098. A Sea of Worry at the Consumer Electronics Show

“Windows, in all form factors, needs to be the best platform and experience to consume the internet while enabling ISVs and IHVs to build the software and hardware to do that.”—Team meeting 1/27/10

The planning for Windows 8 was moving right along. But something wasn’t right as we wrapped up Windows 7 activities at CES 2010. It was looking more and more like the plans and the way the ecosystem might rally around them would yield a watered-down result—it would be Windows and a bunch of features, or perhaps irreconcilable bloat. The way the ecosystem responded to touch support in Windows 7 concerned me. How do we avoid the risk of a plan that did too much yet not enough? Oh, and Apple scheduled a “Special Event” for January 27, 2010, just weeks after a concerning CES.

Back to 097. A Plan for a Changing World [Ch. XIV]

In early January 2010, I was walking around the show floor at CES the evening before opening day as I had routinely done over the years. CES 2010 was a mad rush to build a giant city of 2,500 booths only to be torn down in 4 days. This walk-through gave me a good feel for the booths and placement of demonstrations. It was just two months after the launch of Windows 7. Walking around I made a list of the key OEM booths to scope out first thing in the morning. It wasn’t scientific but visiting a booth had always been an interesting barometer and sanity check for me compared to in-person executive briefings. Later in the week I would systematically walk most of the show and write a detailed report. The next morning, along with the giant crowds, I made my way through a few dozen booths with the latest Designed for Windows 7 PCs mixed in among the onslaught of 3D-television controlled by waving your hands which garnered much of the show’s buzz.

The introduction of touch screens was a major push for Windows 7 and there was genuine excitement among the OEMs to offer touch as an option, though few, okay none, thought it would be a broadly accepted choice. Touch added significantly to the price. With two relatively small suppliers for the hardware, OEMs were not anxious to make a bet across their product line. TReller, the new CMO and CFO for Windows, made a good decision to provide strategic capital to one component maker to ensure Dell would make such a bet.

There were touch models from most every PC maker, but they were expensive—most were more than $2,500 when the typical laptop was sub-$1,000. For the OEMs this was by design. If a buyer wanted touch there was an opportunity to sell a high-end, high-margin, low-volume device. OEMs had been telling us for months that this was going to be the case, but it was still disappointing.

Taking advantage of Windows 7, and wholeheartedly, were a sea of Windows 7 “slates” all based on the same design from the combination of Intel and Pegatron, an ODM. These slates were essentially netbooks without keyboards. They fit the new Intel definition previously described—MID or mobile internet device. They were theoretically built as consumption-oriented companions to a PC. They were shown reading online books, listening to music, and watching movies, though not particularly high resolution or streaming given the meager hardware capabilities. All of them were relatively small and low-resolution screens. To further emphasize the Intel perspective, they also launched AppUp for Windows XP and Windows 7, a developer program and early content store designed to support rights management and in-app purchase as one might use for books and games.

The buzziest slate was from Lenovo, not a product announcement, but a prototype model kept behind glass at the private Lenovo booth located in a Venetian Hotel restaurant. The “hybrid slate” Lenovo U1 was a 11” notebook that could also be separated from the keyboard and used as both a laptop and a slate. As a laptop, the Windows 7 PC used a low-power Intel chipset, a notch slightly above a netbook. Detached as a slate, the device ran a custom operating system they named Lenovo Skylight based on Linux running on a Qualcomm Snapdragon chipset. The combination weighed almost 4lbs. The Linux tablet separated from the Windows-based keyboard PC somewhat like the saucer section of the Starship Enterprise separated from the main ship. Lenovo built software to sync some small amount of activity between the two built-in computers, such as synchronizing bookmarks and some files. Economically, two complete computers would not be the ideal way to go, bringing the cost to $1000. Strategically for Microsoft this was irritating.

Nvidia, primarily known for its graphics cards used by gamers, was always an interesting booth. Nvidia was really struggling through the recession and would finish 2010 with revenue of $3.3 billion and a loss of $60 million.1 As it would turn out it was also a transformative year for the company, and for one of the most legendary founders in all of the PC era, Jensen Huang. To put Nvidia in context, my very first meeting with Intel when I joined the Windows team in 2006 was about graphics, because of the Vista Capable fiasco. Intel was digging their heels in favoring integrated graphics and was not at all worried about how their capabilities were so far behind what Nvidia and ATI, another graphics card maker, were delivering, which Intel viewed as mostly about games. The rub was that AMD, Intel’s archrival, had just acquired ATI for $5.4 billion making a huge bet on discrete (non-integrated) graphics, which was what Nvidia focused on. Intel seemed to believe that the whole issue of graphics would go away as OEMs would simply accept inferior graphics from Intel because it was cheaper and easier while Intel improved integrated graphics over time, albeit slowly. A classic bundling strategy of “a tie is a win” that would turn out to be fatal for Intel and an enormous opportunity for ATI/AMD, Nvidia, and Apple. Intel could have acquired Nvidia at the time for perhaps $10-12B if that was at all possible.

In their booth Nvidia was showing off how they could add their graphics capabilities to the Intel ATOM processor and dramatically speed it up. Recall, ATOM chips struggled to even run full screen video at netbook screen resolutions. With Nvidia ION it was possible to run flawless HD video. Nvidia made this all clear in a “Netbook Nutrition Facts” label that they affixed to netbooks running Nvidia graphics. This was a shot across the bow at Intel, but Nvidia had an uphill battle to unseat bundled graphics from Intel. Nevertheless, we were acutely aware of the strong technical merits of Nvidia’s approach, Jensen’s incredible drive, and the needs of Windows customers. This will prove critically important in the next chapter as we further work on non-Intel processors.

More disappointing was how the OEMs chose to demonstrate touch capabilities in Windows 7. We provided OEMs with a suite of touch-centric applications, such as those demonstrated a year earlier—mapping, games, screen savers, and drawing, for example. We even named it Windows Touch Pack. The OEMs wanted to differentiate their touch PCs with different software and viewed the Touch Pack we provided as lame. Touch had become wildly popular in such a short time because of the iPhone, and the iPhone was a consumer device used for social interaction, consumption of media, and games.

With that frame of reference, the OEMs wanted to show scenarios that were more like an iPhone. The OEMs were going to do what they did, which was to create unique software to show off their PCs. This is just what many in the industry called crapware or, as Walt Mossberg coined in his column, craplets.2 To the OEMs this was a value add and important differentiation. Worst of all, there was no interest from independent software makers who had dedicated few, if any, resources to Win32 product updates, let alone updates specific to touch that was exclusive to the new Windows 7. We never intended to support Windows 7 touch on earlier versions of Windows—something developers ask of every new Windows API. This compatibility technique we often relied on but was a key contributor to Windows PC fragility and flakiness, also referred to colloquially as DLL Hell as previously described.

The overall result: Windows 7 provided no impetus for third party-developers, and we failed to muster meaningful third-party support for any new features, including touch.

What I saw was a series of new OEM apps taking a common approach. These apps could be called shells in typical Microsoft vernacular, an app for launching other apps—the Start menu, taskbar, and file explorer in Windows constitute the shell. In this case, these new shells were usually full-screen apps that had big buttons across the top to launch different programs: Browsing, Video, Music, Photos, and YouTube. These touch-friendly shells did not do much other than launch a program for each scenario, the browser, or simply a file explorer. For example, if Music was chosen then a music player, created by the OEM or chosen because of a payment for placement, would launch to play music files stored on or downloaded to a PC. The use of large touch buttons was thought to give the PC user interface a consumer feel. The browser used part of Internet Explorer but not the whole thing, just the HTML rendering component; for example, it did not include Favorites or Bookmarks usually considered part of a browser. This software, as well intentioned as it was, would fall in the crapware category. This was expected, but still disappointing.

In booths with mainstream laptops we were offered a glimpse into the changing customer views of what made a good laptop. The Windows 7 launch was just a short time ago, so most laptops had incremental updates, primarily with the new version of Windows and perhaps a slight bump in specs. Some show attendees picked up the laptops and grimaced at the weight and thickness—these machines were hardly slick. It had been two full years since the introduction of the MacBook Air and the PC industry still did not have a mainstream Windows PC that fit in the famous yellow envelope wielded on stage by Steve Jobs. The prevalence of Wi-Fi in hotels and workplaces had changed the view that a work PC needed all the legacy ports present on Windows computers, and the fear of dongles had faded. Most every Windows PC still shipped with an optical drive, significantly increasing the height of the PC. Show-goers were openly commenting on the size, weight, and lack of portability of Windows PCs compared to the MacBook Air, which was what many were fully lusting for and based on the numbers had already switched to. For the two years since the MacBook Air launch the PC makers were pre-occupied with netbooks.

Apple broadened their product line with an even smaller and lighter MacBook Air using an 11.6” screen. They also added MacBook Pro models that were more in line with Windows PCs when it came to hardware, for example they included optical drives and discrete graphics. These laptops were expensive relative to mainstream business PCs running Windows. For example, the Dell XPS 15 debuted in 2010 was praised by the press, though only relative to other PCs. Compared to MacBooks, the Dell lost out for a variety of reasons including noise, keyboard feel, trackpad reliability, screen specs, and more. In reviewing the new Dell XPS, AnandTech, a highly regarded tech blog, said:3

We've lamented the state of Windows laptops on numerous occasions; the formula is "tried and true", but that doesn't mean we like it…what we're left with is a matter of finding out who if anyone can make something that truly stands out from the crowd.

Of course, if we're talking about standing out from the crowd, one name almost immediately comes to mind: Apple. Love 'em or hate 'em, Apple has definitely put more time and energy into creating a compelling mobile experience.

If only there had been a Windows PC like MacBook Air for Windows 7. The closest we had was the low-volume and premium priced Sony VAIO Z that was new for 2010. This model featured a solid-state drive like the MacBook Air but was much heavier and larger than the famous envelope and could easily top $3000 when fully specified.

This knocked the wind out of me. I was happy that there were Windows 7 PCs at the show. But seeing the reaction to them only reinforced my feeling that the ecosystem was not well. I was hardly the first Windows executive to bemoan the lack of good hardware from partners, especially hardware that competed with Apple. Six years earlier, before the MacBook Air but also around CES, my predecessor JimAll sent a polemic, intentionally so, to BillG, Losing our way…in which he said, “I would buy a Mac today if I was not working at Microsoft.”4 As with many of these candid emails, this one made its way to an exhibit in a trial—it added nothing to the case, but such salacious mails that have little by way of legal implications are often used to attempt to gain leverage for settlements or stir emotions in a courtroom.

By the time the show ended, I wrote up my CES 2010 trip report as I had been doing since about 1992 or so. I loved (and still love) writing up these reports. No matter how down I was or how boring I thought the show was, I amped up the excitement as though it was the first CES I ever attended. I think it is important to do because otherwise the aging cynicism that seeps in—often seen in the press covering the event—makes it too easy to miss what might be a trend. My report ran 20 pages with photos and covered everything from PCs of all shapes and sizes to 3D television to iPhone accessories (lots of those.)

Not lost on everyone at the show was how Apple loomed over the show even though it had zero official presence. The vast majority of accessories located the edges of the Sands Exhibition Center were cases, docks, cables, and chargers for the iPhone. The camera area was filled with accessories to turn an iPhone into a production camera, such as a Steadicam for an iPhone that I even mocked in my report, oops that was way off base. The real news, however, was that the gossip of a forthcoming Apple tablet was everywhere. Nearly every news story about the show mentioned the one tablet that wasn’t there.

The week before CES in a classically Apple move, invites were sent to the press for an Apple Special Event to be held January 27, 2010. Leading up to the event, rumors swirled around how Apple would introduce a new touch computer and eventually converged on a 10” tablet to be based on iPhone OS. As we see today, the rumors were wildly off base, and only days before did the rumors mostly match the eventual reality.

After the first day of CES and our contribution to the main keynote by SteveB, that evening, I was in a mood and not a good one. I skipped yoga (at the awesome Vegas HOT! studio) and a previously planned celebratory team dinner that I arranged (!) to write a memo. Maybe memo isn’t the right word. It was another dense thought-piece from me, a 6000-word SteveSi special for sure. I think JulieLar, MikeAng, and ABurrows are still angry with me for missing that dinner.

I knew mainstream PCs were selling well. PCs from Dell, Acer, and HP met the sweet spot of the market, even among a marketplace overdosing on netbooks. People were over the moon for Windows 7. Office 2007 was doing quite well, despite not having compatibility mode, which had receded to a non-issue. Windows Server and associated products were going strong even though cloud computing had taken over Silicon Valley. Even Bing was showing signs of life six months or so into its rebranded journey, which had been managed by Satya Nadella (SatyaN) for the past few months. These all made for the bull case that Microsoft was making progress.

For customers and the tech industry, well, their attention had by and large moved to non-PC devices, Apple versus Google in phones, and the potential new tablet form factor. Microsoft launched the HTC HD2 running Windows Mobile 6.5 at CES. It was a well-received and valiant effort while Windows Phone 7 progress continued even in a decidedly iPhone world.

I remained paranoid, Microsoft paranoid. The dearth of premium PCs to compete with Apple and the lackluster success with touch gave me pause. Even though we had tried to right all the wrongs of introducing new hardware capabilities with new approaches, we had failed. There were no Windows 7 touch apps. There never would be. It was totally unclear if the industry would ever come together to create a MacBook Air, and even if it did it was unlikely to have the low cost, battery life, and quality over time of a Mac, even though it too was running on Intel. The browser platform consumed most all developer attention, with iPhone and then Android drawing developers from the browser. Apple’s App Store, 18 months old, had 140,000 apps up from 500 at launch, growing at a rate of 10 to 20 percent per month. To put that in perspective, during the Windows 7 beta I shared what I thought was an astoundingly large number—883,612 unique Windows applications seen across the massive beta test. By mid-2022, the Apple store had more than 3.4 million apps!

A sense of dread and worry came over me when I thought about our converging Windows 8 plans. It wasn’t a panic attack. It was more me wondering if I failed to give clear enough direction to the team about how big a bet we were willing to make on Windows 8. Was I too subtle, which I was definitely known to be, and gave too much room for the plan to turn into an “and” plan? An “and” plan means we would do everything we would have normally done, “and” also take into account all the new scenarios. Such plans are easy to sign up for because they don’t involve tradeoffs. At the same time, they force no decisions and lacked the constraints that yield a breakthrough design.

An “and” plan is what I saw across the CES show floor and even from Intel. It is a plan where the PC is a Windows PC and the new stuff, as though the new stuff is just another app one could take or leave. The extra launcher shells, content stores, and touch interface were bolted on the side of Windows and did not substantially alter the value proposition that was under so much pressure. Related, an “and” plan would also presume a traditional laptop or desktop PC as the primary tool, which itself would prove as limiting down the road as it was right then.

We needed a plan with a point of view about how computing would evolve. That point of view needed to be built upon the assumption that Win32 was not the future, or even the present. We needed to realize that an app and content store were of paramount importance. We needed to account for shifting customer needs in their computing device. We needed a plan that assumed the web is the defining force that changed computing and smartphones were themselves changing the web. We needed a plan that substantially changed the futzing, viruses, malware, and overall fragility of the PC so it acted more like a consumer electronics device. Most of all we needed a plan to engage developers in a new way to become interested Microsoft’s solution this opportunity, and not the solutions from Apple or Google.

We had the ingredients of a plan that might be adequate to quell the forces of disruption. Would executing such a plan be possible within the context of Microsoft? What does a plan look like when it also involves Windows itself?

The Windows 8 framing memo I wrote and the planning memo and process JulieLar had started contained the core of a point of view. We had set out to investigate “alternative hardware platforms,” potentially “distributing applications in a store,” designing “a modern touch experience,” and much more. As interesting and innovative and outside the box as these were, they all suffered the same risk. The problem was that for the team they were viewed as additions to Windows, as add-ons to the next release, as nice to have, an addition to. We had—and this is where the discomfort came from—created a classic strategy of the incumbent when faced with disruption. Our strategy treated the forces of disruption—in this case mobile hardware platforms, modern user interface, and the app ecosystem—as incremental innovations in addition to what we had. We were thinking that we would be competitive if we had Windows and other features.

This is not how disruption works.

Disruption, even as Christensen had outlined a decade earlier, is when the new products are difficult for the incumbent to comprehend and are a combination of inferior, less expensive, less featured, and less capable, but simultaneously viewed by customers as superior replacements.

As a team, we had faced this before, and I had spent the better part of three releases of Office fending off those claiming Office was being disrupted by inferior products built on Java, components, or browsers. In all those instances, I stuck to what I believed to be the case and defended, effectively, the status quo until we took the dual risks of expanding Office to rely on servers and services and then redefining the user experience for the product. Patience paid off then. The new technology threats were immature at best and a distraction at worst.

What gave me the confidence to believe, as they say, this time was different? Was it my relative inexperience in Windows of just one release? Naivety? Arrogance? Was it envy of Apple or Steve Jobs?

It was none of those things.

It was simply the combination of the shortcomings I was seeing on the CES show floor and the fact that we’d all been using iPhones. We were not talking about a theoretical disruption where someday Java Office could have all the features people wanted in Office or that someday all the performance and UI issues would be squeezed out of the browser. The disruption had already happened, but the awareness of that was not shared equally by everyone involved.

To use a phrase attributed to William Gibson, “The future has arrived—it’s just not evenly distributed yet.”5

Windows had 100% share of the Windows PC market and 92% share of the PC market. iPhone and Android (phones, and soon other form factors) were making a compelling case that the Windows position, as a percentage of computing, was declining. This decline in computing share would only accelerate.

In technology, if you are not growing then you are shrinking.

Holed up in my hotel room while the rest of the team had dinner, I banged away at my netbook keyboard a screed about the future of the web, apps, and how consumers would interact with content—and, importantly, ways in which the PC was deficient. I wrote 6,000-plus words, making the case that the iPhone was so good the internet was going to wrap itself around the phone rather than the phone becoming a browser for the existing internet—the web would tailor itself to the phone via apps. The experience of the web was not going to be like it previously had been—the iPhone was not going to deal with the desktop web and attempt to squeeze it on to the phone. The browser itself would become a form of legacy, “the 3270 terminal” of the internet era. The 3270 is the IBM model number for a mainframe terminal, replaced by PCs and applications.

As the office workers I gave first PCs to in 1985 did not realize, the business forms they filled out with their Selectric typewriters would change to work on a PC, not that the PC would get good at filling out carbon paper forms. A key part of a technology paradigm shift is that the shift is so significant that work changes to fit within the new tools and paradigm. There’s only a short time when people clamor for the new technology to feel and behave like the old.

I sent the memo to a few people that night. It received a bit of pushback because it felt like what we were already doing, only restated. I kept thinking this was how disruption really happened—teams went into denial, say “We got this” and believe adding a bit more would make the problem (or me) go away. IBM added a 3270 terminal emulator to the original PC for this reason, but that didn’t make people want a PC more or even use it; rather, they complained that the terminal seemed more difficult to use than a standard 3270 terminal. The PC I most frequently installed in the summer of 1985 was the IBM PC XT/3270, a hybrid mess if there ever was one.

It was clear we were falling into the trap of thinking incrementally when the world around us was not only changing but converging. The Windows team could no longer think of modern mobile platforms as distinct from the PC. People’s technology needs were being met by phones and were moving away from the PC.

This was not a call to turn the Windows PC into a phone. Rather this was a chance to up-level the PC, to embrace the web, embrace the app store model, embrace the shifting hardware platform and associated operating system changes, and embrace internet technologies for application development.

Most of all it was about “apps” except I couldn’t quite find the right word to use. Apple talking about “apps” for the past couple of years really bugged me. When I was in Office, we were the Applications (or Apps) group at Microsoft and an app was just the techie word for another more broadly used techie word, program. Word and Excel were apps and I was trying to define a new kind of app. App was such a weird word that even our own communications team didn’t think we should use it. Lacking a better word that night in the hotel, I called the memo “Stitching the Tailored Web” which was a horrible name and worse metaphor that took a lot of time for me to explain to people in person.

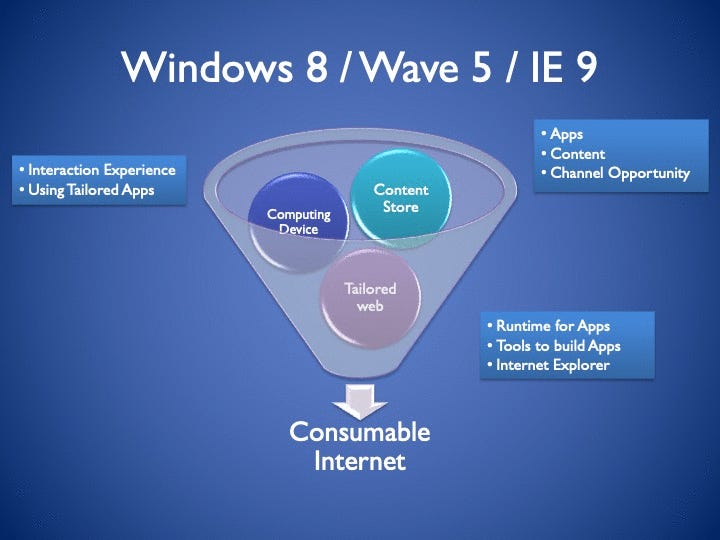

The key ingredients of this new world as I described it were a computing device, content store, and the tailored web itself. The computing device encompassed an interaction model for the device and for the new tailored apps. The content store is where users obtained apps created and distributed by developers along with consumable content such as movies, books, and music. The tailored web included the APIs used by developers and the OS platform, the new tools required by developers, as well as the core technologies of Internet Explorer used to create these applications and to browse the traditional web. All three came together to create what I described as the more “consumable internet.” I even had a fancy diagram I made with PowerPoint to illustrate the point.

My main point was that mobile phones were so huge and such a force that even the internet would change because of phones, the iPhone in particular. The notion of going to web sites would be viewed as quaint or legacy compared to apps. Today, there are plenty of people who do not take this point of view to be where we landed. There are those that use desktop PCs and live in a desktop browser and defiantly believe that to be the only way to get real work done. They use the highest-end PC tools such as Visual Studio, Excel, AutoCAD, and Adobe Premier and did not (and still do not) see phones or mobile software replacing those any time soon. Yet there is no disputing the vastness of mobile. Depending on the source (and country) about three-fourths of all web traffic is mobile-based, and about 90% of time spent on a mobile device is in an app. With this dramatic change in how the web was used, it is fair to say that the web became a component of mobile, not the other way around. The browser-based Web 2.0 juggernaut would be subsumed by the smartphone.

The most dramatic expression of this would not happen for another 2 years. In the summer of 2012, Facebook, the posterchild of Web 2.0, dramatically pivoted from desktop browsing as the primary focus for the Facebook experience to the Facebook mobile app. That legendary pivot is often touted as both remarkable and responsible for the success and reach the company subsequently achieved.

The Tailored Web memo was much better delivered as a passionate call to the team. I waited until just after Apple’s scheduled event and later that same day held a meeting with our senior managers (the 100 or so group managers across all of Windows, each the leader of dev, test, pm for a feature team.) This was my favorite meeting and one I held at least quarterly going back to the late 1990s in Office.

Working with Julie, this became our own version of a pivot. It was not as much a pivot as simply a focusing effort. We still had about three months until the vision needed to be complete. This was by no means a major change. Rather it was relaxing the constraint that Windows 8 had to do two things, an “and” project, and it could focus on making sure we were set up for the future. The call to action was a call to prioritize the new over the legacy and interoperability between the legacy and new was not a priority. We wanted to break away from what was holding us back, a legacy neither of our primary competitors dealt with.

To the team, I wanted to make the case about apps by showing a series of screen shots of web sites versus Apps on various platforms and rhetorically asked “Which would you rather use?” Facebook on iPhone or a desktop? Crowded, ad-filled Bing on a desktop or the Bing search app on Windows Mobile? Outlook or the Mail app on iPhone? Reading a book in a browser or on a Kindle? A traffic map on a desktop browser or in the Microsoft Research SmartFlow traffic app?

The answer was obvious for all of us and remains obvious even today. The call to action was a doubling down on the developing planning themes “Defining a Modern PC Experience” and “Blending the best of the Web and Rich Client” with an emphasis on consumption and the internet. Specifically, it was “Windows, in all form factors, needs to be the best platform and experience to consume internet content while enabling ISVs and IHVs to build the software and hardware to do that.”

It was early in the potential for this disruption, and it was easy to point to thousands of tasks, features, scenarios, partners, business models, ecosystems, and more that required a PC as we knew it. Every situation is different, but it is that sort of defensiveness that prevented companies like Kodak, Blackberry, Blockbuster, and more from transitioning from one era to another.

It is easy to cycle from anxiety to calm in times like this. It was easy for me to look around and find affirmation of the “and” path we were on. Every stakeholder in the PC ecosystem would be far happier with incremental improvements to the status quo rather than embarking on huge changes with little known upside and significant immediate cost and potential downside. It would have been easy to fall back on the financial success we had and leave dealing with a technology shift for the future when technology specifics were clearer. It would, however, be too late as we now know. We would also lose the opportunity to lead a technology change that had just begun.

Worrying seemed abstract. Developing a clear point of view and executing on that seemed far more concrete and actionable.

The announcement from Apple and their tablet turned out to be far more than our poorly placed sources had led us to believe. What was it like in the halls of the Windows team on that day, January 27, 2010? It was not magical for us.

On to 099. The Magical iPad

Nvidia finished fiscal year 2021 with revenue of $26.9B and a net income of $9.75 billion, with a market capitalization of $735.3 billion, with a b. via Nvidia annual report and Q4/21 report.

http://ptech.allthingsd.com/20070405/pcs-mired-in-chores/

“Dell XPS L501x: An Excellent Mainstream Notebook” in AnandTech, November 10, 2010, https://www.anandtech.com/show/3999/dell-xps-15-l501x-review

https://blog.seattlepi.com/microsoft/2007/01/10/jim-allchins-mac-message-the-full-text/

Quote Investigator, https://quoteinvestigator.com/2012/01/24/future-has-arrived/