060. ILOVEYOU

"Love You computer worm affects two-thirds of Fortune 500 companies…causing what some analysts estimate to be billions of dollars in lost productivity." —CNN May 2000

Viruses were nothing new in the late twentieth century, but we were about to cross a line where they were far more than annoyances. This is the story leading up to and crossing that line and the very difficult decisions we had to make relative to the value propositions in our products and that customers appreciated. It sounds easy today, but at the time it was enormously difficult. Breaking your own code is never a trivial matter. This story is also a bit of a sleuthing adventure as tracking down this virus is an important part of understanding the dynamics and context of making difficult changes—there’s always a conspiracy theory. We will follow the story through John Markoff’s excellent NY Times reporting, which was rather frustrating to me at the time.

It is somewhat odd to be writing about viruses for computers when we face such a tragic biological virus. At the same time, we are still unwinding from an incredible zero-day exploit so the lessons herein seem quite relevant as well.

This post, slightly edited, appeared as an excerpt in Fast Company in May 2020, on the 20th anniversary of ILOVEYOU with a related Q&A Steven Sinofsky lived Microsoft history. Now he’s writing it. Many thanks to Harry McCracken (@harrymccracken), global technology editor at Fast Company.

Back to 059. Scaling…Everything

One morning during the first week of May of the new millennium, I received a call at my apartment while I was getting ready for work. I heard a reporter tell me their name, and then listened to hyperventilating and (apparently) proclaiming their love for me repeatedly, “I love you. I love you.”

That’s what I heard, anyway. The call. A reporter. Early morning. It was all weird.

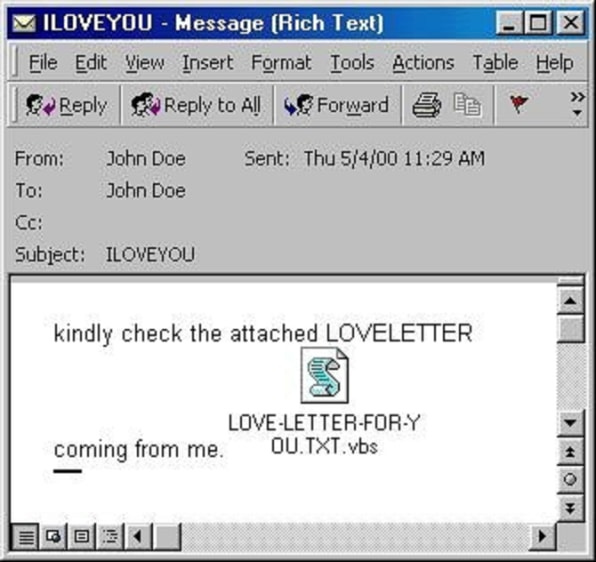

Unfortunately, LOVE broke out all over the internet. Over the span of a weekend, inboxes around the world of Outlook and Exchange email users were inundated with dozens of copies of email messages with the subject line, “ILOVEYOU.”

I learned from the reporter that the LOVE email incident was deemed so serious that the PR lead gave them my home number and simultaneously sent me a briefing via email. In the era of dial-up, I could not read the email and talk on the phone because I only had one analog phone line at home. I had no idea what was going on, so I agreed to return the call after I dialed up and downloaded my email.

That’s when I realized the magnitude of the issue.

For all the positives of the PC in business, IT professionals still wrestled with the freedom of PCs, not only the freedom to create presentations and spreadsheets but the freedom to potentially wreak havoc on networks of connected PCs because of computer viruses. Viruses were hardly new, part of PCs from the earliest days. As a new hire in the Apps Development College training, I completed a unit on early MS-DOS viruses. The combination of many more PCs in the workplace, networking, and then email created a new opportunity for those wishing to do harm with viruses. By their nature, and by analogy to the word virus, most viruses are not fatal to a PC, but they could cause significant damage, loss of time, and take a good deal of effort to clean up.

By the late 1990s even amongst government and academia, the risk posed by viruses to the nation’s infrastructure were front and center. Fred B. Schneider, a Cornell faculty member (and former sponsor of our chapter of Association of Computer Science Undergraduates), chaired a working committee going back to 1996 on the topic of trustworthy information systems (the word trustworthy will make an appearance in much of Microsoft’s reaction to the stories shared here). The committee included faculty from many universities and representatives from across industry, including Microsoft’s George Spix (GSpix). The work was convened by Computer Science and Technical Communications Board of the National Research Council whose members included Butler Lampson (BLampson), Jim Gray (Gray) and Ray Ozzie. The effort resulted in a 300-page report that was widely influential, once the commercial world caught up with these challenges.

Enterprise IT was increasingly uneasy about viruses and had the expectation that Microsoft must do something. The openness of the PC platform was a hallmark feature responsible for the utility and breadth of the PC ecosystem, even if some bad actors (as they were called) might exploit that openness. Microsoft took a laissez-faire approach to this annoyance.

Office shared this permissive attitude until the mid-1990s and the rise of networks when sharing files became common. With everyone connected, an annoyance morphed into a virus that shared itself automatically between computers. A virus infected Microsoft Word 6.0 called WM/Concept.A—viruses often had cryptic names. In this case the WM stood for Word Macro, and presumably Concept referred to the fact that this was testing a new concept for viruses.

This was a new type of virus. It did not exploit bugs or programming mistakes in Word. Concept used Word macros as they were designed. Macros were present in software for ages, going as far back to the MS-DOS days of WordPerfect and Lotus 1-2-3. Macros, called programmability or extensibility in Microsoft lingo, were a prized accomplishment and something BillG believed in pushing extensibility for all products. Programmability made a product sticky when customers invested time and effort to write macros. Macros were used to automate repetitive tasks, for example, if a company wrote similar letters to customers for past due notices, one could write a macro, which generated letters with all the right address fields and salutations. Another example might be to automate collecting sources in a document and creating a bibliography. The uses for macros were endless and an entire industry developed consulting and training in Word automation. Word macros used a derivative of BASIC.

Some macros were written to automatically run as soon as a file was opened, making systems appear more automatic to end-users. The WM/Concept.A virus took advantage of a combination of features to create an exceedingly simple and yet maximally annoying experience including: macros, automatic start-up, and networked file sharing.

The original author of WM/Concept.A probably crafted a tantalizing document with the virus and shared it on a network knowing others would open the document, sort of a patient zero. Once anyone opened that document, every document they created or opened became infected. Any document they shared became infected and infected every PC that opened that document. Like the old shampoo commercial, “ . . . and they told two friends, and they told two friends, and so on, and so on.” Well, that is exactly what happened. WM/Concept.A circled the globe relentlessly.

Contrary to what was commonly believed, successful viruses didn’t usually do anything harmful like delete all your files or format your hard drive. If they did, the viruses failed to spread and serve their purpose. WM/Concept.A did only one annoying thing other than propagate, and that was to display a message that looked like a broken Word error message—a simple window with the character “1” and button labeled “OK.” That was it. The message showed up once during the initial infection.

While there was no direct harm to PCs or any documents, the obvious implications of this Concept virus were that viruses could easily spread and, if the author wished, could do significant harm or at the very least truly interrupt workflow, and at most, do heinous things like delete text at random times or worse. Removing WM/Concept.A from an infected system was a chore. A cottage industry of virus removal and disinfecting was born, as was a cottage industry of using the Concept techniques to do more harm.

With this virus, General Manager of Word, PPathe (Blue), decided to take the first steps on Microsoft’s antivirus crusade. Blue and team changed the way macros worked. They added a warning noting that a document contained a macro installed, and also made it more difficult to run macros automatically when simply opening documents. These were small steps and were, in spite of the awfulness of WM/Concept.A, greeted with much pushback by fans of Word and IT managers because these changes broke business systems and workflows. Blue stood his ground and Microsoft’s PSS team proactively worked with customers to get the word out, so to speak.

WM/Concept.A was our first lesson in the incredible balance between building an extensible and customizable system and the need to maintain security and reliability on PCs, and how customers push back when making products more secure means making changes in how they work. But the virus scared me in a much broader way. I wrote another frantic twenty-page memo, Unsafe at Any Megahertz. The title was a reference to the Ralph Nader book that shook up the auto industry in the 60s. It was meant to be a call to action for our product engineering. The software industry grew up from the counter-culture 1960’s. Steve Jobs wore no shoes. Bill Gates hacked his high school computer system. Both were college drop-out. What the PC industry lacked was any formal notion of what it meant to be a software engineer. My clarion call was that our lack of formalism, reproducibility, and external validation would only result in heavy-handed government regulation. I pondered a sort-of Underwriters Laboratory for software. That would be scary. I never sent the memo for fear it would be viewed as just too controversial in a company and industry that was the epitome of informal. Instead, the memo was a good exercise for me in writing is thinking and it made me double-down on how Office would operate with respect to product quality.

The ability for bad actors or even pranksters to wreak havoc on the growing and newly connected PC infrastructure became a major liability for Microsoft. Yet our products were behaving exactly as designed and customers appreciated those design patterns—extensibility was a major selling point of Office and a major part of our product and engineering efforts. As soon as we introduced the functionality changes, new viruses were created that circumvented what protections were in place.

While in the midst of creating the vision for Office10 in early 1999, our PR firm, Waggener Edstrom (often called WaggEd), received an inbound request from John Markoff of the New York Times. Markoff was one of the most respected reporters in technology with a deep history in reporting on all aspects of the industry, especially on intensely technical topics. He received broad acclaim for two books on hacker culture and in particular the effort that led to the identification and capture of Kevin Mitnick, who was convicted of several computer-related crimes.

In our case, Markoff inquired about a feature in Office 97, Office 2000, and a related feature in Windows 98. He was following a tip he received, which we later learned was from a programmer, well known to Microsoft, who built tools for MS-DOS. He was told that documents created with those versions of Office seemed to have been stamped with what the tipster referred to as a “digital fingerprint.” Related to this, it appeared as though the programmer discovered that Windows 98 was also creating what amounted to a fingerprint for an entire PC using similar technology. The combination meant both documents and PCs seemed to have fingerprints.

Kim Bouic (w-kimb, now Barsi) of Waggener Edstrom called me right away. Kim was the PR executive leading the Office business and was exceptional at handling crisis situations like this. On the one hand, she talked me down from lecturing reporters about how they didn’t understand, and on the other gently reminded reporters that things might be more complex than they seemed. Her skills were needed more than ever as “digital fingerprint” was rapidly becoming a crisis.

Markoff was chasing two lines of inquiry and they were leading to the same conclusion, which was that Microsoft created some sort of fingerprint or serial number in Windows and Office—if so, this constituted a major risk to privacy because documents and computers could be traced using this technology. As if this weren’t enough, Intel announced the new Pentium III chip and it contained a unique serial number, which Intel said was for security use but fed right into the narrative of serial numbers for tracking PCs. To make this all the more ominous, in one of the early discussions with Markoff on Windows someone referred to the technology as a GUID (pronounced goo-id), an acronym for globally unique identifier.

Big Brother was suddenly part of the story.

GUID was the name of the Windows functionality that did, in fact, create what was intended to be a unique number—something useful for a broad range of programming tasks. The origins of Microsoft GUIDs were buried deep within the system but the value of a number that was for all practical purposes unique beat people trying to create a number on their own, something that eluded computer scientists for years—in fact, the origins of GUIDs went back at least to early 1980s Open Software Foundation work and were originally called UUIDs, for universally unique identifiers. To create the unique number, the GUID creation function combined several pieces of information. One of them was the serial number of a network card called the MAC address, which was relatively unique and required for networking. That serial number remained visible in the GUID. So, someone with a GUID and access somehow to serial numbers of network cards could identify a computer. The fact that there was no database of MAC addresses or even that anyone kept track of them, or that MAC addresses were part of the lowest level of how the internet worked, were all facts lost in the moment. Much to Kim’s frustration, I continued to try to explain.

Pro tip: If in a PR crisis you find yourself explaining some deeply technical thing, stop.

I could not stop. Kim was annoyed.

The specifics of how Microsoft ended up using GUID technology made this look bad, and that was what Markoff was on to.

This conspiracy theory ran deep.

In Office 97 we introduced hyperlinks as a native feature inside documents. It was part of our push to make Office great for the web. From within any Office document, clicking a link opened the browser. We were especially interested in links between Office documents on a web server. One problem with Office documents is that if files are renamed or moved then the link breaks. The WWW was already well known for broken links. In the corporate world, with reorgs and project name changes, files moved around a lot. We decided that by using FrontPage on the server we could keep track of links used in Office documents and detect when a file was moved, and then repair the links. We thought this was a great way to prevent what was becoming a huge web problem of broken links. We needed something more than a file name, since in a company files might frequently have the same name. A clever idea was to use the new feature of Windows to create GUIDs, and when a link was created to a document a GUID was also recorded. Links in HTML used the file and folder name, so if the file was moved or renamed the link broke. Having a GUID also gave us a chance to fix the link and find the file using FrontPage server. We thought this was a useful and solid plan.

Will Kennedy (WillK) was the development manager on the feature in Office 97, though he moved to Outlook shortly after we began Office10. An Alabama native, college hire, standing 6-foot, 6-inches tall, Will was the epitome of a calm development manager. I forwarded him some of the mail from Markoff describing the feature. He walked through all the Office code with the test team and ascertained we did store the GUID in a document (to further the conspiracy, the GUID was not visible to end-users in any way and was hidden in the file). However, as Office 97 progressed, albeit late, we never implemented the fix-up feature but the GUIDs remained. That seemed benign at the time. Will said it was trivial to remove the code that wrote the GUID to files. He prepared a quick fix for Office 97.

Simultaneously, but coincidentally, Windows 98 implemented a product registration tool that, in the process of registering the PC, collected a set of information about the hardware (how much memory, disk space, CPU, etc.). It was also optionally collecting personal information like any registration process. At Microsoft, the hardware information went to the development team and the optional personal information went to marketing’s customer database. As it turned out, the bits of hardware information needed a unique identifier. Windows chose to use a GUID.

GUIDs contained that network MAC number, which could link the Windows 98 registration and documents created with Office, no matter where those documents ended up being distributed.

The tipster, and Markoff, came up with a scenario by which Microsoft could, if it wanted, maintain the capability of knowing if a document was created on a PC and who registered that PC. In fact, the theory implied that given a random document, it might be possible for Microsoft to determine who created it.

All Microsoft needed to do was connect each of the new databases, and no one could stop us.

Kim needed me to get on the phone with Markoff and explain this theory away. I told her the theory was baseless, and therefore harmless, plus, we would never do what was being suggested.

But it was a conspiracy theory and those can’t be explained away.

Microsoft at the time (early 1999) was not exactly the most loved company and certainly not the most trusted, especially by those outside of technology. Combined with a lack of trust was a perception of power that rivaled governments.

On the other hand, the idea that somehow the Windows and Office teams could connect their databases and execute this scenario seemed laughable to me. We had enough difficulty connecting our bug databases and sharing code, even though we fully understood and had a use for those things!

Kim scheduled a call with Markoff. She reminded me once again to take Markoff seriously, and that I could not dismiss his concerns no matter how wild they were. On the call, I walked through the feature in Office, but there was no way to deny what Markoff was asserting. Microsoft did have these databases. There was a serial number of a network card in a GUID. Files had GUIDs. The story was ultimately filed and was, according to Kim, factual and accurate. As was almost always the case, I took the story personally. Kim reminded me that it was a win, considering where the story started and where it could have gone.

We issued patches to Office. We changed Office so that it did not create GUIDs (that we never used) and we also released a tool to remove GUIDs from existing documents. Windows also changed the product registration tool and the way the GUID creation capability worked. GUIDs are widely used today on the internet in browsers, websites, and mobile phones in almost every application.

The GUID story was also the introduction of the word metadata to the general public, data about data, not generally seen by end-users, but used to describe data. The GUID in an Office document was an example of metadata. With the rise of web browsing, web browser cookies, and mobile phone records, public awareness was just being raised. Privacy advocates were in force challenging metadata collection and analysis. We were truly entering a new era of privacy.

Whereas WM/Concept.A was the Office team’s first experience in dealing with networked viruses, GUID was our first experience dealing with privacy. These both came as we were planning Office10 and changed the way we thought about security and privacy. In fact, security and privacy moved from defensive capabilities to main tenets in our product vision.

We weren’t finished learning.

Just a few days after the New York Times ran Markoff’s story on GUIDs, I received an interesting message in Outlook with the subject line “Important Message from Jon.” And another interesting message with the subject line “Important Message from EJ.” And another. And another. In fact, my inbox was filled with “Important Message from . . .” messages.

That was no good.

Each message contained only the text:

Here is that document you asked for...don't show anyone else ;-)

and a file attachment called LIST.DOC.

I wasn’t the only person getting these emails. It felt as though everyone with Office running Outlook was receiving them, seemingly at the same time.

Then, suddenly, I received no more messages. I couldn’t send messages either. Email was down.

Microsoft shut down email service as did companies and email providers around the world. The internet was under attack by a virus, a replicating email virus. This virus was quickly analyzed by many across the internet—it was named W97M.Melissa.A as it left a signature containing the name Melissa on an infected PC. Melissa was a Word macro virus much like WM/Concept.A but one extended to use Outlook in order to replicate.

Office had been weaponized. This virus also did not harm the infected PCs but was generating so much email that servers were getting gummed up in what is called a denial of service attack, or DoS. The system administrators in charge of mail servers were angry. More importantly, for the first time perhaps hundreds of thousands or millions of white-collar workers were without email all at once, heading into a Monday morning of a work week.

If there had been any doubt, we immediately learned how important email was to the workplace.

Our customers and offices around the world were angry.

News reports were everywhere (though reporters resorted to phone calls to report) and the number of mail servers impacted was in the tens of thousands, which was hundreds of thousands if not more PCs. This was huge.

What was going on? This was a new type of virus. It introduced the term worm to the general population, named such because it could automatically spread itself to other PC users without any action, worming its way around the internet. In the press the terms worm and virus were used interchangeably. Once released into the wild via a deliberate simple email, Melissa virus spread when a recipient opened the file attached to the “Important Messages.” The message was designed to look familiar and so the file was almost always opened.

That was social engineering.

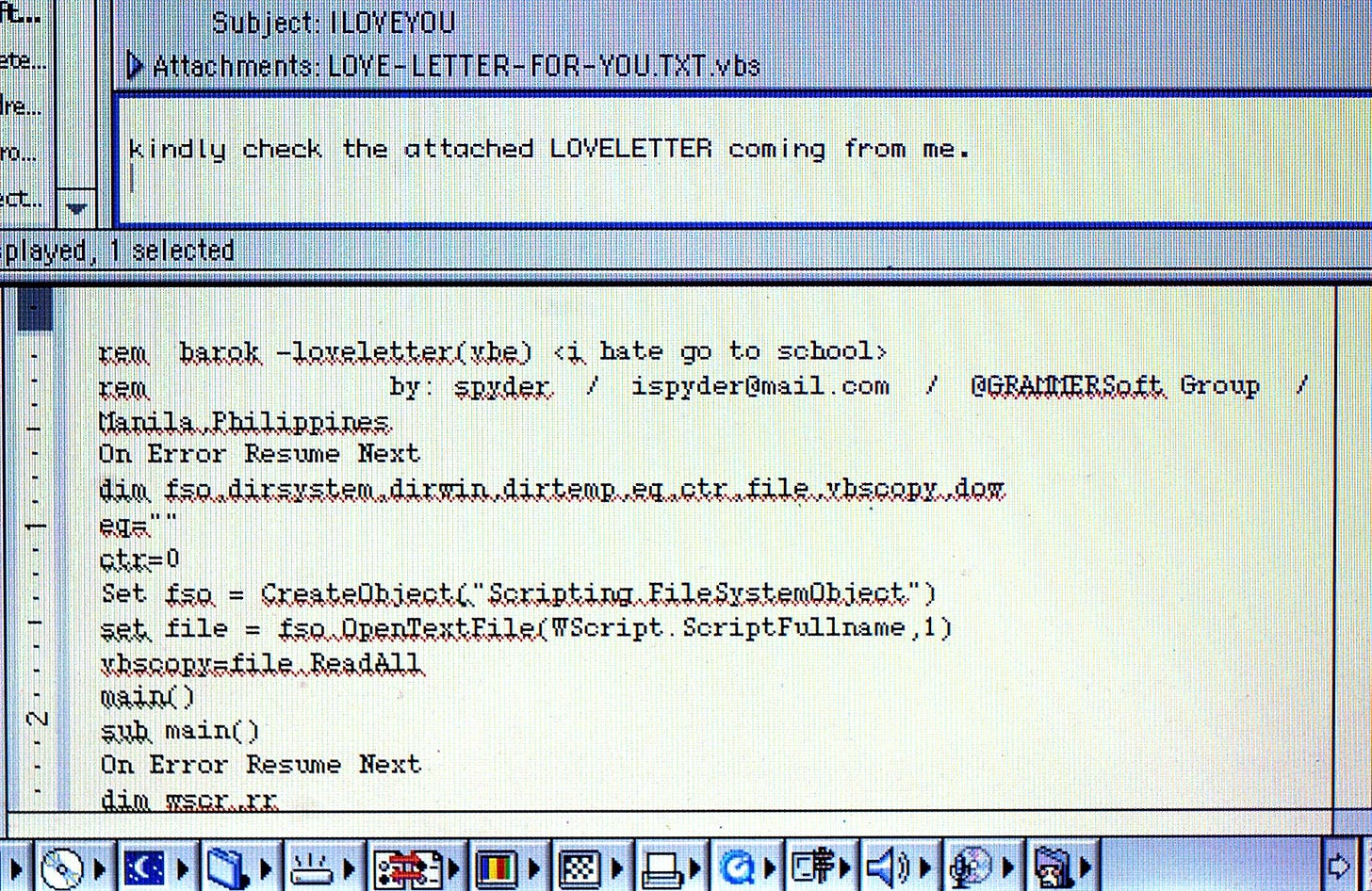

The attachment contained a Word macro and was written in a way that not only bypassed any protections added to Word after WM/Concept.A but immediately disabled the macro protection features. In this sense, it was the same as the Concept. When using any mail program but Outlook, Melissa was like Concept both in how it spread and its annoyance level (high).

If a user was running Outlook, then Melissa went one step further. The code in the Melissa virus used the macro capabilities of Outlook—yes, Outlook had those too, and customers really loved them—to automatically send the same “Important Message” to the first 50 people in the Outlook address book. Instead of telling “two friends,” each infected PC was telling 50 and each of those who opened the attachment told 50 more. That’s how the virus spread across the whole planet in a weekend.

If there was any humor to it (there was not), after mailing 50 people the virus, the code checked if the current day of the month was the same as the minute. If by chance it was, it added the following text to the currently open Word: “Twenty-two points, plus triple-word-score, plus fifty points for using all my letters. Game’s over. I’m outta here.” This made no sense until there was a deep dive into where Windows kept program settings (called the registry) where it recorded that Melissa infected the PC. There, text could be found reading “Kwyjibo.” Together those were a reference to an episode of The Simpsons, “Bart the Genius,” where Bart tries to cheat at Scrabble with that word.

Hunting down the propagators of viruses and worms was an internet hobby and a profession going as far back as Robert Morris and the infamous worm unleashed from Cornell in 1988 (while I was there for my first homecoming!) and sleuthed and then documented by Clifford Stoll in the incredible book, The Cuckoo’s Egg: Tracking a Spy Through the Maze of Computer Espionage. Immediately the internet tried to find clues to the origin of Melissa. In some ways this was similar to the Centers for Disease Control trying to find patient zero. With email this was possible because of the accurate time stamps and journey information in every message—the digital DNA of a computer virus.

Melissa offered up one other clue, unbeknownst to its creator. The LIST.DOC file had a GUID, the kind John Markoff wrote about (the same feature that we had just removed from Office). The tipster assisting Markoff, who we then knew to be Richard Smith, the CEO of Phar Lap, found the GUID and posted it online with the virus code. A graduate student in Sweden said the code looked familiar and pointed Smith to a user named VicodenES. Smith then began to connect the network card address (the same one he complained about as part of a GUID) and records of internet servers. Eventually, Smith was able to connect the whole trail of network card addresses to the actual creator of the virus. He was arrested in New Jersey at his parent’s home a week after releasing the virus.

The metadata in Office 2000 made that possible.

I wish I made that up.

We assisted IT managers and sysadmins in getting their systems back online and removing the virus. This was a criminal investigation, and for the Office team this was the first time we were involved in one at this scale and in real time. The week was filled with remorse, grief, anger, and finally, when we heard that metadata was involved in finding the criminal, pure disbelief.

The macro capability of Outlook, as used by Melissa, developed a huge following and was a strategic aspect of the product. We were in the same spot as we were a few years earlier with Word—a key feature enterprises valued was being weaponized by virus creators. For Word, we added a series of warnings and administrative controls. Our first steps in dealing with Melissa did the same.

As soon as we implemented these and put out updates, we heard from enterprise customers and the community of consultants, authors, and the Microsoft Most Valued Professionals (the group selected by Microsoft’s support professionals to represent the broad external community). We “broke” their solutions built on top of Outlook. Whether these were time management, scheduling assistants, customer relationship management tools for salespeople, or email automation (to name a few), the user was prompted by Outlook every time macros ran. It was annoying, but it needed to be that way because we did not have another readily available solution.

When people using software are in a flow going through some task such as from opening email, to booking tickets, to opening a program, to browsing web pages any warning messages that pop up are essentially ignored, and therefore meaningless.

This lesson was learned repeatedly by every generation of software. A warning message simply got in the way. No one reads text when there is an OK button right there.

As with Word, there was a gradual chipping away of the extensibility of Office. Our products (and customers) were put at risk due to an increasingly connected world. The design approaches we took that worked fine for tech enthusiasts no longer worked for typical office workers with relatively limited knowledge of the inner workings of PCs, and especially not for the administrators who supported them.

Once a virus is thwarted by any means, the community of bad actors works to find similar patterns to exploit, but ones that work around the fixes. In the meantime, an even larger community of copycats duplicate the existing exploit and take advantage of unpatched software or software protected by relatively unsophisticated antivirus tools that did not pick up on small changes to the pattern used. That’s how viruses work.

We briefly secured the product.

The press in the first week in May 2000 when I received that exhilarating call at home on Sunday morning were reporting billions of dollars in damage, computer users around the world blocked from using email or even working. The reports cited the previous Melissa exploit and the much earlier Concept virus in Word, and many in-between.

That’s when I realized the magnitude of the issue.

In reporting, once there are three points of evidence then there is a trend. In this case, the trend was the escalating risk of using Office and the escalating costs to business IT professionals maintaining corporate desktops—TCO, our old friend total cost of ownership, was again a critical issue.

In an online story posted the first evening of the spread, industry “experts” anticipated that by morning half of all PCs in North America became infected and more than 100,000 mail servers in Europe were infected or taken offline as a precaution. The United States Senate was infected, as were important news outlets such as Dow Jones. The infections reached worldwide telecom and television outlets in Denmark and employees of Compaq Computer as far away as Malaysia.

The impact was profound. Billions of dollars in immediate lost productivity and money spent to eradicate the virus. Customers were livid. If and how we responded to this was clearly going to be a test of the empathy for the pain customers were experiencing.

The creators of the ILOVEYOU worm, dubbed “Love Bug” in the widespread press, exploited a hole in the warning messages that ran when Outlook’s data (such as contacts) was accessed. As with Melissa, the worm used the contact list and replicated itself, but instead of just the first 50 contacts it automatically (and silently) sent mail to all the contacts in an address book. This infection also installed itself on the computer so it continued to run all the time and did damage by deleting files and replacing them with copies of the virus. The infection was started by an email attachment with the name “Love Letter,” which was a hidden program and not a letter at all. Any email program would have been vulnerable to this method of transmission, which simply required the user to open the file on their PC, but Outlook was not only the most prominent, it was also the most easily programmable.

It was bad. Really bad.

The team was trying to figure out what to do and began exploring options.

Microsoft Office was having a Tylenol moment. While the human suffering of the computer virus was dramatically less than that of the 1982 product tampering that left seven people dead from poisoning, the brand suffering was comparable. Could Outlook be trusted? Could Microsoft? Tylenol’s parent company, Johnson & Johnson, took unprecedented and drastic measures to save lives and rebuild consumer confidence in the brand. They removed all medicine from distribution and encouraged the destruction of all pills. In addition, the company diagnosed and improved their systems, including the development of tamper-resistant packaging. In doing so, they developed the modern playbook for crisis management.

Acting with uncharacteristic haste, the US Congress House Science Committee, Technology Subcommittee held hearings on May 10, 2000. Witnesses testified about the “love bug” computer virus that infected over 10 million computers worldwide, shutting down Internet servers and corrupting files. Testimony centered around how the virus spread so quickly, the impacts and damages, and what steps could be taken to prevent similar attacks in the future. The witnesses were third party experts, and not from Microsoft. The testimony, I believe, stands in contrast to the hearings in the present day on social networks in how relatively calm and rational, even in the midst of a crisis, the dialog was. Still, it is worth noting that the hearings made numerous references to the ongoing investigations of Microsoft and the global market "power" the company maintained.

Like so many crisis situations in management, at first managers (like me) think they will show up and save the day with some brilliant idea that no one thought of. Failing that (as is almost always the case), the next approach is to take several options and combine them into what seems brilliant but is ultimately unworkable. That’s assuming you don’t show up and just wish the whole thing wasn’t happening. That too is never the case.

Rob Price (RobPr), Outlook’s PM leader, and WillK led the discussion. Their view was clear. First, we would disable sending a bunch of file types of attachments that people routinely sent or opened if they showed up in an inbox. Essentially, this meant not sending executable code or files that ran when opened. Second, we would guard Outlook such that any programmatic access to the address book or attempt to send email silently generated a warning and disabled access. Finally, although wonky, we would treat all email as untrusted, which basically meant no matter how code was snuck into email it did not run without a lot of warnings. We would effectively quarantine email messages and isolate the user’s important Outlook data from any code.

These actions or guards could be enforced and customized by administrators in large companies.

The team wanted to talk about exactly how much “stuff” would break in the process. KurtD and Martin Staley (MartinSt), Outlook’s test manager, said that no matter how much or how little we broke customers would complain we broke either too much or too little. Some things were super simple. For example, large companies compressed their files before emailing them as attachments to save storage and bandwidth. A common way to send them without requiring a separate program to decompress them was to have the compressed file sent as an executable file, which was automatically decompressed and saved on the local hard drive when opened as an attachment. This extension to Outlook was popular. And it would be totally broken, rendering attachments invisible to recipients.

The debate was not whether to make these changes as soon as possible, but whether we should even enable companies to turn them off or somehow reduce the scope of protection. As veterans of the past few rounds of viruses, there was reluctance to enable IT pros to reduce the protections on a PC. Their assessments weighed the risk of an important boss or stakeholder not getting work done with the support costs across an organization if a virus were to surface. We knew with any option that some percentage of customers would side with more pain in after-the-fact remediation than the pain of prevention. It was the wrong tradeoff, but the kind that is often made in IT organizations when they are put on the defensive because of weaknesses of the products they are supporting.

What the team really wanted was permission to cause the pain. They knew what needed to be done but knew there would be pushback. They wanted to know I would support them. For that, I did not hesitate given how much pain we had already caused and how much they clearly understood about the problem and solution. There was so much going on to suggest this significantly undermined the whole value proposition of Office that I wondered if we would have to introduce Outlook-free versions of Office (and reduced pricing—everything always came back to pricing).

In four weeks, on June 8, 2000, the team completed the patch and made it available for download—the now infamous Outlook Email Security Update. It went out for Office 97 and 2000, Outlook 98, and Outlook 2000 and for all sub-versions of those products all around the world.

Four weeks might seem like a long time, but cleansing PCs of the problem was time-consuming and occupied IT. The antivirus vendors and email security products did their part. We notified PSS and field sales. Marketing prepared a library of materials, as did Support, who wrote detailed technical articles for the Microsoft Knowledge Base. We issued a long “interview” with me, as a news release, detailing all the fixes. We did calls with the major press outlets.

The rollout was bumpy. With every virus, the knowledgeable PC enthusiasts tend to take a blame the users stance when faced with an update that diminishes PC capabilities. We saw this with both Concept and Melissa. In the case of LOVE, features like mailing around code were precisely what enthusiasts did frequently, so they were rather irate. In forums they complained, “Who opens attachments from people you don’t know?” People are busy and expect PCs to work. They don’t view using a PC in the same vein as walking down a dark alley in a strange city. Quickly, the community took to trying to find workarounds for the security changes, but to no avail. Several declared that end-users should change a few IT settings we did provide to return to “normal.”

Enterprise admins behaved as expected. Some optimized for the near term. Others took the pain in changing workflow and incompatibilities. Outlook, with the email security update, was the new normal and eventually accepted. While in hindsight it all seemed easy, the idea of breaking an important ecosystem, for a new product especially, was antithetical to Microsoft’s focus on compatibility. What the team proposed and then delivered was gutsy.

Office continued to have fewer and mostly less severe viruses for decades to come. At least a part of that was due to the Outlook Email Security Update.

Tech enthusiasts, IT Pros, and even our beloved MVPs complained for years and wrote many articles pejoratively referring to the Email Security Update as they adjusted to a new normal for Outlook.

The world moved on. And it was a bit safer using Office and Outlook.

I worked on Outlook when the dreaded ILOVEYOU virus hit. I remember a lot of what you wrote here, but the thing I remember most was the team wide mail from Kurt or Will that essentially said “Memorial Day weekend is cancelled”. They said unless you had the equivalent of a note from your doctor, you were expected to come in and work over the entire Memorial Day weekend to help get the set of patches and updates built and tested. But we all knew how serious the issue was, so while there was some grumbling, a lot of the folks on the team, many who were younger, buckled down and worked over the long weekend to help finish the ILOVEYOU patch.

To make up for it, Kurt DelBene had the entire team plus spouses/SOs for a giant party at his amazing house on Lake Washington. My wife still talks about that party and house.

I vividly remember having to work around the Email Security Update for an in-house developed LOB application. There was a custom form I loaded into an Exchange Public Folder that Outlook would read when it was started. It contained controls to enable whatever was needed to get some of the old functionality back. If I recall correctly, it was pretty granular and I only had to turn on one or two of the options.