099. The Magical iPad

"Last time there was this much excitement about a tablet, it had some commandments written on it." — A chuckling Steve Jobs quoting The Wall Street Journal (Martin Peers, 12/30/09)

The launch of an innovative new product is always exciting. The launch of an innovate new product from a competitor is even more exciting. But what is it like when your main competitor launches an innovative new product at a moment of your own fundamental strategic weakness? That’s what it was like when the iPad launched on January 27, 2010. On the heels of the successful Windows 7 launch during a time when Microsoft was behind on mobile and all things internet and in the midst of planning Windows 8, Apple launched the iPad. Many would view the iPad (and slates and tablets) as “consumption devices.” Steve Jobs and the glowing press that followed the launch viewed the iPad as a fundamental improvement in computing. Whatever your view, it was a huge deal.

This post is free for all email subscribers. Please consider signing up so you don’t miss the remaining posts on Windows 8 and for access to all the back issues.

Back to 098. A Sea of Worry at the Consumer Electronics Show

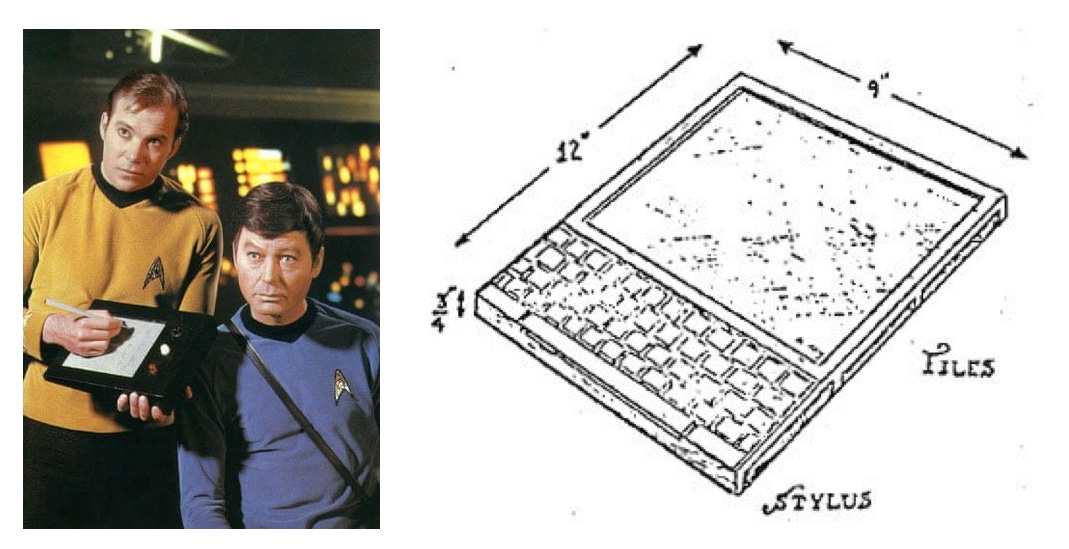

For months, BillG and a small group of Microsoft executives believed Apple was going to release a tablet computer. It had been rumored for more than a decade. Originally, tablet shaped computers traced their roots to legendary Alan Kay’s 1960’s Dynabook, plus there was that one on Star Trek. There’s a long-held belief among Trekkers that all Star Trek tech will eventually be realized. By 2010, Microsoft had a decade plus of Tablet PC experience, mixed as it was. With Windows 7 we brought all the tablet features into the main product instead of a special SKU, so every version of Windows could run effectively on any PC with tablet hardware, such as a pen and touch screen. What was different about the Apple rumors in 2010? What made us more nervous? Why, this time, did we believe these rumors about a company for which predictions had always been wrong? No one had predicted the iPhone with any specificity.

Microsoft and partners had invested a huge amount of time, energy, and innovation capital in the Tablet PC, but it was not breaking through the way many hoped, such as how we visualized it in the Office Center for Information Work. The devices for sale were expensive, heavy, underpowered, had relatively poor battery life, and inconsistent quality. Beyond the built-in applications, OneNote from Office, and a few industry-specific applications pushed through by Microsoft’s evangelism efforts, there was little software that leveraged the pen and tablet. Many, myself included, were decreasingly enthused. BillG, however, was tireless in his advocacy of the device—and the fact that Apple might make one, and whatever magic Steve Jobs could bestow upon it, only served to juice the competition between companies and founder/CEOs. BillG remained hardcore and optimistic about the pen for productivity and a keyboard-less device for on-screen reading and annotation.

To BillG a PC running Windows that was shaped like a slate or tablet seemed inevitable. For many of the boomer computer science era, the fascination of handwriting and computing on a slate had been a part of the narrative from the start. Over the past 30 years, few of the technical problems had been solved, particularly handwriting but also battery life and weight. Then came the iPhone and multitouch.

That Apple would build such a PC was more credible than ever because of their phone, though by Microsoft measures the iPhone still lacked a stylus for pen input, something Steve Jobs openly mocked on several occasions. The possibility made us nervous and anxious, especially knowing Windows 8 was underway.

Collectively, and without hesitation, many believed Apple would turn the Mac into a tablet. Apple would add pen and touch support to the Mac software, creating a business computer with all the capabilities of Office and other third-party software, and the power of tablet computing. The thinking was that a convertible device made a ton of sense since that allowed for productivity and consumption in one device. Plus, techies love convertible devices of all kinds.

There were senior executives at Microsoft with very close ties to Apple who were certain of Apple’s plans and relayed those to Bill. Bill would almost gleefully share what he “knew” to be the case, using such G-2 to prod groups into seeing the opportunity for his much-loved tablet strategy.

There were debates consuming online forums—rumors rooted in the Asian supply chain as to what sort of screens and chips Apple might be purchasing for the rumored product. Some thought there would be a “big iPod” and still others thought Apple would develop a product tailored to books, like the two-year-old Amazon Kindle. In other words, no one had a clue and people were making stuff up. Some were even calling it the iPad, not because there was a leak or anything but because it made more sense than iTablet or iSlate, and because at one point (in the late 1990s!) Microsoft had something in R&D called WinPad. The industry had not even settled on the nomenclature for the form factor, cycling among tablet, slate, pad, MID, convertible, and so on.

This CNN story by Kristi Lu Stout from January 2010 detailed the history of tablet computers, including Apple’s own past going way back to before Macintosh.

At least in the months prior to launch, zero people, to my knowledge, thought that Apple had in mind a completely novel approach. An aspect of disruptive innovation is how incumbents project their views of strategy on to competitors without fully considering the context in which competitors work. As much as Microsoft primarily considered Apple to be the Mac company that happened to stumble into music players and then phones, by 2010 Apple had already pinned its future and entire product development efforts to iPhone and what was still called the iPhone OS, which was based on OS X, the Mac OS, but modernized in significant ways.

On January 27, 2010, at a special press event billed as "Come see our latest creation," Steve Jobs unveiled the iPad. I followed the happenings on the live blogs. This was one of the first Apple special events used to launch products, as the previous 2009 MacWorld was the last one in which Apple participated.

The event took place starting with the reminder that Apple had become the world’s largest mobile device company, followed by Steve Jobs quoting, with a bit of a chuckle, an article from December in The Wall Street Journal, “The last time there was this much excitement about a tablet, it had some commandments written on it.”

As part of his build-up to introducing the iPad, he pointed out that in defining a new category, a tablet needed to be better at some important things, better than a phone or a laptop. It needed to be better at browsing, email, photos, video, music, games, and eBooks. Basically, everything other than Office and professional software it seemed to me—though this would come to be known as “creation” or “productivity” by detractors who would posit that the iPad was a “consumption” device. As we will see, the Microsoft Office team was already hard at work at bringing Office apps to the iPad.

The launch event deliberately touted “latest creation” in the invitations, which I always thought was a bow to creativity as a key function. What many pundits and especially techies failed to appreciate was that productivity and creativity had new, broader, definitions with the breadth of usage of computers as smartphones. Productivity and creativity were no longer the sole province of Word, Excel, Photoshop, and Visual Studio. The most used application for creating was email and it was already a natural on the iPhone, only soon to be replaced by messaging that was even more natural.

As the presentation continued Jobs delivered his first gut punch to the PC ecosystem in describing what such a device might be, as he set up a contrast for what the new category should do relative to netbooks.

“Some people have thought that that’s a Netbook.” (The audience joined in a round of laughter.) Then he said, “The problem is…Netbooks aren’t better at anything…They’re slow. They have low quality displays…and they run clunky old PC software…. They’re just cheap laptops. (more laughter)”

Ouch. He was slamming the darling of the PC industry. Hard.

The real problem was not only that was he right, but that consumers had come to the same conclusion. Sales of Netbooks had already begun their plunge to rounding error.

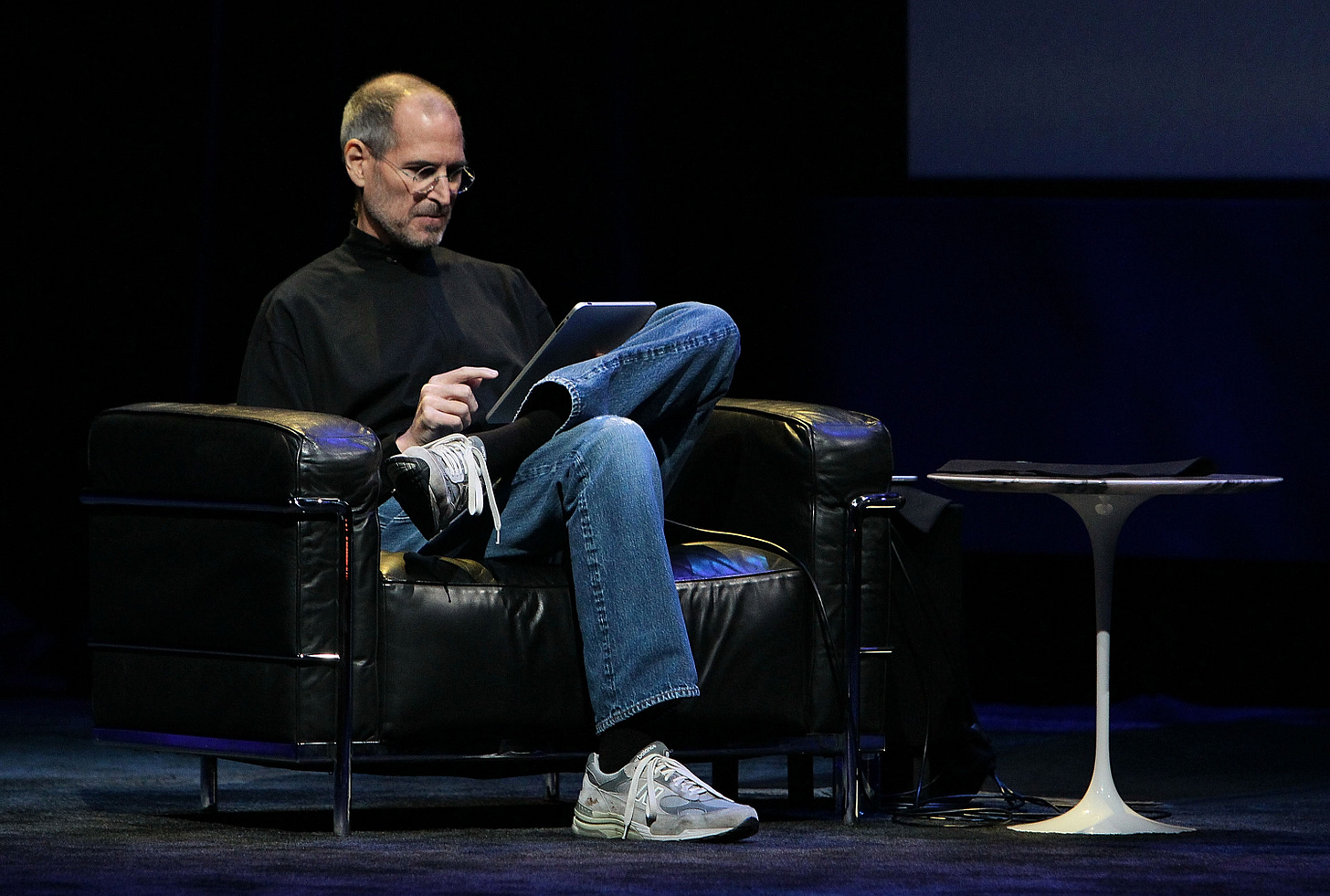

Jobs unveiled the iPad, proudly. Sitting in a le Corbusier chair, he showed the “extraordinary” things his new device did, from browsing to email to photos and videos and more. The real kicker was that it achieved 10 hours of battery life—a flight from San Francisco to Tokyo watching video on one charge, recharged using your iPhone cable. It also achieved more than 30 days of standby power and like a phone, it also remained connected to the network in standby, reliably downloading emails and receiving notifications. This type of battery management was something the PC architecture struggled endlessly to achieve. The introduction concluded with a series of guests showing specially designed iPad apps in the 18 months old App Store, now with over 140,000 apps.

The eBook-specific apps really got under our skin given how much this had been the focus of many efforts over many years. Being a voracious reader, BillG championed eBooks for the longest time. Teams developed formats and evangelized the concept to publishers. Still Microsoft lacked a device to comfortably read books. Then there was Steve Jobs reclined on an iconic chair.

Games were the icing on the cake of despair given Microsoft’s efforts on both the Xbox and PC.

But there was no pen! No stylus! Surely, it was doomed to be a consumption device.

Then they showed a paint program that could be used with the touch of a finger. They were just getting started.

There was no productivity! Doomed, for sure. Then they showed updated versions of the iWork suite for the iPad. The word processor, spreadsheet, and presentations package for the Mac had been rewritten and tuned specifically to work with touch on the iPad. Apple even intended to charge for them, though this would later change. Those tools had already been stomped by Mac Office, but they became unique on this unique device. The ever-increasing quality of the tools, particularly Keynote for presentations, quietly became a favorite among the Mac set in Silicon Valley.

All these apps being shown were available in the App Store. They were curated and vetted by Apple, free from viruses, bad behavior, and battery draining features.

Rounding out the demonstration was the fact that the iPad synchronized all the settings, documents, and content purchased with iTunes with a cloud service. This was still early in Apple’s confused journey to what became known as iCloud, but as anyone who tried to sync between a phone and a PC then learned, that it worked at all was an achievement.

The iPad also came with an optional cellular modem built in—on a PC one would need a USB dongle costing a couple hundred dollars and an elaborate software stack that barely worked, plus a monthly $60 fee. On the iPad, there was an unlimited data plan from AT&T for $29.99. Apple and AT&T also made it possible to activate the iPad without going to the store or calling AT&T. Minor, perhaps, but this is the kind of industry-moving innovation Apple almost never gets credit for achieving what was impossible to do uniformly on the PC. Even today, mobile connectivity on a PC is at best a headache.

The pricing was also innovative. Apple had previously been called out as a high-priced technology vendor and for a lack of an appropriate low-price product response to Netbooks. There was no doubt the iPad would be portrayed as expensive. In fact, after drawing out sharing the price, Jobs announced it would start at $499, a shockingly low price point which was close enough to Netbook territory. The price went to $829 fully loaded with storage and 3G, which remained the same as many loaded Netbooks. The price was hardly OLPC but it was low, with $499 viewed as a magic price at retail.

The product would be available in all configurations in 90 days worldwide.

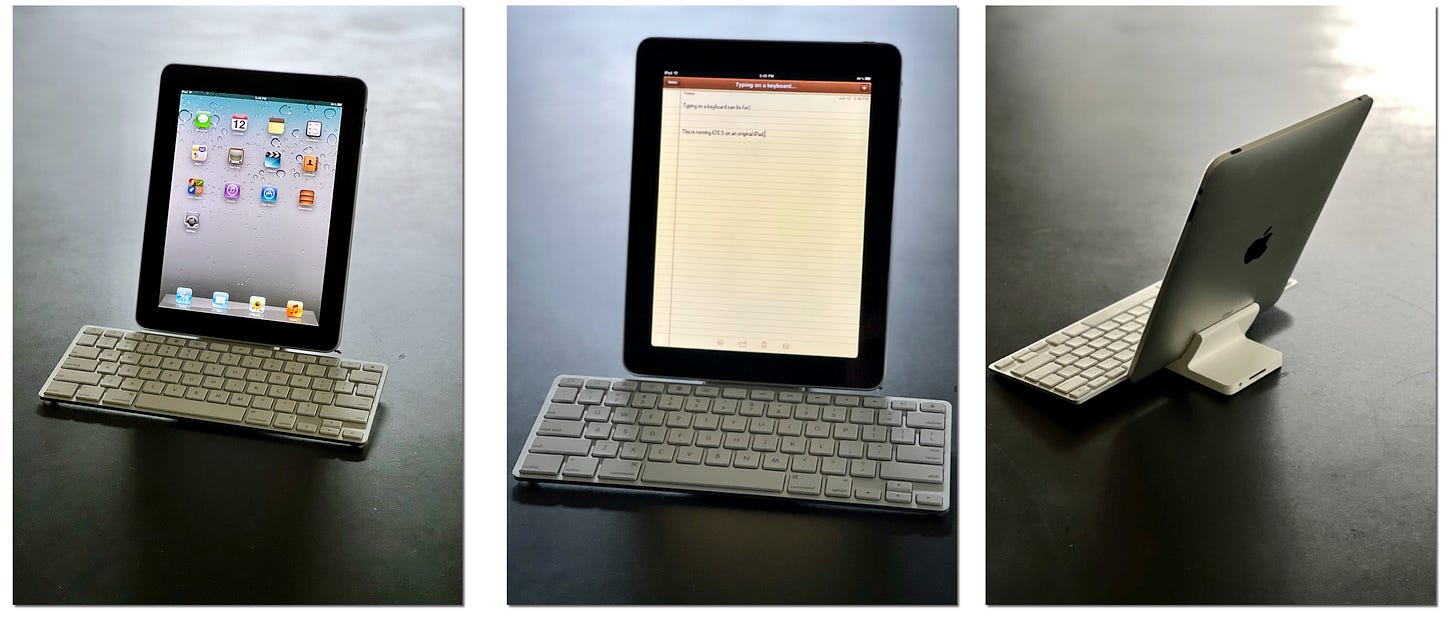

I promptly ordered mine. I also ordered the keyboard dock described below.

It was all so painful. Each time Jobs said “magical” I thought “painful.”

There were so many things iPad hardware did that the PC could not do or had been trying and failing to do for so long that suddenly made all the difference: incredibly thin and light, all-day battery life, wonderful display, low-latency touch screen, 3G connectivity, multiple sensors, cameras, synchronizing settings and cloud storage, an App Store, and so much more. My favorite mind-blowing example was the ability to easily rotate the screen from portrait to landscape without any user interface action. It just happened naturally. At a meeting with Intel, the head of mobile products took an iPad out and spun it in the air yelling at me with his thick Israeli accent “when will Windows be able to rotate the screen like this?!” My head hurt. All of this made possible because the iPad built on the iPhone. Yes, it was a big phone, but it proved to be so much more. It had so much potential because of the software.

It also had productivity software, and, to finally rub in the point, the first iPad even had a desktop docking station with a keyboard attached. Jobs didn’t need to address the complexity of adding a keyboard, but having a keyboard that actually worked without the touch screen keyboard popping up and getting in the way was an important technical breakthrough and also one rooted in using the iPhone adapted OS X operating system kernel while also using a new platform for application software. This was one of many subtle points we picked up on that showed the foresight of the underlying strategy. It was obvious the keyboard dock was an “objection handler” and not a serious effort, but it motivated an ecosystem of keyboard folios and cases for the iPad until Apple itself finally introduced innovative keyboard covers.

The conclusion of the presentation reminded everyone that 75 million buyers of iPhones and touch iPods already knew how to use the iPad. There was no doubt from that moment that the future of the portable computer for home or work was an iPad or iPad-like device—the only questions were how long it would take to happen and how much Windows could thrive on simply supporting legacy behavior.

It was, as Jobs said, “The most advanced technology in a magical and revolutionary device at an unbelievable price.”

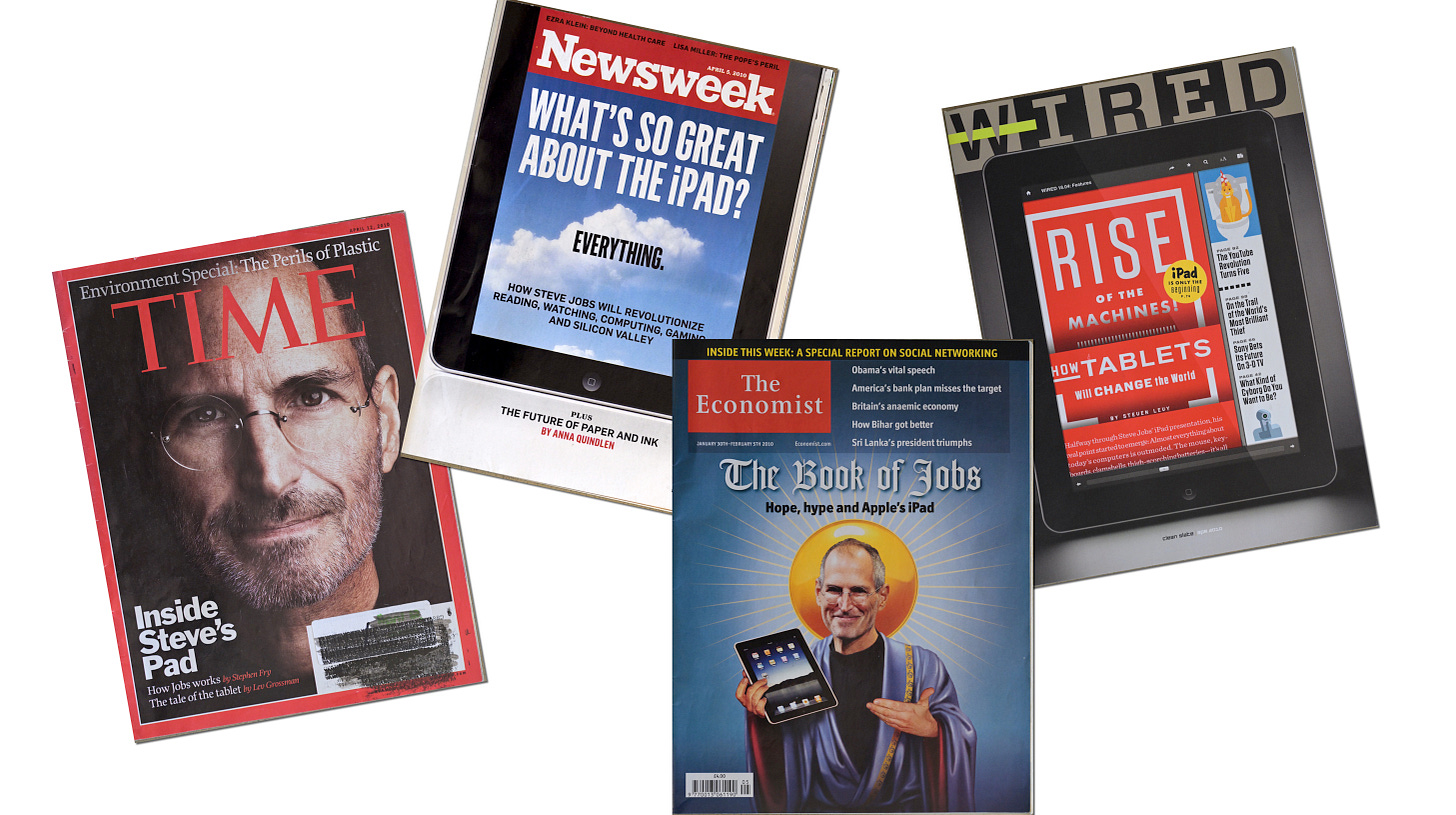

The international magazine coverage of the iPad launch was mind-blowing. It was pure Steve Jobs, the genius. The Economist cover featured Steve Jobs as a Messiah-like character with biblical text over his head “The Book of Jobs: Hope, Hype and Apple’s iPad” as he held the iPad tablet not unlike Moses.1 Time, Newsweek, Wired, and just about every tech publication that still printed on paper did a cover story. The global coverage squarely landed the message that the iPad was the future of computing.

From the PC tech press, the announcement drew skepticism. The iPad was, marginally, more expensive than dying Netbooks. It lacked a full-size keyboard for proper productivity. It didn’t have a convenient USB slot to transfer photos or files (that was the most common way of sharing files at the time). The use of adjectives like “full” or “proper” or “truly” peppered the reviews when talking about productivity. This was all strikingly familiar as it sounded just like the kind of feedback the MacBook Air received from these same people.

There was endless, and tiresome, commentary on how there could not be productivity without a mouse, a desktop, and overlapping windows (generously called multi-tasking which is technically a misnomer.) The irony was always lost on the person commenting—there was a time when the PC did not have a mouse and, in fact, the introduction of the mouse was viewed as a gimmick or a toy entirely counter to productivity. Or the fact that for most of the Windows history, the vast majority of users ran with one application visible at a time just like on the iPad. I collected a series of articles from the 1980s criticizing the mouse. Fast forward to 2010, replace mouse with touch, and these read exactly the same. It was as if we had not spent the past three years debating whether one could use a smartphone with only a touchscreen.

Also, there were no files. How could anyone be productive without files? The iPad turned apps using a cloud into the primary way to create and share, not files and attachments. Apple would later add a Files app. Kids today have no idea what files are.

When they weren’t making fun of the name “iPad” many were quick to mock the whole concept of an iPad as a simply puffed-up iPhone. Ironically, the mid-2010 iPhone was still a tiny 3.5” screen; it would not be until late 2014 when Apple would relent and introduce a larger screen iPhone and a year later would introduce a 12.9” iPad. Apple in no way saw the iPad as simply a larger iPhone.

Walt Mossberg set different tone in with his review. “Laptop Killer? Pretty Close—iPad Is a 'Game Changer' That Makes Browsing And Video a Pleasure; Challenge to the Mouse.” Among the positive commentary, Mossberg said of the iPad Pages word processor, “This is a serious content creation app that should help the iPad compete with laptops and can import Microsoft Office files,” and, “As I got deeper into it, I found the iPad a pleasure to use, and had less and less interest in cracking open my heavier ThinkPad or MacBook. I probably used the laptops about 20 percent as often as normal.” He concluded with a reminder that this was going to be a difficult journey. “Only time will tell if it’s a real challenger to the laptop and Netbook.”2

Apple sold about 20 million iPads in the first year (2010 to 2011) while we were building Windows 8. As it would happen, 2011 was the all-time high-water mark (through this writing) for PC sales at 365 million units, or about 180-200 million laptops. The resulting iPad sales were not a blip or a fad in the portable computing world—10% of worldwide laptop sales in the first year! In contrast, Netbook sales fell off a cliff and all but vanished as quickly as they appeared. Each quarterly PC sales report was skittish as sales growth was slowing. At first the blame was put on the economy, or maybe it was a shortage of hard drives or the lack of excitement from Windows. It would be a while before the PC industry absorbed the impact of phones and tablets and later Google ChromeBooks. There was a brief respite during the first year of the global pandemic and work-from-home, but that too quickly subsided. It is expected that 2022 PC sales (including Google Chromebooks) will be about 300M units.

The iPad and iPhone were arguably the most existential challenges Microsoft had ever faced. While the industry focus and Apple’s business were on the devices, the risk came from the redefinition of operating system capabilities and software development and distribution. Apple had created a complete platform and ecosystem for a new and larger market. This platform came not at a time of great strength for Microsoft, but a time when we were on our heels strategically fighting for our relevancy. The Windows platform had been overrun by the browser, including the recent entry from Google that would soon eclipse Internet Explorer as well as the recently announced ChromeOS. PC OEMs were in rough shape financially and had an uncertain future. Windows Server, as well as it had been doing, had failed to achieve leadership beyond the (large) enterprise market. Linux and open source dominated the public internet. Amazon Web Services and cloud computing consumed the energies of academia and start-ups. Windows Phone 7 had not yet shipped and Windows Phone 6.5 was being trounced by Apple from above and Android from below. Even hits from Xbox to SQL Server were not actually winning in their category but were distant second place.

If ever “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” applied to a company, the summer of 2010 was it for Microsoft. When it came to financial success Microsoft was in a fantastic position, but strategically and in “thought leadership” we were in a weak position.

Perhaps Microsoft could have made better bets earlier and we squandered what could have been a potential lead? In October 2011, almost two years since the iPad was available, I received an email from a corporate vice president of public relations. He relayed a message from a reporter asking about an unreleased Microsoft tablet with the codename Courier. The reporter wanted to know, “Why did Sinofsky kill it?” According to the reporter, the Courier project had been going on since before the iPad was released (this was important) and it was only just now, 18 months after the iPad was available, it became clear that Sinofsky killed it.

Oh no, they found out, I thought. Crap.

The problem was that I had never seen this project. I’d hardly heard of it other than rumors of just another random project in E&D operating under the radar that had been cancelled more than a year earlier. There was a small story in Gizmodo tech blog when the project, which was a design sketch/prototype was cancelled shortly after the iPad announcement in April 2010, “Microsoft Cancels Innovative Courier Tablet Project”:

It is a pity. Courier was one of the most innovative concepts out of Redmond in quite some time. But what we loved about Courier was the interface and the thinking behind it-not necessarily its custom operating system.3

Courier was developed in E&D, Entertainment and Devices division, where Xbox and Zune were developed. It was, apparently, a design for a dual-screen, pen-based tablet. A conceptual video rendering of the device leaked, and the internet was very excited. It looked to be the dream device to techies—it had two screens and folded like a book! As fascinating as it was, all anyone, myself included as far as I knew, had to judge it by was an animation. The first time I saw the animation was on the internet just before the project was cancelled.

That video leaked (by whom?) two months prior to the iPad announcement during the height of tablet rumors even before the CES show with Windows 7 tablets and early Android tablets. Gizmodo, who above praised it as one of the most innovative concepts coming out of Redmond, described the Courier interface relative to their favorite interpretation (or “what everyone expects”) of Apple tablet rumors:

The Courier user experience presented here is almost the exact opposite of what everyone expects the Apple tablet to be, a kung fu eagle claw to Apple's tiger style. It's complex: Two screens, a mashup of a pen-dominated interface with several types of multitouch finger gestures, and multiple graphically complex themes, modes and applications. (Our favorite UI bit? The hinge doubles as a "pocket" to hold items you want move from one page to another.) Microsoft's tablet heritage is digital ink-oriented, and this interface, while unlike anything we've seen before, clearly draws from that, its work with the Surface touch computer [the tabletop described earlier] and even the Zune HD.4

In hindsight, one just knows that Apple got a huge kick out of this device and the quasi-strategic leak from the team.

More importantly, I had to pick up the pieces with the PC OEMs who read the articles about this device and wondered if Microsoft was competing with them or undercutting their own efforts at new Windows 7 tablets. In the leadup to the first CES with Windows 7 and our work on touch and tablets, trying to generate support across the ecosystem, this kind of leak was devastating. Aside from the appearance of hiding important details from partners, it looked like one part of Microsoft was competing with our biggest customers or worse that the Windows team was part of the duplicity. In his CES 2010 keynote, SteveB had to call out and bring special visibility to a new tablet from HP just to smooth over the relationship due to the Courier leak months earlier. There was non-stop scrambling from the time of the Gizmodo leak until he stepped off stage. HP, as the largest OEM, was (and remains) directly responsible for billions in Windows revenue, and thus profit. Months later, HP bought Palm and its WebOS software for $1.2 billion with every intent of creating a tablet with its own operating system. It would not be unreasonable to conclude that HP pursued Palm because of the Courier project even with the history of OS development at HP.5 Our OEM partners thought we were bad partners.

The group of Microsoft influencers on the internal email discussion group LITEBULB thought we were foolish for cancelling what would certainly have been the next killer device. One person said, on a long discussion thread contrasting Courier with money-losing Bing and Xbox, “In my view, our apparent unwillingness to lose money on a few innovative, sexy products that people drool over is part of the reason we are losing the public perception battle to Apple and Google.”

Courier became a shorthand or meme for incompetent management at Microsoft. Given the climate around the company and a decade of a relatively flat stock price, such internal discussions contributed to a growing narrative of the death-of-innovation at Microsoft. For so many reasons it was readily apparent even if materialized as a real PC, Courier would have been as doomed as all the Tablet PC products before it, and even more so because of the dual-screen approach. My own team mostly thought I was foolish for not even knowing about the existence of Courier.

I looked unaware or dumb, or both, and along with all the powers at Microsoft had stifled innovation.

We thought this story was over and then more than two years after that leak we received the inbound indicating I was the culprit and the reporter awaited comment. When the video of the leak first surfaced, I sent an email trying to understand if the Courier project was related to Windows 7. Was it for sale? What version of Windows 7 was it running? Did OEMs know? I became concerned that there was a modified source tree of Windows 7 floating around and how would that be released and supported? Was this another Tablet PC or Media Center code fork and potential mess? I was told it would run Windows 7, but heavily modified. Xbox was originally the Windows source code so now knowing the team I became concerned that playbook would be used. We had just cleaned all this up with the release of Windows 7, but this new situation could turn into a real mess. We just spent three years on Windows source code and sustaining engineering hygiene, so this better not take us back from where we came, I opined. It was messy, but as it turned out the budgeting and management processes within E&D led to the demise of Courier and had nothing to do with the concerns I expressed after the fact.

My reaction was to just tell the reporter we would go on record that I did not have any role in “murdering” the Courier project and had no knowledge of it until I saw the leaked video. I said as much in email to the communications team. There was no shaking the reporter who was certain of his sources and simply concluded this was some sort of misdirection from me and Microsoft. Whatever. A decade later whenever a dual screen device shows up in the market the Windows fans return to Courier and remark “what could have been” and that acts like an SEO (search engine optimization) effort to join my name with killing innovation.

We looked bad from every direction: internal innovation watchdogs, OEM partners, as an executive staff lacking a coherent strategy, and most of all with our own Windows team. The innovation or lack thereof narrative at Microsoft was dutifully fed by cancelling this project, which given our experience with Windows 7 would of course not have been successful. There were so many problems. The entire experience shows the problem with demos, leaks, press sources, and what it is like to try to do (or not do) new things in the context of a broader narrative.

It is a decade since Courier was cancelled and people still hope to bring back this project and many still see it as symbolic of the company’s tendency to stifle innovative projects. Surface released the Microsoft Surface Duo device, running a modified Google Android as a somewhat puzzling approach. Courier routinely shows up on lists of innovative projects killed by mismanagement. There’s some irony in that latter view given Microsoft’s penchant for continuing to pursue products long after they have failed to achieve critical mass, well-beyond the requisite three versions.

The debates within the team about the iPad were there. Would it replace or augment a laptop? Was it a substitute for a PC and users continue to do what they did on a PC, or would people use it as an alternative to do new things in new ways? Would developers build apps specific for the larger iPad screen? Would it ultimately be limited to consumption as many predicted or become a creative and productive tool? Would third-party developers optimize apps for the iPad? Would PC OEMs make a good tablet with the software we would design, or not? This last question was critical.

Amazingly, these debates continue today even with something like a half billion active iPads. The convergence of today’s Apple Silicon Mac and iPad make the debate either more interesting or exceedingly moot.

Back in the realm of what the team could control and execute, we began planning Windows 8 in the Fall of 2009. We saw the disappointments at the Consumer Electronics Show followed by the surprise of the iPad announcement. Our plans came together in the Spring of 2010. For the new Windows team, it was a magical planning effort.

On to 100. A Daring and Bold Vision

What did you think of the iPad?

Also, an Economist Oxford comma.

Wall Street Journal. Mossberg, W. S. (2010, Apr 01). Laptop killer? pretty close — iPad is a 'game changer' that makes browsing and video a pleasure; challenge to the mouse

“Microsoft Cancels Innovative Courier Tablet Project”, Gizmodo 4/29/2010, https://gizmodo.com/microsoft-cancels-innovative-courier-tablet-project-5527442

“Courier: First Details of Microsoft's Secret Tablet”, Gizmodo, 9/22/09 https://gizmodo.com/courier-first-details-of-microsofts-secret-tablet-5365299

In the 1980s during the early days of Windows, HP had its own windowing system built on top of Windows. It was called HP NewWave and was the source of much consternation at Microsoft and a bit of legal back and forth with HP.

We wrote software for Tablet PC when they first launched in the early 2000s. I was in love with the form factor. We even bundled with Viewsonic’s tablets and had a couple around the office. In 2007 or 8, after it was way too slow to run Windows, I installed Linux on it and figured out how to get pdfs and ebooks running. Worked reasonably well but was a brick of a device and the battery was going so didn’t last long.

When the iPhone launched we released a version of our software for it. We did okay but the market was a mess. Novelty apps did better than productivity apps. For iPad, I had a friend who knew a guy in developer relations at Apple and my friend recommended us. Apple was looking for products they could promote that didn’t have an iPad version already. So last minute after announcing but before launch a couple of us went to Cupertino to make sure our software ran on the devices well.

That was amazing. 14 page nondisclosure agreement then escorted us to a room with brown paper over the windows. We worked on iPads tethered to the desk and anytime we ran into trouble they called in the developer who literally wrote the code we were struggling with. Just amazing experience!

We weren’t featured in retail or on stage but did get featured in the App Store a few times, the only time that ever really happened for us, and was a finance app of the year in 2011 (I think). That was the peak of financial success on iOS for us as well. Just brutal.

While I know some made lots of money on Apple’s devices, we did significantly better on Palm and Windows Mobile in late 1990s/early 2000s, honestly. More focused products on business customers and reasonable software prices.

My biggest regret at this time was not realizing how quickly iPad sales grew. I assumed a more traditional slow growth curve, which in my mind gave us more time to plan and execute our response. Netbooks showed the large scope of the desire for computing at some other form factor and strongly implied there was a lot of demand. I was too enmeshed in the PC ecosystem thinking.

There are a lot of strategy angles on this: How Micrsoft's focus on writing and productivity created a blind spot and how Microsoft's poor relationships in the Independent Hardware Vendor (IHV) community (the companies that make components of PCs, like touch screens) caused a miss in understanding how well capacitive touch was working.