105. New Ultrabooks, Old Office, and the Big Consumer Preview

But one thing is knowable now: With Windows 8, Microsoft has sweated the details, embraced beauty and simplicity, and created something new and delightful. Get psyched. –David Pogue, NYT, Feb 2012

The previous section detailed the release of the Windows 8 platform, WinRT, for building Metro-style apps. In the reimagining of Windows from the chipset to the experience, we’ve covered all the major efforts. In this section, we will describe the latest in PCs that will contribute to Windows 8, which Intel called Ultrabook™ PCs We will also introduce the Windows Store where developers could distribute apps. The really big news will be the Consumer Preview or beta test for Windows 8 where millions will experience the product for the first time. It might surprise readers, just as with the Developer Preview, that the reaction to the product across many audiences was quite positive. Just how positive? And what in the world could the professional press and reviewers actually liked? And what did Apple’s Tim Cook have to say about all this?

Back to 104. //build It and They Will Come (Hopefully)

Following the //build conference we were feeling quite good. Not to belabor the point, but I recognize how challenging it is to take such feelings at face value given where the product ended up. In writing this and helping people experience the steps we went through at the time in sequence, my hope is that what comes to light is that we were not bonkers and in fact much of the industry was excited by Windows 8 as it emerged. Of course, there were skeptics and doubters, even haters, but as veterans of dozens of major products we’d seen this before and the volume for Windows 8 was not disproportionate. If anything, the excitement and optimism were higher. So where did things take a decidedly different direction? It was when after product emerged from the Developer Preview and a series of events including the widely distributed Consumer Preview, or beta, when millions of people would experience the product. The leadup to the Consumer Preview in March 2012 included some important steps in the process as well.

New Ultrabooks

On the heels of the //build conference in September 2011 Intel began kicking off an effort to reenergize the PC industry with a response to Apple, finally. Intel developed a series of specifications, financial incentives in the form of marketing and pricing actions, as well as supply chain activation to deliver on a new class of laptop. Intel called these Ultrabooks. We called them a blessing.

Intel was best positioned to drive this type of advance. It was always difficult for Microsoft simply providing the operating system to dramatically alter the hardware platform, even though many thought by virtue of building Windows we held significant sway. We certainly had influence, but ultimately Windows was a wide-open platform which meant hardware to support any scenario was under PC maker control. The few times we had tried to tightly control hardware specifications, such as with Tablet PC and Media Center PC, did not go well at all. Worse, such controls angered not just PC makers but our fans as well who always wanted to build PCs on their own and experiment with hardware components.

Unlike Microsoft, Intel had a unique ability to influence hardware specifications and their influence increased over time compared to Microsoft’s which waned over the years. Intel rallied the industry around Netbooks. While that was a failure, it provided a playbook that Intel could later follow. Before the Netbook, Intel almost single-handedly drove a consistent level of support for Wi-Fi with the Centrino line of chips, which bought both lower-power consumption and Wi-Fi to the standard business laptop. In these cases, and many others such as USB, SATA storage, integrated graphics, and more, Intel took on a broader role in determining components and building software drivers for Windows (and Linux) while making it easier for OEMs to adopt a complete platform.

The efforts were not pure altruism. Intel would use these complete component platforms to steer OEMs to specific price points for chips as well as unit volume commitments. With those in hand, Intel could broadly advertise the platform using their massive Intel Inside advertising budget. These financial incentives were eagerly embraced by OEMs and a key part of their margin. Intel maximized its own margins as well by careful choice of CPUs in these platforms and enabling OEMs to upsell to even higher margin chips as appropriate.

This dynamic is why competing with the new Apple MacBook Air starting in 2008 followed by subsequent models and then Intel-based MacBook Pros proved elusive. Conspiracy theorists would believe that Intel was slow-rolling competitive PCs just to keep Apple and Steve Jobs happy. I never saw any indication of such a dynamic. Rather, it just seemed like PC makers were basically fat and happy in their share battle with each other. They had little worry about the 3-5% of share Apple had especially because they viewed Apple laptops and their customers as high-end, expensive, and premium. The PC business was all about good price and great volume. Being a pound heavier, an inch thicker, and plastic made little difference. As Apple share among influential customers, especially in the US, increased, the urgency from Intel and PC makers changed.

![Intel shows progress on ultrabook vision Rick Merritt 9/14/2011 3:57 PM EDT SAN FRANCISCO - Intel showed stepwise progress rallying the industry around its concept of the ultrabook, a thin and light system it believes represents the future for notebooks and tablets. The advances come in the wake of a mania for tablets driven by Apple's ARM-based iPad and the first details about Windows 8 for ARM processors. At the Intel Developer Forum here four Taiwan ODs showed prototype ultrabooks using Intel's 22nm Ivy Bridge chips. The CPUs, first described yesterday, are now available in engineering samples with production Comment slated for early next year, said Mooly Eden, general manager of Intel's client PC group. Four system makers 9/16/2011 8:08 PM EDT Absolutely Bill. So called Tech Journalist, like here Rick, think ARM is a ... More... already ship ultrabooks help.fulguy based on the current Sandy Bridge CPUs-Acer, Asustek, Samsung and Toshiba. 9/15/2011 7:36 PM EDT Great comment. As much as I do love my iPad, I use it for very different things More... Eden also showed the first working version of Haswell, a 22nm follow on Frank Eory More Comments > to Ivy Bridge that aims to slash power consumption while maintaining performance. Haswell aims to deliver a 20-fold power reduction to enable a mobile system to live ten days in standby mode on a single charge. "Haswell will complete the ultrabook revolution," said Eden, showing the prototype chip running in a traditional desktop system. Ultrabooks require prismatic batteries typically using lithium ion polymer, new chassis materials and flash or ultra thin drives. About a month ago, Intel hosted conferences in China and Taiwan attended by more than 1,300 people to rally supply chain partners around the details of the vision. To achieve the ultrabook power targets, Intel is driving new power management initiatives among other component makers. For example, Intel has developed an LCD panel specification that saves system power by storing enough data to serve up a screen image without waking up the host CPU. The spec involves transitioning the panel interface from LVDS to embedded Displayport and putting less than a megabyte of memory in the panel electronics. The scheme could add up to an hour to the average life of a mobile system's battery, Intel estimates. Separately, Intel described yesterday a broad, emerging PC power management scheme called Converged Platform Power Management that will first be enabled under Windows 8. The approach involves aggressively scheduling power use across the system based on power parameters that components report to the system. Just how broadly component makers are buying into Intel's power management initiatives is unclear. In other initiatives, Eden reported two Taiwan system makers-Asustek and Acer -have committed to shipping systems next year that use Thunderbolt, Intel's latest high-speed I/O technology. To date only Apple and a handful of peripheral makers have shipped systems based on the link announced early this year. "You will see in more and more systems [using Thunderbolt] as we move forward," Eden said. Eden also invited a Microsoft executive on stage during his keynote to show Windows 8 running both on current Sandy Bridge ultrabooks and on an Atom-based reference design for a tablet. This week Microsoft is detailing Windows 8 at a separate conference in Anaheim, including its support for ARM-based processors from Nvidia, Qualcomm and Texas Instruments. Intel shows progress on ultrabook vision Rick Merritt 9/14/2011 3:57 PM EDT SAN FRANCISCO - Intel showed stepwise progress rallying the industry around its concept of the ultrabook, a thin and light system it believes represents the future for notebooks and tablets. The advances come in the wake of a mania for tablets driven by Apple's ARM-based iPad and the first details about Windows 8 for ARM processors. At the Intel Developer Forum here four Taiwan ODs showed prototype ultrabooks using Intel's 22nm Ivy Bridge chips. The CPUs, first described yesterday, are now available in engineering samples with production Comment slated for early next year, said Mooly Eden, general manager of Intel's client PC group. Four system makers 9/16/2011 8:08 PM EDT Absolutely Bill. So called Tech Journalist, like here Rick, think ARM is a ... More... already ship ultrabooks help.fulguy based on the current Sandy Bridge CPUs-Acer, Asustek, Samsung and Toshiba. 9/15/2011 7:36 PM EDT Great comment. As much as I do love my iPad, I use it for very different things More... Eden also showed the first working version of Haswell, a 22nm follow on Frank Eory More Comments > to Ivy Bridge that aims to slash power consumption while maintaining performance. Haswell aims to deliver a 20-fold power reduction to enable a mobile system to live ten days in standby mode on a single charge. "Haswell will complete the ultrabook revolution," said Eden, showing the prototype chip running in a traditional desktop system. Ultrabooks require prismatic batteries typically using lithium ion polymer, new chassis materials and flash or ultra thin drives. About a month ago, Intel hosted conferences in China and Taiwan attended by more than 1,300 people to rally supply chain partners around the details of the vision. To achieve the ultrabook power targets, Intel is driving new power management initiatives among other component makers. For example, Intel has developed an LCD panel specification that saves system power by storing enough data to serve up a screen image without waking up the host CPU. The spec involves transitioning the panel interface from LVDS to embedded Displayport and putting less than a megabyte of memory in the panel electronics. The scheme could add up to an hour to the average life of a mobile system's battery, Intel estimates. Separately, Intel described yesterday a broad, emerging PC power management scheme called Converged Platform Power Management that will first be enabled under Windows 8. The approach involves aggressively scheduling power use across the system based on power parameters that components report to the system. Just how broadly component makers are buying into Intel's power management initiatives is unclear. In other initiatives, Eden reported two Taiwan system makers-Asustek and Acer -have committed to shipping systems next year that use Thunderbolt, Intel's latest high-speed I/O technology. To date only Apple and a handful of peripheral makers have shipped systems based on the link announced early this year. "You will see in more and more systems [using Thunderbolt] as we move forward," Eden said. Eden also invited a Microsoft executive on stage during his keynote to show Windows 8 running both on current Sandy Bridge ultrabooks and on an Atom-based reference design for a tablet. This week Microsoft is detailing Windows 8 at a separate conference in Anaheim, including its support for ARM-based processors from Nvidia, Qualcomm and Texas Instruments.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!As-8!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7bb458ee-7175-4494-8830-7bef2e157136_2261x1693.jpeg)

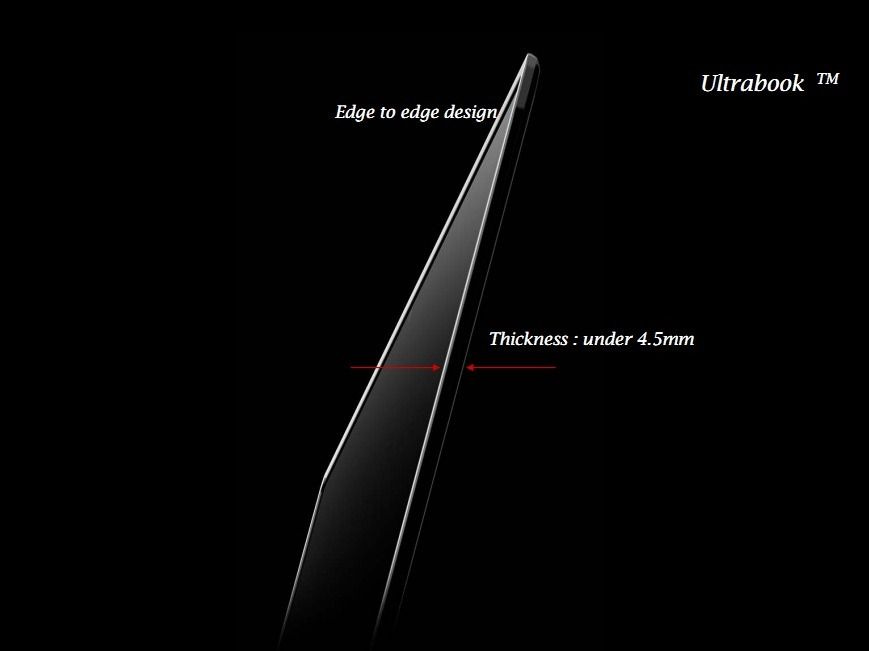

At the 2011 Intel Developer Forum (IDF) in Taiwan and in parallel with the //build Conference, Intel unveiled a new concept PC, the Ultrabook™. An Ultrabook wasn’t an actual PC from Intel, but a series of specifications or requirements for a PC to inherit the Ultrabook label, and thus the CPU pricing and broad co-advertising that came with it.

Unlike Netbooks and Centrino, Ultrabook specifications were rather detailed and covered a broad set of criteria beyond even the components Intel provided. The tagline Intel chose was “Thin, Responsive, and Secure” which would be used quite broadly. Among the requirements to be part of this program, new PCs had to include:

Battery. A good deal of the platform effort was a new type of battery that was not yet used broadly on Windows PCs. Ultrabook PCs required non-removable Li-Poly batteries of 36-41WHr designed to fit around components and a minimum of 5 hours of runtime.

Storage and Responsiveness. While not required precisely, there was a strong recommendation to use solid state disk drives, SSDs, in Ultrabook PCs which would significantly improve performance. SSDs also made it possible to strongly recommend a wake from standby time of just 7 seconds, which for Windows PCs would be excellent at the time.

Chassis Design. For the first time, Intel specified what amounted to innovative chassis design. For laptops with 14” or larger screens, the chassis needed to be under 21mm and for smaller screens 18mm.

Screen. The Ultrabook specification included guidelines and requirements covering display selection as well, including detailed values for thickness, bezel size, viewing angles, pixel density, and power requirements. At IDF, Intel showed off displays from a number of display makers who were ready and able to supply screens.

Keyboards. Even keyboards, far from Intel’s expertise, received attention. Back-lights, spill resistant layers, key-travel and key shape were all specified in Ultrabook design. This was a significant departure for Intel and the requirements created the need for keyboard redesign for all laptops.

Sensors and devices. Intel even included recommendations for devices usually seen far off the motherboard including: 720p webcam, accelerometer, GPS, ambient light sensor and more.

Intel really geared up the supply chain. This was crucially important during the huge ramp up happening with mobile phones where many suppliers were thinking of moving on from PCs. As it would turn out, Ultrabooks were the last gasp for innovative PCs.

Ultrabook laptops would turn out to be the ultimate devices for the road warrior running Office. These even led to the standardization of HDMI connectors in conference rooms after decades of VGA/RGB connectors. Windows 7 had introduced the command Window+P to make it easy to switch thus ending the need for degaussing and rebooting PCs to project…mostly. The stellar work at the device and OS kernel level to reduce power consumption, improve boot time, and even the unique features for SSD storage all contributed greatly to a fantastic experience for this new form factor.

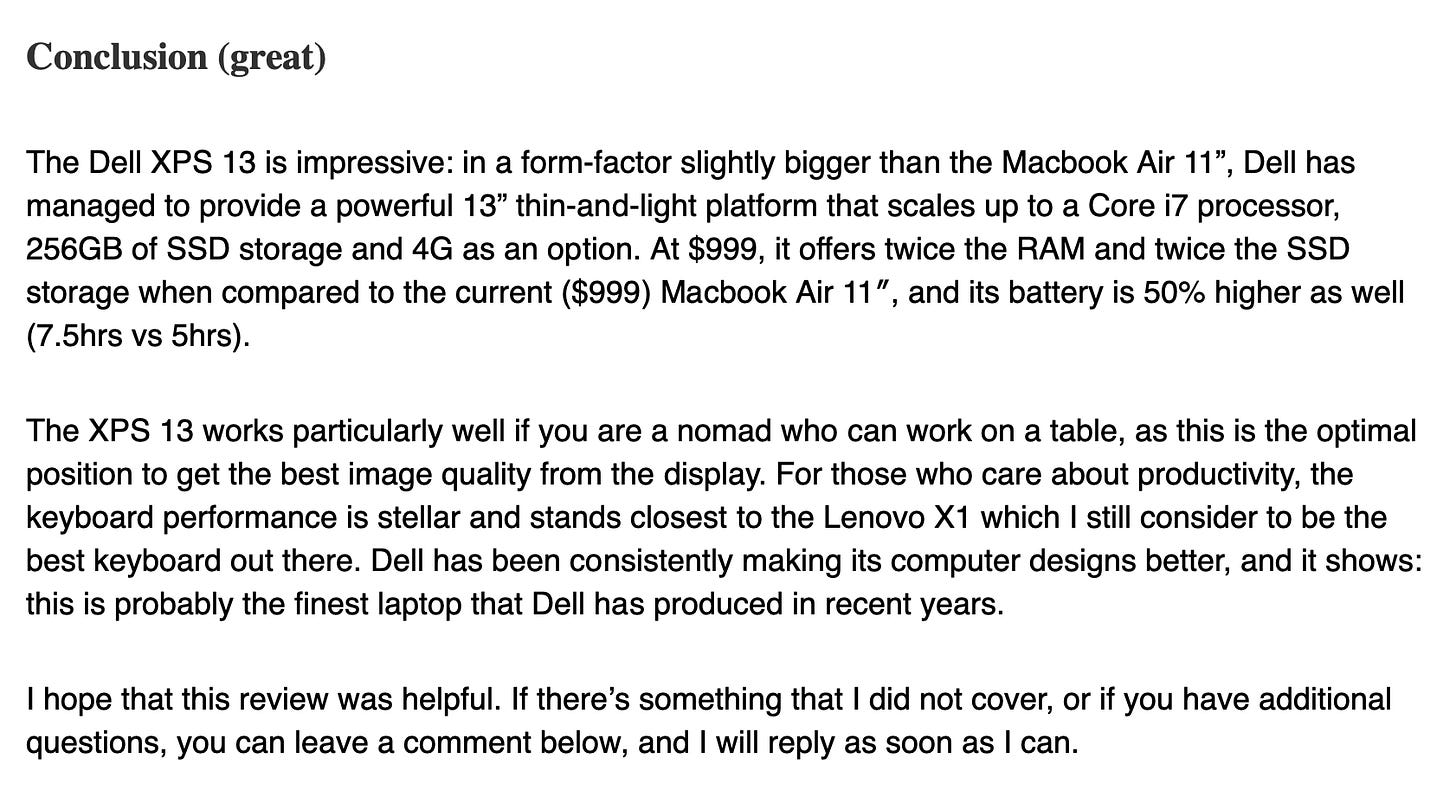

Ultrabooks brought Windows hardware to the 21st century and were far more competitive with Apple laptops than we might have expected after waiting so long. In fact, Ultrabook PCs were downright cheap compared to Apple products. While most would retail for the magic number of $1,495 many could be had for the other magic number of $999. This compared to nearly twice as much for the similarly configured Apple laptops. All in all, this was a huge win for the Windows PC. Every PC laptop today owes its existence to this excellent work by Intel and the supply chain. A small benefit for tech enthusiasts and IT administrators was that the wave of Ultrabook standardization also made it possible to install Windows without requiring additional drivers to be downloaded from PC maker sites.

Ultrabook PCs rapidly diffused across the ecosystem from the board room to executive teams to consultants and eventually to students. I remember a 2011 recruiting visit to MIT and Harvard and while I saw a lot (perhaps majority) of MacBooks, the PCs I saw were all newly purchased Ultrabook PCs with their sleek, un-PC-like aluminum cases.

Many believed Ultrabooks would put a dent in iPad momentum. Once again, it is worth a reminder that Apple’s iPad was absolutely top of mind for the industry. The iPad was the holiday gift for 2011. Apple sold over 32 million iPads in 2011 and the tablet redefined the baseline requirements for a road warrior productivity computing. Apple, hoping to sell every Apple customer on an iPhone, MacBook, and a new iPad remained relentless in the distinct use case for iPad while also continuing to tout the iPad as the future of computing.

It was this spike in demand for iPads that drove the difficult conversations with the Microsoft Office team about the role of Office on Windows 8, specifically Windows 8 on ARM processors, including the ARM device we were developing in-house that was quite secret at the time.

Old Office

We always knew going into Windows 8 planning that developing a new platform and new API meant also enlisting the support of the Office team. This was not some innovative thinking on our part, but literally the Microsoft playbook from the founding of the company.

A platform cold start requires a huge leap of faith from the consumers of the platform. The best way to seed interest in the platform is to have flagship applications that can be demonstrated to other developers to get the flywheel going. Cool apps on a platform attract more app developers which lead to cooler apps. Sometimes this is even labeled “killer application” though I think that is a bit dramatic since it doesn’t kill but brings life to the platform. Having Lotus 1-2-3 on MS-DOS, Microsoft Excel, Aldus PageMaker, and also Microsoft Word on Macintosh cemented that platform. Excel and Word were crucial to validating Windows and even to Microsoft’s ability to complete building Windows for significant applications. Ultimately Office on Windows 3.0 proved to be a tipping point for Windows. In a turn of fate, Windows also proved to be critical to the success of Office as a productivity suite. Microsoft not only came to define this virtuous platform cycle but benefitted itself with Office.

Platform shifts offer a unique moment when all bets are off, and the new leaders can emerge. It is why Bill Gates was so tuned in to creating and betting on platform shifts and why Silicon Valley always seems to be seeking out these moments. Recall from the earlier section 011. Strategy for the 90s: Windows, that platform shifts can be so dramatic that even within a company people decide to quit over them. My first manager and programming legend Doug Klunder (DougK) famously left Microsoft in the early 1980s over the strategy change to build a Macintosh spreadsheet rather than ship the MS-DOS spreadsheet that he had built and was certain would beat Lotus 1-2-3. That spreadsheet and Doug’s recalc invention (minimal recalc) formed a core part of Microsoft going forward and Doug later returned.

As discussed previously, many describe nefarious means to the rise of Office on Windows compared to Lotus 1-2-3 and WordPerfect among other leading MS-DOS productivity tools. Within the leaders of MS-DOS applications, none prioritized Windows above all other platforms. Instead choosing to nurture their existing MS-DOS successes and character-mode user experiences. Microsoft uniquely bet on Macintosh and then Windows, perhaps because it lacked the mega-successful MS-DOS applications business the others possessed. Nevertheless, Microsoft bet and bet big and bet early. The rest is history.

Little did I and the other leaders on Windows 8, all of whom had previously worked on and led Office, realize how the tables would turn. Here we were at the start of Windows 8 knowing that we would be introducing a new platform and fully aware of Microsoft’s own playbook. We knew it would take convincing but at least for me I failed to fully internalize just how difficult it would be for Microsoft to collectively make a bet on a new platform.

At the Windows 8 Vision Meeting, I sat next to Steve Ballmer and the guests from across the company, including the leaders of Office. We showed Office running in the prototype sketches just as we showed Office running in January 2011 on ARM at the CES show and then later at //build. The Office everyone knew and loved running in the desktop. It was right then at the Vision meeting that SteveB leaned over to ask me about Office for tablets and the new platform.

I said, definitively, that we had a huge chance to build a new kind of Office application for this new world of mobility, tablets, touch, and more. It wouldn’t be like the current Office, and it wouldn’t be like browser Office—the project started back when I was in Office. We had a chance to define the new user interface paradigm for this new style of productivity, much as how Office came to define the user interface paradigm for mouse and keyboard.

We had many conversations with the Office team throughout building Windows 8. Our goal was simple—convince the team to build a new kind of app for the new Windows 8 platform. We did not want to port the existing apps to Windows 8 any more than we wanted any ISV to do that. Microsoft’s own experience with the first version of Word for Windows, a legendary mishap caused by trying to port code from one platform to another, was enough of a lesson to create institutional knowledge of the risks of doing that. Even the early releases of PowerPoint on Windows suffered from the difficulties of trying to port from Macintosh. Many might remember the difficulties Microsoft had with Word 6.0 for Macintosh which did not fully embrace the look and feel of Mac and disappointed.

The world changed a great deal with iPad and web browsers. The historical strengths of Office focused on fine grained document control for printing gave way to multi-player (a recent nomenclature for multi-user) collaboration, sharing, and online consumption, and considerably less demand for formatting. There would be ample opportunity for a new type of application. Perhaps if we collectively developed that, we thought, we could avoid the pressure to provide Office per se for Windows 8, which we knew would be a massive undertaking for a new platform, even futile.

Office was eager to experiment with OneNote, which was supporting mobile, browser, and more and was widely praised for an innovative experience in an important scenario. Doing something more significant was proving a challenge and a bit frustrating for us. In order to understand the situation, it is important to recognize the situation Office found itself in in 2010 and what really drove strategic choices.

Historically, the biggest factor in weighing choices for Office has been the maintenance of the value of the overall bundle (Word, Excel, PowerPoint, Outlook, and the Access database) and with that the pricing. Key to maintaining that value was compatibility with “full Office” meaning the complete feature-set of desktop Office. In other words, when sales and marketing were confronted with either a lower-priced or less-featured variant of Office the response was to focus on backward compatibility for dealing with old files and email attachments from anywhere, on the familiarity with the user interface, aka the Ribbon, and on the value of the bundle. By 2010, the Office brand came to represent the Ribbon user interface, the full Office feature set, and support for documents and custom Visual Basic solutions that existed across thousands of enterprise customers.

Office continued to face somewhat acute challenges to the business from Google Apps (previously Google Apps for Your Domain, often colloquially called Google Docs, more recently G Suite, today known as Google Workspace.) Google pushed Google Apps relentlessly through the incredibly successful Gmail launch, something we would do with Windows Live and the Office browser-based applications. Google Apps was making real progress in the academic market, where the product was usually free. Small business was also adopting Google Apps owing to the push via Gmail and the easy use of the apps after registering an email domain with Google. Most importantly, enterprise customers under budget pressures following the Global Financial Crisis also began to consider Google Apps. Use of a difficult economy to put price pressure on Microsoft was something I’d experienced through every downturn since the Gulf War. Customers not only had the option of Google Apps, but they could also maintain full compatibility with Office by simply sticking with the Office they already owned and not upgrading, putting the Enterprise Agreement renewal in jeopardy. Losing even a single deal had the appearance of a “share shift” and a series of 3 deals would likely be followed by industry analyst quotes or even press releases from Google, and suddenly there was a trend.

The presence of this competitive threat made offering anything at all new seem risky. A new product would call into question the value of “full Office” and certainly anything priced at app store level pricing would draw attention to the nearly $200 per year Office was receiving in enterprise agreements, which today could be over $40 per month for Office 365. With a few thousand Enterprise Agreement customers, taking on this kind of product challenge was a level of risk that the Office team was not going to be comfortable with all that easily.

Office for Mac, long mostly out of sight and out of mind, had become a lot more interesting of late. Back when I was in Office and following the release of Mac Office 4.x and Windows Office 95, the legendary deal between Steve Jobs and Bill Gates was struck. Most recall this deal through the lens of antitrust and Microsoft throwing Apple a life preserver just as Steve Jobs returned to a company on the brink of bankruptcy. Microsoft indeed paid apple $150 million in exchange for patent rights which would ensure the end of litigation between the companies. In exchange, Apple also received a commitment to Macintosh and that Office would continue to support the platform. It was then we (in Office) created the Macintosh Business Unit (MacBU) staffed at 100 engineers to start. The goal for us was to stop kidding ourselves about doing a great job of cross-platform support and let the Mac team focus on Mac and the Windows team focus on Windows, with judicious code sharing as the MacBU, staffed with Office engineers, deemed necessary. From that time forward, August 1997, the Mac team went merrily on its way as did Windows.

Each of the subsequent leaders of MacBU were deeply connected to Apple, and discretely so. The business relationship required that. Most of Mac Office was sold not through Microsoft’s typical enterprise accounts but direct to individual customers. As Apple’s new retail stores scaled, the sales of Mac Office through that channel quickly became the primary means for Apple customers to acquire Office. MacBU found itself somewhat beholden to Apple for distribution, price support, and even launch PR. In exchange, MacBU dedicated its efforts to being a fantastic client of the Mac OS as it evolved. Such support had become increasingly difficult as Windows and Mac diverged and then as Mac became a diminishingly small part of the overall business, unlike the 1980s when it was more than half the business. The deal created a win-win for Apple and Microsoft, not to mention Apple customers.

Part of the relationship between MacBU and Apple included early access to Apple technologies under development, exactly as Microsoft had done for Windows with leading vendors. By offering this, Apple hoped to garner MacBU support for the latest platform technologies. The transitions Apple made to the new OS X and then later to Intel processors all but required Office to be present from the first days of availability. Apple knew this. MacBU knew this. Our industry knew this. It was the way platforms worked.

As part of this work, MacBU also began to migrate the Office code base from the older Macintosh operating system APIs to the new OS X APIs called Cocoa. As previously mentioned, Apple had a different way of evolving the OS compared to Microsoft. Apple not only strongly encouraged ISVs to move to new APIs, but it also obsoleted APIs thus requiring ISVs to move. Sometimes with their big code bases, the important ISVs would slow roll these moves. Adobe was (and remains) legendary for its slow pace of adoption. MacBU tended to be nimble, due at least in part to the ever-present connection in the Apple retail stores. Plus using the latest was a pretty cool thing to do in the Mac community.

As Apple’s new tablet came into existence, MacBU had to decide what to do to support it long before the general public or anyone else at Microsoft was aware of the project. To its credit, MacBU guarded Apple trade secrets just as Apple would have hoped. No one outside MacBU was aware of this project. Apple lobbied the team to make Office for iPad. Part of the promise was that the new iPad APIs were reasonably close to the OS X APIs and the work would not be crazy, taking advantage of the migration to Cocoa.

Of note, this was decidedly not an approach taken by Windows 8. Apple had already spent a generation modernizing the APIs for the iPhone and pushing ISVs to adopt more modern approaches for Mac. In other words, they were way ahead of Microsoft.

It was not quite so simple though. Apple threw a few wrinkles in the mix. First, Apple had put a good deal of effort into its own suite of Mac apps, called iWork, which were direct competitors to Office. This proved frustrating for Microsoft and also provided leverage for Apple. If MacBU didn’t follow an Apple strategy, Apple would for its own iWork.

Second, iWork was cheap. At the early days, iWork cost $79, substantially less than Office which usually sold for $150 but up to $280 with Mac Outlook. MacBU was no happier about a low-priced competitor than Windows Office was, but this was especially problematic because of the first-party nature of this competition. Whatever MacBU offered for the future tablet was going to need to be price competitive or face a real uphill battle.

Related to this, the iPhone app store already demonstrated that pricing for apps would be much lower and much less favorable (to ISVs) than selling boxes of software at retail. Few apps sold for more than $9.99 and all had a perpetual license for as many devices as someone owned. That was not close to the level of pricing (and margin) to support the MacBU R&D commitment, especially without significantly more volume.

Third, the iPhone OS and by extension this future tablet would not initially support “full Office” for all the same reasons that Windows 8 would not be able to. The security model, the user experience, and even the setup and distribution tools all were substantially less functional or at least different enough. Simply porting Office to the tablet was no more possible for MacBU than it was for Windows Office supporting Windows 8. Maintaining the complete meaning of the Office brand—and the name—along with the price point would be impossible.

The concerns over pricing, cannibalization, and the Office brand on the new Apple tablet mirrored those of the Windows Office team. Still, unlike the Windows team, the Mac team began investing in the new tablet and by the time we were deep in discussions about Office and Windows 8 there was substantial progress on Apple’s new tablet OS. I did not know this at the time, but once the iPad was announced I was made aware.

This created an awkward situation. If there was indeed a new, or a port, of Office for iPad but not an equivalent product for Windows 8, Microsoft would look confused at best or dumb at worst. MacBU was caught between its own business needs and the strategic needs of Apple while the Windows Office team was caught between its business needs and the strategic needs of Microsoft overall.

Meanwhile the Windows Office team was doing great work retargeting Intel-based Office to run on ARM processors. This was not trivial or zero work but was super well-understood. Much like Windows NT, Office had for a long time been insulated from the specifics of chipsets and instruction sets. So long as the compiler could generate the right code and the Win32 APIs were available the effort was straight-forward. Going as far back as the January 2011 CES meeting, Office had native builds of Word, Excel, and PowerPoint for ARM using Win32 and these were important to our demonstrations of SoC support.

Our plans, however, did not include making the Win32 API available to third parties on ARM. As described previously, the Win32 API for apps presented many challenges on ARM including power management, security including viruses and malware, and full integration with the Metro user experience such as contracts for sharing information. Outlook was particularly problematic when it came to its power usage due to all the background processing. After a decade of fine tuning, the power profile for Word, Excel, and PowerPoint were excellent, far better than most all Windows software.

We intended to provide the desktop for working with files in Windows Explorer along with the traditional control panel for settings. Admittedly, this would prove to be the source of more confusion than convenience. Still the situation was not unlike that of the MS-DOS command box on Windows to some degree, especially on the non-Intel versions of Windows NT.

The bigger problem would be how an ARM device would require a keyboard and mouse to use desktop versions of Win32 Office apps as well as the Windows desktop itself. While all ARM devices would support a keyboard and mouse, not all would have one readily available as some would be pure tablets like the iPad. The Office team introduced some user interface redesign to better support touch, but at a fundamental level Office required a mouse and keyboard for any sort of robust usage.

After a series of difficult conversations culminating in an executive staff discussion we arrived at an end-state where we would ship Win32 desktop versions of Word, Excel, and PowerPoint and Metro-style OneNote. It is not without irony that I reflected on the fact that OneNote exists because we (in Office, me and others) made a bet on the Tablet PC edition of Windows when the team building the OS failed to demonstrate user interface mechanisms or scenarios for how or when a pen could be used for word processing or spreadsheets. Not only did we feel we had ample user interface metaphors we also believed we articulated the type of platform changes around touch, cloud, and mobile that could be incorporated to build a new and unique productivity tool.

When it came down to it, the Office team did not want to invest in a subset of Office, reduce the brand value proposition for the apps because they would lack support for Visual Basic and other enterprise features, or take on the risk of developing something entirely new. The biggest challenge for Office on iPad would prove to be the same as many other existing ISVs faced, the iPad app pricing and licensing model. Office was early moving customers to Office 365 and on Mac the business was still the $150 perpetual license. There was no way to charge that much for apps on iPad at the time, especially with Apple apps priced at $9.95. The App Store rules would prove complicated for Microsoft as well, who would not want to cede subscription revenue to Apple. I’m sure there were many discussions with Apple that I was not part of.

Ultimately, the Microsoft Office team had the same choice to make for the iPad as it did for Windows 8 but chose one way for the iPad and the other way for Windows 8. It was the same type of platform choice faced 30 years earlier when the Microsoft Apps team faced building a spreadsheet for MS-DOS or for Macintosh and then Windows.

I obviously understood all these reasons deeply from my own first party experience. At the same time, the company’s choice felt to me like the most conservative approach we could take at a time when we needed to be taking on more risk. The company was going through a difficult period and was getting beaten up for the risks it was taking by investing across search, gaming, web, and because of the inability to get ahead on smartphones and browsing. Reducing risk to Office at a time like this is what can happen when a company sees defending the existing business as the top priority over what could viewed as innovation or new opportunity. Platform shifts are extremely difficult for the existing leaders, and Office was a leader on both Mac and Windows.

On ARM devices the lack of Metro-style Office (also called Office for WinRT) would prove even more confusing to the market because it would appear as though we were holding back key platform capabilities by not making it so simple to port applications to the desktop. We knew there would be little interest in providing native ARM applications from third parties who would have to go through all the effort to port and support when there were plenty of Intel-based systems out there for their customers to use. Most desktop applications for sale that were under active development were also the kind of tools that required high-end PCs and were not optimized even for laptops, applications such as those from Adobe, AutoDesk, Dassault, and the like.

Apple provided iWork for the iPad from the initial launch of the iPad in 2010. They used the iPad as an opportunity to purpose-build tablet apps. By 2017, iWork was free across all platforms. Apple had nothing to defend and only benefitted from the effort to support the platform, so I suspect this was all relatively easy for them to do.

During that executive staff meeting we had the difficult discussion about the existing iPad apps for Office as well. In this case, the same concerns expressed about Office for WinRT existed for Office for iPad. The only difference was that Office for iPad was well on its to being done by late 2011. The team was concerned about what to call the apps, the lack of Outlook for iPad as they had only built Word, Excel, and PowerPoint, and the feature differences between the apps on iPad and Windows. Outlook would follow many years later, based on an acquisition of a Silicon Valley startup. Office settled on a business model where the apps were free for existing 365 subscribers or a $99 in-app purchase. Non-subscribers could use the apps to view, but not edit, documents. It would be messy and frustrating for customers who were searching the Apple App Store for “Word” and “Excel” in huge volumes and finding nothing from Microsoft.

Collectively we agreed that it would be embarrassing for Microsoft to have tablet apps first on iPad and then never on a Windows PC. The subset of Office apps would be released for iPad in March 2014. In 2021, Microsoft released an all-in-one app called Office, which supported each of the apps in a single download as well as Microsoft’s cloud storage, OneDrive.

The world was waiting for validation from Office for the new Windows 8 platform and would only see that through OneNote, which was a nice addition but not the killer app that platforms require. While I am certain there is no one aspect to Windows 8 that contributed more than any other to the market reception, the lack of Office designed for Windows 8 was a top issue.

Big Windows 8 Consumer Preview

The march of external Windows 8 milestones continued.

After the //build conference that was so energizing we held an event highlighting the app store that would be part of Windows 8. We held the event in San Francisco and ran through the economics of the store and the opportunity for developers. Antoine Leblond (Antoine) led the entire event as he’d also led the team building the store from scratch.

The Windows Store was another part of the whole of Windows 8 that went from a blank slate to complete offering in the span of the release. By the end of 2011, just months after the //build conference we already had the store up and running and soon developers were able to exercise the app submission and approval process. As with the WinRT API we had the process and tooling well-documented. There were no major hiccups, and the store did what we needed it to do and did so gracefully.

From the time of the Store event through the broad beta test, the marketing and evangelism teams worked tirelessly to onboard developers of all sizes and get their apps into the store. Going from 17 sample apps from interns and the apps built by the Windows team (Mail, Photos, Calendar, Contacts, and more) to hundreds of apps available just after beta including many first-tier consumer apps was a huge accomplishment.

The final major event for all of Windows 8 was to release the broad beta test. Normally we would not have a special event for a beta but given the huge change and major effort involved in releasing a new platform we chose to use the massive mobile telephony industry meeting, Mobile World Congress (MWC), in Barcelona, Spain to announce and make available the Windows 8 Consumer Preview. This would be a downloadable release available to anyone right after our press event on February 29, 2012.

MWC was also the big event for Windows Phone and usually where there were big announcements. The 2012 show was between phone releases, with Windows Phone 7.5 already in market and Windows Phone 8 still under wraps for an end-of-year launch coincident with Windows 8 for PCs.

Therefore, the big news for Microsoft would be the broad beta test for Windows 8. We were excited. So far, while there were questions and certainly challenges, primarily bootstrapping the new platform, we’d seen positive results from developers, launched the Windows Store, and the product was solid. The Consumer Preview was a refinement of the Developer Preview, with no major strategic changes from the release less than six months earlier.

The event was only for press held in a jam-packed tent of about 200 people. We were feeling pretty good about the planned presentations. While there was no strategic news, we had made over 100,000 product changes since the developer preview.

Our primary message was the complete Windows 8 story: the operating system, apps, the Windows Store, and PCs and peripherals that would shine on Windows 8. While the world was fixated and obsessed about tablets, we continued to emphasize our message that computing devices were converging. Mobile platforms were rapidly gaining capabilities and in many ways such as power management and sensors surpassing Intel-based PCs. On the other hand, Intel-based PCs had a quality resurgence with Ultrabook specs and Windows 8 would bring touch capabilities and proper apps to Intel PCs with touch screens. I would always emphasize that we expected traditional laptops to incorporate touch screens and remind people that at some near future all their screens would have fingerprints.

Julie Larson-Green (JulieLar) and Antoine Leblond had a series of demonstrations including the Windows 8 experience and many apps that had been submitted by developers to the store. The progress in just a few months on the Windows Store and third-party apps was a positive sign for the platform overall.

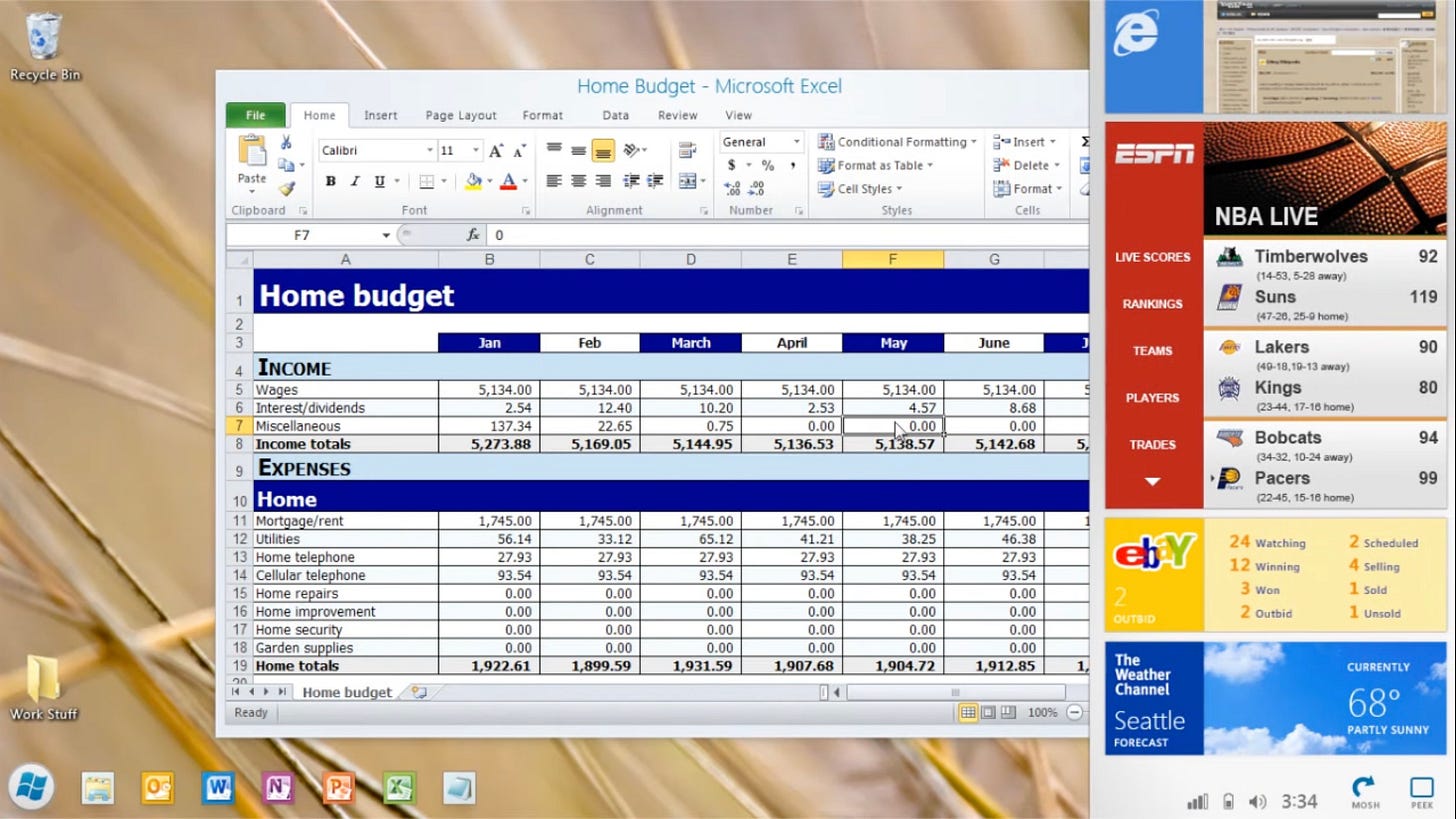

Mike Angiulo (MikeAng) and I showed off a very exciting and broad range of Windows 8 PCs from small tablets through a giant Perceptive Pixel 82” touch screen, the kind used on CNN for election night. The emphasis was on how Windows scales across the form factors and price points all with a single operating system.

Following the conclusion of the event a press release went out detailing the availability of the Consumer Preview for download. Within less than a day, the release was downloaded a million times. The Windows team back in Redmond was more ready than we were at the Windows 7 beta, standing by for the download traffic. Everything went smoothly.

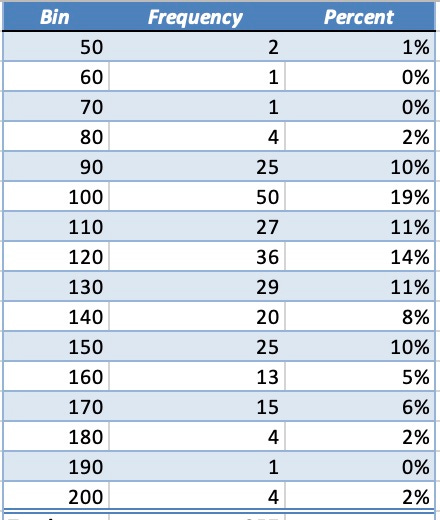

The press coverage of the event and importantly the reviews for the release were quite good. I know as you read this, you must be wondering if I had too much Cava in Barcelona. How could professional tech reviewers possible like Windows 8? They did. I swear. In the first couple of days, we had over 250 first looks and reviews. Nearly 70% of them scored over 110 on the PRIME score measuring overall tone, where 100 is neutral. There were 4 perfect scores at 200. Only 13% were scored 90 or less, and this is during an era where Microsoft typically averaged 90 on most product launches.

Like the Developer Preview, across mainstream media, tech enthusiast press, and even broadcast we received an incredible volume of positive to effusive comments. I sit here today writing this and I know readers must think there is either highly selective editing on my part or some sort of conspiracy to rewrite the past. I can assure you it is neither. In writing Hardcore Software, I made it a point of researching and rereading much of the contemporary press for every product, even Windows 8 product reviews.

We spent two weeks on the road with the press doing briefings and dozens of outlets received the Samsung tablet from //build and the near final Consumer Preview release. Unlike most previous Windows releases we did not run into technical problems, but rather I received quite a bit of private communication expressing positive impressions and almost a surprise at the combination of radical and yet comfortable the Windows 8 experience seemed to be. Once the release was available, reporters started to comment in their reviews, blogs, and even tweets:

“Brace yourself, Windows users. Microsoft’s operating system is poised for stunning, dramatic change.” —Christina Bonnington of Wired

“By the time the final version ships later this year, it’s clear that Windows 8 is going to be a remarkable, daring update to the venerable OS. It is a departure from nearly everything we've known Windows to be. You will love it, or hate it. I love it.” —Mat Honan of Gizmodo

“In short, Windows 8 is elegant, dynamic and beautifully created.” —Jeremy Kaplan of FoxNews.com

“It’s an interface that’s girding itself to compete with the iPad as much as the Mac, even though it’s not an iPad knockoff.” —Harry McCracken of TIME

“Windows 8 is evidence that the old tech company is quite capable of bold moves and impressive innovation.” —Michael Muchmore of PC Magazine

“One thing is knowable now: With Windows 8, Microsoft has sweated the details, embraced beauty and simplicity, and created something new and delightful. Get psyched.” —David Pogue of The New York Times

“Don’t confuse the friendly interface with superficiality. This is Windows and can do all the things we’ve come to expect on a Windows PC.” — Wilson Rothman of MSNBC.com

“The first beta of the next-gen operating system is eminently touchable, definitely social, and maybe just a bit sexy.” — Seth Rosenblatt of CNET

“Overall, I’m extremely impressed with the next version of Windows – the features, the new ways of interacting with a tablet, and the potential of it all.” —Joanna Stern of ABCNews.com

Even the first apps available in the Windows Store were receiving positive feedback. The quality of the apps available in the store was quite good. This was very early in the mobile apps era. This makes it difficult for most to think back to how relatively basic the software was at the time. Android apps were notoriously flakey and while there were huge numbers of iOS apps, most did not do very much. In evaluating the first apps from the Windows Store, Joanna Stern of ABC News (a new beat after moving from The Verge) tweeted “First impression: the apps I see for Win 8 are already 100x better than the ones for Honeycomb or ICS [Ice Cream Sandwich, the code name for the next Android release]. Very exciting.”

Techmeme and Google News (which was the new cool place to look for headlines) were filled with coverage and positive headlines. Google News registered over 9,200 stories from the sources it crawls. This was our first Twitter-centric release and Windows 8 had almost 200,000 tweets in the first 24 hours, at peak there 20,000 per hour. It might not seem like a lot, but the Twitter-verse was relatively small in 2012, at just over 100M.

One of our perfect score reviews, a 200 PRIME and 5 on message pickup, came from David Pogue at the New York Times. Pogue was no fan of Windows and was super well-known as an author and expert on Apple products. He wrote books on all the major systems and devices but was always a bit grouchy when it came to Windows. I had flown down to San Francisco to meet with him and pre-brief on Windows 8. He gave me an earful and I was quite concerned about the pending review. I wanted to share a bit of what the review had to say:1

It’s a huge radical rethinking of Windows — and one that’s beautiful, logical and simple. In essence, it brings the attractive, useful concept of Start-screen tiles, currently available on Windows Phone 7 phones, to laptops, desktop PC’s and tablets.

I’ve been using Windows 8 for about a week on a prototype Samsung tablet. And I have got to tell you, I’m excited.

For two reasons. First, because Windows 8 works fluidly and briskly on touch screens; it’s a natural fit. And second, it attains that success through a design that’s all Microsoft’s own. This business of the tiles is not at all what Apple designed for iOS, or that Google copied in Android.

. . .

Swipe from the right edge to open the Start menu (with Search, Share, Devices and Settings buttons). Swipe from the left to switch apps. Swipe in and back out again to open the app switcher. Swipe down to open the browser address bar.

If you have a mouse, you can click screen corners, or hit keystrokes, to perform these same functions.

These swipes take about one minute to learn. On a tablet, I can’t begin to tell you how much fun it is. It’s evident that Microsoft has sweated over every decision — where things are, how prominent they are, how easy they are to access. (If you have the time, watch the videos to see all of this in action.)

. . .

But one thing is knowable now: With Windows 8, Microsoft has sweated the details, embraced beauty and simplicity, and created something new and delightful. Get psyched.

I want to be sure to capture both the grief he gave me in person and what he wrote in the review. Many reviews indicated that there could be potential for some to have difficulty using the product or even wanting to make a change, though the reviewers themselves did not express the difficulty. When it came to expressing the weaknesses of the Consumer Preview, Pogue said:

The only huge design failure is that Microsoft couldn’t just abandon “real” Windows completely — desktop, folders, taskbar and all those thousands of programs. So on a PC, hiding behind this new Start screen is what looks almost exactly like the old Windows 7, with all of its complexity.

In other words, Windows 8 seems to favor tablets and phones. On a nontouch computer like a laptop or desktop PC, the beauty and grace of Metro feels like a facade that’s covering up the old Windows. It’s two operating systems to learn instead of one.

. . .

Look, it’s obvious that PC’s aren’t the center of our universe anymore. Apple maintains that you still need two operating systems — related, but different — for touch devices and computers. Microsoft is asserting that, no, you can have one single operating system on every machine, always familiar.

The company has a point: already, the lines between computers, tablets and phones are blurring. They’re all picking up features from each other — laptops with flash memory instead of hard drives, tablets with mice and keyboards. With Windows 8, Microsoft plans to be ready for this Grand Unification Theory.

It’s impossible to know how successful that theory will turn out to be. Windows 8 is a home run on tablets, but of course it has lost years to the iPad. (The Zune music player software was also beautiful — it was, in fact, the forerunner to Windows 8 — but it never did manage to close the iPod’s four-year head start.)

This is as perfect as a review can get. As a note, the scoring of reviews is done by a separate research and data team at the PR agency and it as scientific as one could be at the time. Like an Olympic sport they do not like to give out perfect scores as it makes their job more difficult down the road.

Even Wall Street got in on the positive sentiment. Normally I would not have paid any attention at all to a financial analyst view on product design, but the analyst community had become part of the cycle around an ever-expanding Apple and an ever-shrinking Microsoft. Citi research department reported the following on March 11, 2012, in a report I received:

We continue to view windows 8 as a positive catalyst - Inputs since the Feb 29th Community Preview (beta) have continued to be positive with developer and IS momentum appearing to pick up. We continue to expect general availability of win 8 devices around Sept / Oct with ARM devices likely later (although MST and OEM goal remains coincident). Given long-term secular concerns, share gains in tablets or renewed momentum in the PC market in 2H should be positive catalysts for shares. We acknowledge that the stock has a tendency to "fade" post release and thus we believe stock performance beyond that depends on tangible success of release.2

What about the negative stories? There were some, just not that many. In fact, most of the truly negative stories were about specific features in the release. For example, one reviewer noted that ARM Windows 8 would not include Outlook, another bemoaned the lack of support for old-style enterprise management tools instead opting for modern mobile device management, and another was concerned about a keyboard change to the diagnostic boot sequence.

When there were negative stories, they did indeed carry the themes alluded to in the Pogue review. For example, Dan Acerman at CNET wrote in a review titled “Does Windows 8 diss the PC?”:

According to NPD Group, PCs are still the largest category for U.S. consumer technology hardware, selling $28 billion worth of desktops and laptops in 2011 (a 3-percent drop from 2010). Tablets and e-readers nearly doubled from the previous year, to $15 billion, but that was mostly on the continued strength of Apple's iPad. If you take iPad (and Android) out of the equation, interest in Windows tablets is still tiny. It will no doubt grow under Windows 8, but mostly because it has nowhere to go but up.

So just remember, while watching everyone pinching, swiping, and tapping their Metro interface tablets and convertible laptops over the next several months in product demos, the real work is, and will continue to be, done on traditional laptops (and, yes, desktops) for a long time to come.3

From our perspective this notion of “two in one” was quite similar to the review of Windows originally in how it was first used as a way to simply run MS-DOS applications in character mode. The two decades of seamless Windows compatibility across 16-bit, 32-bit, and 64-bit perhaps created an expectation that compatibility was always essentially transparent.

Over the course of the Consumer Preview millions of people would download and test the product. Many would write blogs, tweets, and record YouTube videos about their experience. Almost immediately, developers began to hack away at Windows and introduce utilities to bring back their favorite look and feel from past releases. All of this was perfectly normal. We’d seen this before in every release of Windows.

One competitor took time during their own earnings call to comment on Windows 8, which frankly was quite surprising. What he had to say would definitely become a meme for the record books. In the call, a financial analyst asked the following question of Apple’s Tim Cook:

I was wondering if you can talk about how you think about the markets for tablet and PC devices going forward. I think you've been fairly clear about saying that you believe that tablets will eclipse PCs in volume at some point. And I think you've also said they're somewhat discrete markets. There seems to be a lot of work, particularly on PC-based platforms, towards trying to combine the PC and tablet experience going forward in part because Windows 8 will be able to -- is a touch-based operating system as well. Can you comment about why you don't believe the PC or the Ultrabook and tablet markets or your MacBook Air and tablet markets won't converge? Isn't it realistic to think in a couple of years we're going to have a device that's under 2 pounds with great battery life that we can all carry around and open as a notebook or close up in a clever way and use as a tablet? Can you comment on why you don't think that product might not come or why you believe these markets are separate? (Tony Sacconaghi - Sanford C. Bernstein & Co., LLC., Research Division)

Tim replied as follows:

I think, Tony, anything can be forced to converge. But the problem is that products are about trade-offs, and you begin to make trade-offs to the point where what you have left at the end of the day doesn't please anyone. You can converge a toaster to a refrigerator, but those things are probably not going to be pleasing to the user. And so our view is that the tablet market is huge. And we've said that since day one. We didn't wait until we had a lot of results. We were using them here, and it was already clear to us that there was so much you could do and that the reasons that people would use those would be so broad. . . . I also believe that there is a very good market for the MacBook Air, and we continue to innovate in that product. And -- but I do think that it appeals to [somewhat --] someone that has a little bit different requirements. And you wouldn't want to put these things together because you wind up compromising in both and not pleasing either user. Some people will prefer to own both, and that's great, too. But I think to make the compromises of convergence, so -- we're not going to that party. Others might. Others might from a defensive point of view, particularly. But we're going to play in both.4

This was aimed squarely at our positioning of devices converging. It would be several more years before Apple would add a keyboard and a trackpad to the iPad Pro. Apple would then iterate over several releases trying to add different types of advanced app launching and window management, while continuing to add support for devices such as external storage, third-party microphones, etc. These were all supported on Windows in all form factors, including on ARM devices. Still, as all the reviews noted, Apple had a giant head start on the incredibly successful iPad, while Microsoft and Windows had the PC all but locked up. At least for the time being.

If I were to be a bit delusional, I might think that Windows 8 had Apple a bit concerned. That would be crazy since in all the years I worked and competed with Apple I never knew them to care very much at all what Microsoft did outside of supporting the Mac. Instead, I would definitely give Apple credit to sticking with their narrative and strategy. They stood to benefit enormously if they could at once convince their Mac customer base that they also needed an iPad while also convincing the world that the iPad was the future of productivity computing.

As it would turn out, Apple digging in along this line would prove to be extremely good marketing as well. By continuing to define tablets as a separate category and the future while they had a two-year head start, they made our attempt to message a different narrative extremely difficult. Many of the difficulties discussed in the next section relate to Apple’s success at defining the iPad as both distinct from PCs and also the future. That left us little room to have a device that was able to do both. The toaster-refrigerator metaphor only made that clearer.

If we fast-forward, we can see how Apple stuck with this positioning while also making things very difficult for themselves. Given the chaos surrounding iPadOS 16.1 when it came to advancing software and the complexity of the iPad line, including the add-on keyboards, a strong case could be made that Apple has so far mismanaged the opportunity they created. Unit sales remain spectacular but perhaps less as a mainstream computer and more as a specialized device. Time will tell.

During the first week of the release, we had over 1.6M activated testers and easily surpassed what we saw with the incredibly successful Windows 7 beta test. The Windows Store and WinRT notification platform were seeing numbers in the millions as well. We were receiving usage data from these users and were able to analyze what they were experiencing in terms of quality, reliability, and feature usage. This was an incredibly successful wide-scale beta test.

We had months of decelerating bug fixing and a giant matrix of hardware and software compatibility to test. But that paled in comparison to the dramatic change in tone and tenor we faced, suddenly and almost out of the blue.

Where do we start?

On to 106. The Missing Start Menu

“A Review of Windows 8 Beta” by David Pogue, New York Times, February 29, 2012. https://archive.nytimes.com/pogue.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/02/29/a-review-of-the-windows-8-beta/

“Citigroup Positive on Microsoft's Windows 8” via Benzinga.com https://www.benzinga.com/article/2414539

"Does Windows 8 diss the PC?" by Dan Ackerman, CNET, February 29, 2012. https://www.cnet.com/tech/mobile/does-windows-8-diss-the-pc/

Apple earnings transcript, April 24, 2012 via https://finance.yahoo.com/news/apples-ceo-discusses-q2-2012-011004832.html

![Top News Kent Walter / The Windows Blog: Introducing Windows 8 Consumer Preview - Moments ago in Barcelona, we announced the release of Windows 8 Consumer Preview, available to download now for anyone interested in trying it out. We've been hard at work for many months now, and while we still have lots more to do ... More: Edward C. Baig / USA Today: Microsoft unveils Windows 8 Larry Dignan / CNET: Windows 8: Last of the big bang consumer releases? Dan Rowinski / ReadWriteWeb: With Windows 8, Microsoft Learns From the Mobile Revolution Jordan Crook / TechCrunch: Fly Or Die: Windows 8 David Pogue / Pogue's Posts: A Review of the Windows 8 Beta David Goldman / CNNMoney.com: Microsoft releases Windows 8 preview Joe Wilcox / BetaNews: So, what do you think of Windows 8? - I must be candid. Nicholas Kolakowski / Week: Windows 8 Consumer Preview Kicks Off Microsoft's Next Big Push Steven Sinofsky / MSDN Blogs: Running the Consumer Preview: system recommendations Dwight Silverman / blog.chron.com: Windows 8 Consumer Preview: Should you install it? [Updated] Shaylin Clark / WebProNews: Windows 8 Brings A Host Of New Features Eric Savitz / The Tech Trade: Microsoft: Windows 8 Is Here - The Windows 8 start page. Nathan Ingraham / The Verge: Microsoft releases Internet Explorer 10 Platform Preview 5 Carl Franzen / TPM Idea Lab: Windows 8 Consumer Preview Is Here: Initial Reviews Lyle Smith / laptopreviews.com: Windows 8 Consumer Preview Available to Download Peter Pachal / Mashable!: Windows 8 Consumer Preview: The Good, the Bad and the Metro [REVIEW] Ina Fried / AlIThingsD: Microsoft Says Hola to Windows 8 Beta in Barcelona Calob Horton / Pocketables: Windows 8 Consumer Preview officially released, explained, detailed Wilson Rothman / msnbc.com: Windows 8 first look - and first touch Hayley Tsukayama / Washington Post: MC 2012: Windows 8 Consumer Preview available for download Steve Huff / Betabeat: Microsoft Drops Windows 8 Consumer Preview, A 'Reimagined,' Cloud-y, Charmed Windows Microsoft: Microsoft Announces Availability of Windows 8 Consumer Preview Sam Churchill / dailywireless.org: Windows 8 Consumer Preview Anil Erduran / TechNet Blogs: The Windows Consumer Preview and Windows Server 8 Beta Builds are Now Available for Download Computerworld: Microsoft shows Windows on ARM tablet designs Molly McHugh / Digital Trends: Microsoft announces Windows 8 and offers up the consumer preview Nathan Olivarez-Giles / Los Angeles Times: Microsoft releases Windows 8 Consumer Preview for free download MSDN Blogs: Windows Consumer Preview: The Fifth IE10 Platform Preview Reuters: Microsoft releases Windows 8 for public testing Zach Honig / Engadget: Microsoft Windows 8 on 82-inch touchscreen hands-on (video) Allan Swann / Computer Business Review: Microsoft releases free Windows 8 Consumer Preview Brad Linder / Liliputing: Windows 8 Consumer Preview runs well on netbooks (mostly) Zach Epstein / BGR India: Welcome to the post-post-PC era: A review of Microsoft's Windows 8 Consumer Preview Electronista: Microsoft Windows 8 Consumer Preview available to download Brier Dudley / The Seattle Times: Hands-on: Windows 8 Consumer Preview Harry McCracken / Techland: Windows 8 Consumer Preview: One Step Closer to the PC's Future Amit Chowdhry / Pulse2 Technology and Social Media News: Microsoft Unveils Windows 8 Consumer Preview Paul Lilly / HotHardware.com News: At Long Last, Windows 8 Consumer Preview is Available to Download Phone Arena: Windows 8 tablet UI is dominated by gestures Whitson Gordon / Lifehacker: First Look at What's New in Windows 8 John Callaham / Neowin.net: More info on Windows 8 Consumer Preview requirements Mike Halsey MVP / Windows 8 News, Rumors & Tips: Microsoft Release the Windows 8 Consumer Preview Jenna Wortham / Bits: Microsoft Unveils Its Next Operating System, Windows Eric Leamen / Current Editorials: Microsoft's Windows 8 Consumer Preview now available to download E.D. Kain / Social Media: What To Expect From Windows 8 Consumer Preview Cyril Kowaliski / The Tech Report: The Top News Kent Walter / The Windows Blog: Introducing Windows 8 Consumer Preview - Moments ago in Barcelona, we announced the release of Windows 8 Consumer Preview, available to download now for anyone interested in trying it out. We've been hard at work for many months now, and while we still have lots more to do ... More: Edward C. Baig / USA Today: Microsoft unveils Windows 8 Larry Dignan / CNET: Windows 8: Last of the big bang consumer releases? Dan Rowinski / ReadWriteWeb: With Windows 8, Microsoft Learns From the Mobile Revolution Jordan Crook / TechCrunch: Fly Or Die: Windows 8 David Pogue / Pogue's Posts: A Review of the Windows 8 Beta David Goldman / CNNMoney.com: Microsoft releases Windows 8 preview Joe Wilcox / BetaNews: So, what do you think of Windows 8? - I must be candid. Nicholas Kolakowski / Week: Windows 8 Consumer Preview Kicks Off Microsoft's Next Big Push Steven Sinofsky / MSDN Blogs: Running the Consumer Preview: system recommendations Dwight Silverman / blog.chron.com: Windows 8 Consumer Preview: Should you install it? [Updated] Shaylin Clark / WebProNews: Windows 8 Brings A Host Of New Features Eric Savitz / The Tech Trade: Microsoft: Windows 8 Is Here - The Windows 8 start page. Nathan Ingraham / The Verge: Microsoft releases Internet Explorer 10 Platform Preview 5 Carl Franzen / TPM Idea Lab: Windows 8 Consumer Preview Is Here: Initial Reviews Lyle Smith / laptopreviews.com: Windows 8 Consumer Preview Available to Download Peter Pachal / Mashable!: Windows 8 Consumer Preview: The Good, the Bad and the Metro [REVIEW] Ina Fried / AlIThingsD: Microsoft Says Hola to Windows 8 Beta in Barcelona Calob Horton / Pocketables: Windows 8 Consumer Preview officially released, explained, detailed Wilson Rothman / msnbc.com: Windows 8 first look - and first touch Hayley Tsukayama / Washington Post: MC 2012: Windows 8 Consumer Preview available for download Steve Huff / Betabeat: Microsoft Drops Windows 8 Consumer Preview, A 'Reimagined,' Cloud-y, Charmed Windows Microsoft: Microsoft Announces Availability of Windows 8 Consumer Preview Sam Churchill / dailywireless.org: Windows 8 Consumer Preview Anil Erduran / TechNet Blogs: The Windows Consumer Preview and Windows Server 8 Beta Builds are Now Available for Download Computerworld: Microsoft shows Windows on ARM tablet designs Molly McHugh / Digital Trends: Microsoft announces Windows 8 and offers up the consumer preview Nathan Olivarez-Giles / Los Angeles Times: Microsoft releases Windows 8 Consumer Preview for free download MSDN Blogs: Windows Consumer Preview: The Fifth IE10 Platform Preview Reuters: Microsoft releases Windows 8 for public testing Zach Honig / Engadget: Microsoft Windows 8 on 82-inch touchscreen hands-on (video) Allan Swann / Computer Business Review: Microsoft releases free Windows 8 Consumer Preview Brad Linder / Liliputing: Windows 8 Consumer Preview runs well on netbooks (mostly) Zach Epstein / BGR India: Welcome to the post-post-PC era: A review of Microsoft's Windows 8 Consumer Preview Electronista: Microsoft Windows 8 Consumer Preview available to download Brier Dudley / The Seattle Times: Hands-on: Windows 8 Consumer Preview Harry McCracken / Techland: Windows 8 Consumer Preview: One Step Closer to the PC's Future Amit Chowdhry / Pulse2 Technology and Social Media News: Microsoft Unveils Windows 8 Consumer Preview Paul Lilly / HotHardware.com News: At Long Last, Windows 8 Consumer Preview is Available to Download Phone Arena: Windows 8 tablet UI is dominated by gestures Whitson Gordon / Lifehacker: First Look at What's New in Windows 8 John Callaham / Neowin.net: More info on Windows 8 Consumer Preview requirements Mike Halsey MVP / Windows 8 News, Rumors & Tips: Microsoft Release the Windows 8 Consumer Preview Jenna Wortham / Bits: Microsoft Unveils Its Next Operating System, Windows Eric Leamen / Current Editorials: Microsoft's Windows 8 Consumer Preview now available to download E.D. Kain / Social Media: What To Expect From Windows 8 Consumer Preview Cyril Kowaliski / The Tech Report: The](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!-_DA!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ffcd5b078-79da-478e-a4c5-e23ec50af981_1907x2577.png)

One thing I've often wondered about Windows 8 is whether it violated what PJ Hough used to preach about "you can do two things great or three things mediocre" (or something like that). I get the sense in full hindsight that Windows 8 tried to be a) a new Ux paradigm for mobile b) a new app framework for safe/secure/modern c) a platform pivot to empower Office into the future. Clearly the latter didn't happen. Which again in hindsight is because little about Windows 8 helped Office with their highest priorities. Which makes me wonder how much energy spent on (c) caused loss of focus on (a) and (b)?

I'm reminded of a much smaller version of this when the OLE team came to Office with their plans for OLE3. Office's response to the OLE plans was "But you aren't solving any of our highest priority issues". To which OLE replied "But you're our most valuable customer".

There was clearly a disconnect in that relationship and hence OLE2 became "peak OLE" (using your phrasing).

This was a very interesting chapter. As a lifelong Mac user (more or less), I have never been that comfortable with Windows. Everything about it always felt like I was doing things “backwards”. But I was very interested by the boldness of Windows Phone and Windows 8 and their wildly different approach compared to iOS and then-copycat Android. I even installed a Windows 8 beta in Parallels on my Mac. It was a great system, but clearly held back by the lack of Office and the need to fall back to the old Windows 7 desktop for some pretty basic things. I was never tempted to switch, as none of my favorite apps run on Windows, but I as very impressed, and then disappointed when it didn’t pan out.

Windows 8 and WebOS were two UIs that had such a huge impact on the broader market, but didn’t reap the rewards of that. While iOS’s SpringBoard was, until recently, kind of just a modern take to n Windows 3’s Program Manager, Windows Phone and Windows 8 were something truly new.