and utterly dependent Microsoft was on OEMs and OEMs were on Microsoft. This is a case where new people with a new set of eyes had a huge opportunity to reset the relationship.

What I just described was a few months of my own journey to understanding why PCs were like they were, and now I felt I understood. Because I was new, and we had a new team led by Mike, we were optimistic that we could improve the situation. There was no reason to doubt that we could. We believed we understood the issues, levers, and players. It seemed entirely doable. We just had to build trust.

The primary interaction with OEMs were “asks” followed by “request denied” which then led to a series of escalations and some compromise that made neither happy. This would be repeated dozens of times for each OEM for many of the same issues and some specific to an OEM. As with any dynamic where requests are denied, the result was an ever-increasing number of asks and within those an over-ask in the hopes of reaching some midpoint. If an OEM wanted to add four items to the Start Menu, then the ask might be to “customize every entry on the Start Menu” and a reply might come back as “none” or “no time to implement that” and then eventually some compromise. It was painful and non-productive.

There are two schools of thought on these issues. One is that it is obvious that Windows is a product sold by Microsoft and the OEMs should just pass it along as Microsoft intended it to be—relegating the OEM to a wholesale distributor. In fact, the contract to buy Windows from Microsoft specifically states that the product is sold a certain way that should remain. Given the investment OEMs made in building a PC, they did not see the situation that way at all.

The other is that it is equally obvious that the OEMs are paying Microsoft a huge amount of money and they own the customer relationship, including support, so they should be able to modify the product on behalf of their end-user customers. As it would turn out, the first view was on pretty firm ground, at least prior to the 1990s antitrust case. After settling that case, the conclusion was that the right to modify the product as an end-user would pass through to OEMs and Microsoft had limits in what it could require. (If people reading this are thinking about how Android works with phone makers today, you have stumbled upon the exact same issue.)

Perhaps using the word adversary as I have previously used was too blunt. In fact, the relationships were often far more complex and nuanced, fraught with combinations of aligned and mis-aligned incentives. It was entirely the case that the OEMs were our customers, but that was confusing relative to end-users who were certain they were buying a Microsoft product while also a PC maker’s product, and often the Microsoft brand was paramount in the eyes of consumers. The OEMs were also Microsoft partners in product development—we spent enormous sums of money, time, and resources to co-develop technologies and the whole product—yet this partnership felt somewhat one-way to both sides. OEMs were often viewed as competitors as they ventured into Linux desktops and servers, while at the same time they viewed Microsoft as offering one of several choices they had for operating systems. We certainly viewed OEMs as the source our shortcomings relative to Apple hardware, yet the OEMs viewed us as not delivering on software to compete with Apple. Even as distribution partners, depending on who was asked, the OEMs were distributors of Windows or Windows was a distribution tool for the PC itself.

These dysfunctions or as most schooled in how the technology stack evolved referred to them as “natural tensions” had been there for years. There’s little doubt that the antitrust settlement essentially formalized or even froze the relationship, making progress on any part a challenge. There was no doubt a looming threat of further scrutiny as the ongoing settlement-mandated oversight body remained. I met regularly with the “Technical Committee” and heard immediately of anything that might be concerning. Every single issue was resolved, and frankly most trivially so, but the path to escalate was always there.

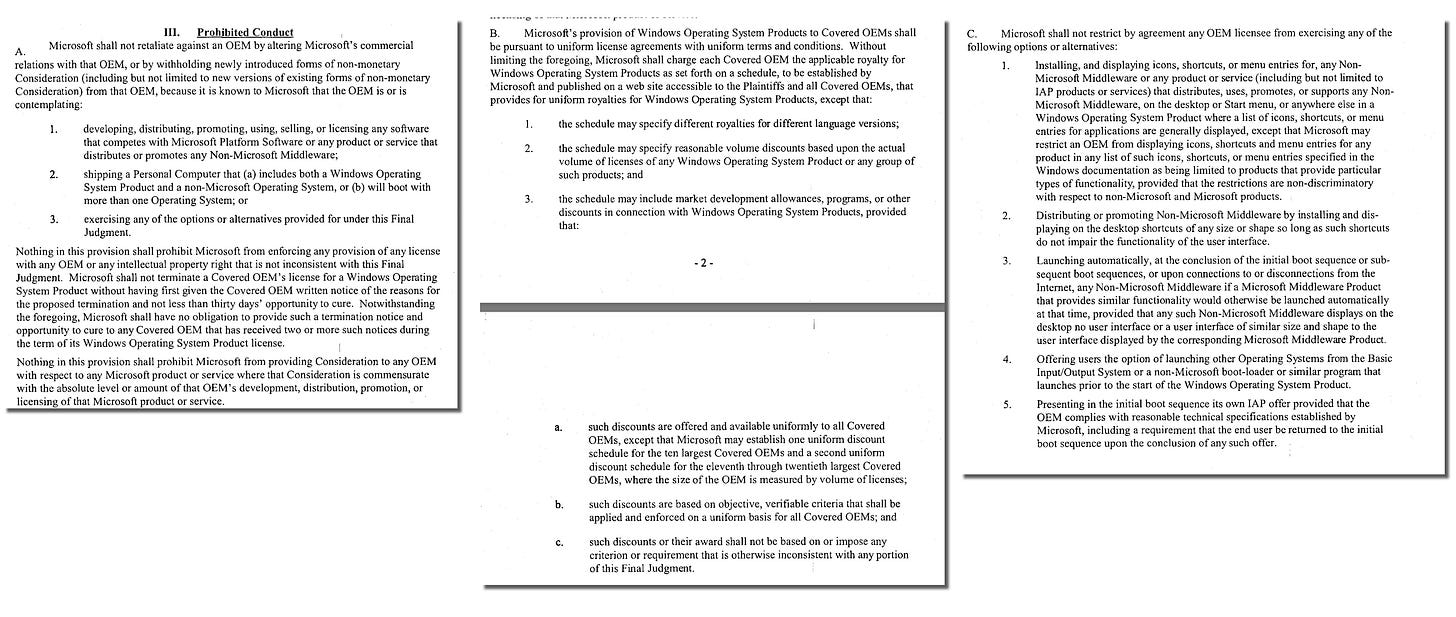

At the conclusion of the antitrust case, the Final Judgement or Consent Decree (CD) formalized a number of aspects of the relationship, some surprisingly made it more difficult to produce good computers and others simply reduced the flexibility the collective ecosystem had to introduce more competitive or profitable products. While the CD was generally believed to focus on the distribution of web browsers and Java (or in other markets, media players and messaging applications) it also dictated many of the terms of the business licensing relationship. Many of these related to the terms and conditions of how Windows could be configured by OEMs, essentially extending the OEM rights beyond simply installing competitive browsers to just about any software deemed “middleware” as Java was viewed.

In terms of bringing Windows PCs to market, the CD had three main sections:

Non-retaliation. The first element was that Microsoft could not retaliate against OEMs for shipping software (or middleware) that competes with Microsoft, including shipping computers running competitive operating systems. This codified the right of OEMs to ship Linux and even dual-boot with Windows for example. My how the world has changed, now that is a feature from Microsoft!

Uniform license terms. Basically, this term meant all OEMs were to be offered the same license and the same terms. Historically, as most all businesses see with high-volume customers, there were all sorts of discounts and marketing programs that encouraged certain behaviors or discouraged others. Now these offers had to be the same for all OEMs (for the top 10 there could be one set and then another for everyone else). In many ways, the largest OEMs got what they wanted but not since this put the best customer on the same playing field as the tenth best. This did not preclude the ongoing Windows Logo program described below.

OEM rights. The CD specifically permitted a series of actions the OEMs could take with regard to Windows including “Installing, and displaying icons, shortcuts, or menu entries for, any Non-Microsoft Middleware or any product or service” and “Launching automatically, at the conclusion of the initial boot sequence or subsequent boot sequences, or upon connections to or disconnections from the Internet, any Non-Microsoft Middleware.” These terms, and others, got to the heart of many of the tensions with OEMs over “crapware” or software that many consumers, especially techies, complained about. Now, however, it was a right OEMs had and Microsoft could do little to enforce that.

There were many other terms of course. Since we were “stuck” with each other, with Windows 7 we tried a nearly complete reset of the OEM relationship.

The bulk of this work was captured in the Windows logo program—these were the instructions from Microsoft for how OEMs installed and configured Windows during manufacturing described in the OEM Preinstallation Kit (OPK) authored by Microsoft with ample compliance scrutiny. Given the above, one could imagine that most anything was permitted. However, Microsoft retained the rights to implement a discount program for strictly adhering to a set of constraints to earn the “Designed for” logo. Sometimes these were discounts and other times marketing dollars for demand generation, though these are equivalent and interchangeable pricing actions by and large.

We viewed these constraints as setting up a PC to be better for consumers. OEMs might agree, but they also saw them as hoops to jump through in order to get the discount, which their margins essentially required. These logo requirements ran the gamut from basics like signing device drivers and distributing available service packs and patches to how much to configure the Start Menu. None of them ever violated the CD as per ongoing oversight. It was these aspects of Vista that were particularly adversarial.

We revisited all the terms and conditions in the OEM license (and logo) and worked to make the entire approach more civil. We wanted OEMs to have more points of customization while also building the product to more robustly handle those customizations—we aimed to reduce the surface area where OEMs could fracture the Windows experience. We also would spend a lot of energy making the case for why not changing things would be a good idea and in favor of lower support costs or more satisfied customers. A key change we made from the previous structure was to have the same team responsible for taking feedback and producing the logo requirements. This eliminated the organizational seam as well as a place for OEMs to see potential conflicts across Microsoft, and exploit those.

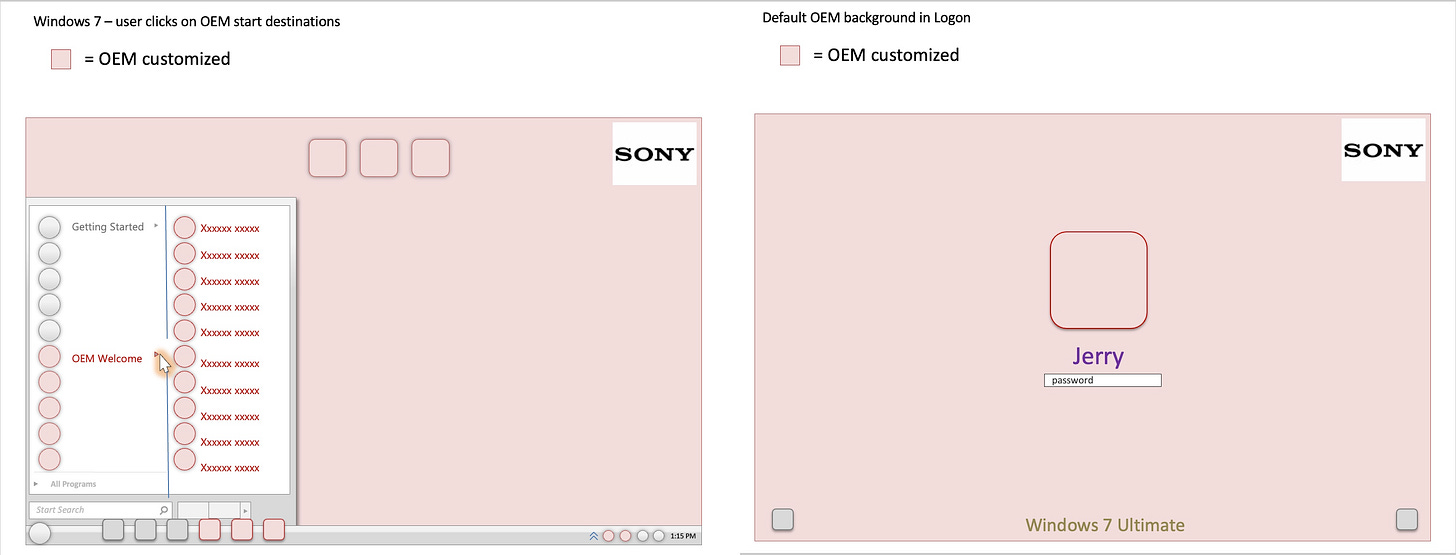

As an example, early in the process of building Windows 7 Roanne and team would present to the OEMs examples of where they were given rights (and technical capabilities) to customize the out of box experience (OOBE) when customers first experienced a new PC. In one iteration we showed a color-coded screens where the OEM customizable region was clearly marked indicating just how much of Windows was open to OEM customization. This type of effort was a huge hit.

The process of collaborating with the OEMs was modeled after our very early Office Advisory Council (OAC) that was run out of the same product planning group where MikeAng and Roanne were previously. Instead of just endless slide decks that spoke at the OEMs, we engaged in a participatory design process with the OEMs, a planning process. We listened instead of talked. We gathered feedback. Then we answered their specific questions.

We began the process of working with the OEMs just as we completed the Vision for Windows 7. We did that because by then we had a real grasp of what we would deliver and when, and at least what we said was rooted in a full execution plan. This was decidedly different than past engagements where the meetings with OEMs reflected the historic Windows development process, which meant that much of what was said at any given time could change in both features and timing. For the OEMs with very tight manufacturing schedules and thin margins, information that was so unreliable was extremely costly to them. At every interaction they had to take the information and decide to act on it, allocate resources, prioritize a project, and more, taking on the risk that the effort would be wasted. Or they could choose to delay acting on some information, only to find out it was critical to start work to provide feedback that might be significant. It was a mess.

What Microsoft had not really internalized was just how much churn and the level of real dollars it cost the OEMs with this traditional interaction. In fact, most involved on the Microsoft side felt, as I would learn, quite good about the openness and information being shared. I learned this both from the OEM sales team and directly from the CEOs of OEMs who were starting to get rather uncomfortable with the lack of information. They began to get nervous over my lack of communication (literally me and not the OEM team) as I had not provided details of the next release even after being on the job for months. I just didn’t know the answers yet. Our desire to be calm and rational created a gap in communication that worried people. It was not normal. We had not set expectations and even if we had it wasn’t clear they would have believed us.

MikeAng characterized the old interaction as “telling the OEMs what we were thinking” when we needed to be “telling OEMs what we were doing.” By characterizing what we were going to improve this way we were able to avoid massive amounts of wasted effort and negative feelings. We also believed we would reduce the number of budget-like games when it came to requests. No matter how much Microsoft might caveat a presentation as “early thoughts” or “brainstorming,” customers looking to make their own plans under a deadline will hear thoughts as varying degrees of plans. Only later when those plans fail to materialize does the gap between expectations and reality widen—the true origin of dissatisfaction. At that point the ability to remind a customer of whatever disclaimer was used is of little value. The customer was disappointed. This cycle repeated multiple times over the 5-year Vista product cycle, and many before that over the years.

With the Windows 7 vision in place, we began a series of OEM forums and meeting at least every month with each OEM. Each forum (an in-person workshop style meeting) would focus on different parts of the product vision or details about bringing Windows 7 to market. Roanne and team dutifully documented the feedback and interactions. We actively solicited feedback on priorities and reactions to the product overall. Then we summarized that work and sent out summary of engagement memos to the OEMs. In effect, the relationship was far more systematic, and the information provided was far more actionable. From the very start we communicated a ship date for the product and milestones, and a great deal of information about the development process. We reinforced our attention to the schedule with updates and information along the journey.

The entire process was run in parallel for the key hardware makers: storage, display, networking, and so on. We also repeated it for the ODMs. The team did an amazing job in a very short time, for the first time.

Over the coming months and really years, the reestablishing of trust and the effort to become a much more reliable, predictable, and trustworthy partner would in many ways not only change this dynamic and experience for OEM customers, but significantly improve the outcome for PC buyers. At the same time, OEMs were able to see improvements in satisfaction and potential avenues to improve the business. The PC would see many major architectural changes over the course of building Windows 7—the introduction of ink and touch panels, broad use of security chips and fingerprint login, addition of sensors, expansion of Bluetooth, transition to HDMI and multiple monitors, high-resolution panel displays, ever-increasing use of solid-state disks, and the transition to 64-bits. The Ecosystem team would be the conduit and moderating force between OEMs, their engineering teams, the engineering teams on Windows, and even Microsoft’s own OEM sales and support team.

The Windows business faced a lack of trust from every business partner. The Windows team needed to move from chaotic process that promised too much and delivered inconsistently and late. Instead, we aspired to make bold but reliable promises—my guiding principle, the mantra of promise and deliver. While we talked big, the ball was in our court. We put in place a smoother and more productive engagement with OEMs. Throughout the course of developing Windows 7 and beyond, we consistently measured the success of the engagement with qualitative and quantitative surveys. Through that we could track the ongoing improvement in the relationships.

Promise and deliver.

Just as we worked to gain renewed focus with OEMs, Apple chose to declare war with Microsoft, and the PC, with clever and painfully true primetime television commercials. While the commercials began before Vista, the release and subsequent reception of Vista were exactly the material the writers needed for the campaign to take off.

On to 090. I’m A Mac

https://www.wired.com/2007/07/acer-president-the-whole-industry-is-disappointed-with-windows-vista/

https://www.neowin.net/news/bill-gates-hardware-to-be-nearly-free-in-10-years/

http://shop.lenovo.com/SEUILibrary/controller/e/web/LenovoPortal/en_US/special-offers.workflow:ShowPromo?LandingPage=/All/US/Sitelets/Software/ThinkVantage-Technologies (via archive)

thank you for sharing these stories! minor nit (since i assume this all ends up in a book at some point): disparegenly should be disparagingly i think?

I joined the team that became PC3 from Dell just before the launch of Vista, so I would love to hear about your relationship with Bill Mitchell and our role with the OEMs. I know that relationship was, shall we say “contentious”?