062. Split Up Microsoft

"In other words, Microsoft enjoys monopoly power in the relevant market." —Findings of Fact, US v Microsoft, November 1999

Writing about the antitrust court case and the final judgement can be difficult. The topic has been covered extensively and by my own count, of the dozen or so books about Microsoft almost all of them are primarily focused on the trial years and Microsoft achieving monopoly status. If you’re interested in the legal details or stories from competitors those sources are all better. These two sections are about the most dramatic years from the time of the initial Findings of Fact to the resolution. In all the years Microsoft was involved in litigation, before and after, this time was the most challenging. The uncertainty was high and the external forces pushing for the most dramatic outcome—splitting Microsoft—were intense. I wanted to write about the way I felt and the impact to the team.

Note: This mailing delivers two sections at once, 062. and 063.

Back to 061. BSoD to Watson: The Reliability Journey

On June 7, 2000, the verdict, known as the Final Judgment, was delivered. I read the PDF (itself a scanned copy of a fax from the legal team) on my Blackberry flying back from a Windows conference. In-flight connectivity didn’t exist, but the Blackberry magically worked over the pager network, downloading a few sentences at a time while I avoided looking like I was using prohibited electronics in the air.1

The Plan shall provide for the completion, within 12 months of the expiration of the stay pending appeal set forth in section 6.a., of the following steps: The separation of the Operating Systems Business from the Applications Business, and the transfer of the assets of one of them (the “Separated Business”) to a separate entity along with (a) all personnel, systems, and other tangible and intangible assets (including Intellectual Property) used to develop, produce, distribute, market, promote, sell, license and support the products and services of the Separated Business, and (b) such other assets as are necessary to operate the Separated Business as an independent and economically viable entity (Final JudgementJune 7, 2000)

Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson ordered the breakup of Microsoft into two companies, though there was a debate over whether it should be two or three companies, after listing all the federal and state laws Microsoft violated. The punditry (and press) all but declared victory. The dragon had been slayed. Magazine covers across mainstream and industry press featured all varieties of busted and gotcha.

The litigation began way back in July 1994 when I was working for BillG as his technical assistant with a lawsuit by the Department of Justice, DOJ. Microsoft and DOJ entered a consent decree to resolve the case, but then in 1998 the DOJ sued Microsoft in civil court for violating the terms of that agreement as it pertained to how Microsoft licensed Windows to PC makers. Microsoft initially lost the case, but on appeal it was ruled that Windows 95 bundling Internet Explorer did not violate the agreement. There was a catch though. The resolution of this case did not preclude further action for violating antitrust law.

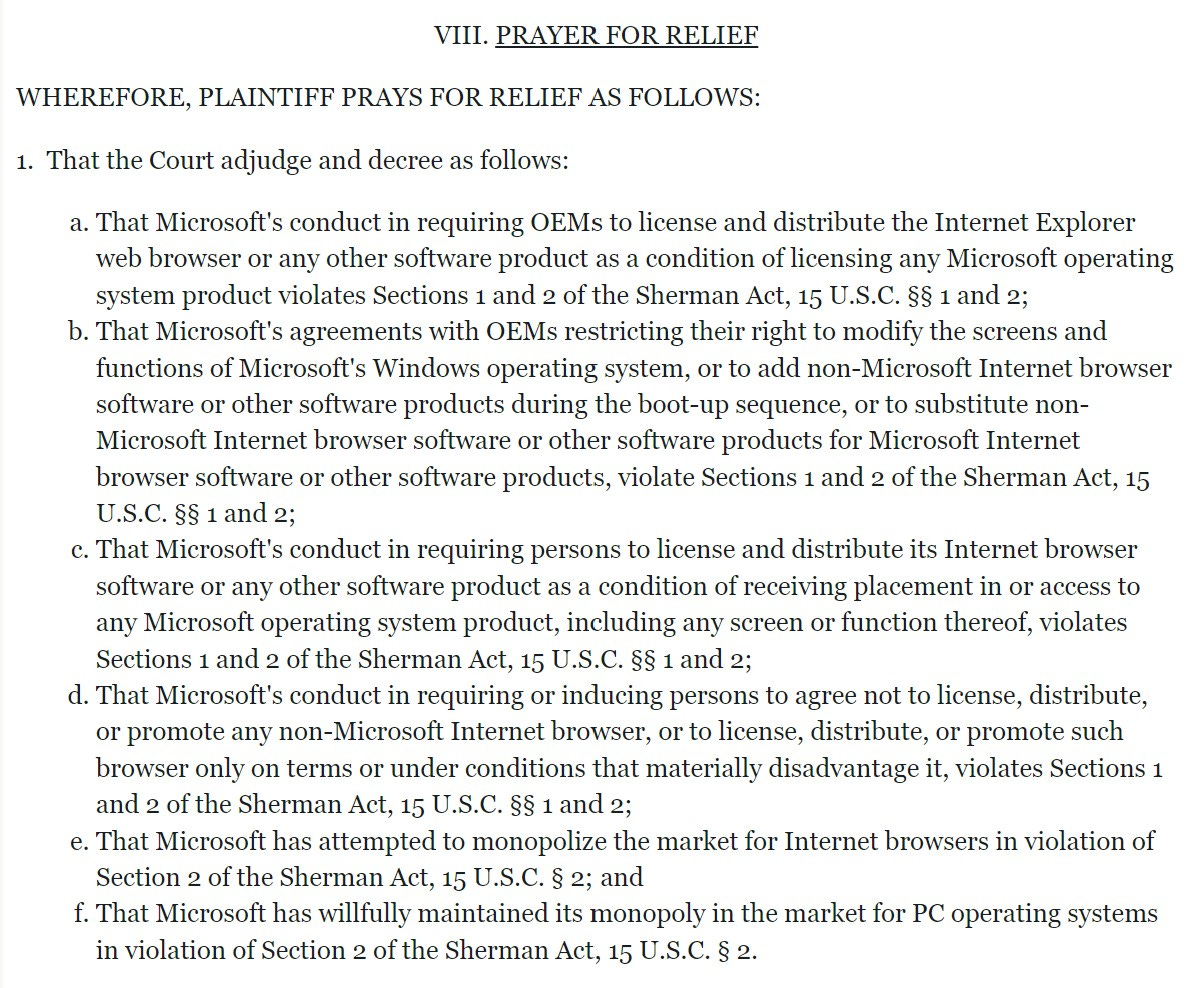

Filed May 18, 1998, the US Justice Department and 20 state attorneys general sued Microsoft for violations of the Sherman Antitrust Act. The suit charged the company with abusing its market power to impede competition, especially Netscape. Running over fifty pages, the initial complaint read like a greatest hits of emails, comments, and things we probably should not have said. All the classics were there from "We are going to cut off their air supply. Everything they're selling, we're going to give away for free” to “You see browser share as job 1 . . . . I do not feel we are going to win on our current path. We are not leveraging Windows from a marketing perspective” to “Integrate with Windows [to] increase IE share”.

The trial and subsequent rulings were low points for Microsoft. While the Office team was not part of the offending acts it was very much part of remedy being tossed about. From BillG’s deposition performance to the botched courtroom exhibits to the lack of voices of support from so many that benefitted from Windows, there were plenty of moments to feel awful about. The industry tracked the trial, but the pace of coverage was nothing like we see today with instant commentary and analysis at the speed of Twitter. By and large most employees did not follow the trial day to day and even the daily summaries that went out to some execs were not the most important thing. Even with all these negatives, the team of people at the trial were working incredibly difficult and long hours with a strong sense of purpose and pride. At an exec staff meeting, a Windows executive returning from the trial said to me they genuinely believed it was Microsoft’s “best people doing some of their best work”. There was optimism throughout the trial, until we lost.

Some aspects of the case stuck with me more than others. One in particular was the finding about bundling Internet Explorer with Windows. The judge wrote in the Conclusions of Law, April 3, 2000, that “Microsoft's decision to tie Internet Explorer to Windows cannot truly be explained as an attempt to benefit consumers and improve the efficiency of the software market generally, but rather as part of a larger campaign to quash innovation that threatened its monopoly position.”

I felt that being explicitly called out for building products to “quash innovation” was particularly brutal. With the passage of time, I have come to recognize that if you have faith in the system that governs us, it is fine to disagree with a particular ruling, but one must accept it as a fact because the system does. Even if I disagree, most everyone else will go by what the court held to be the facts determined through the process. I held (and continued to hold) a product person’s view of product development, which is that the work of product development is somehow a higher calling and done for the benefit of customers, partners, and the market. It is fair to say this is a horribly naïve view that doesn’t consider the realities of running a business in a brutally competitive market. This belief of mine would be put to the test later in my career when I found myself managing Windows.

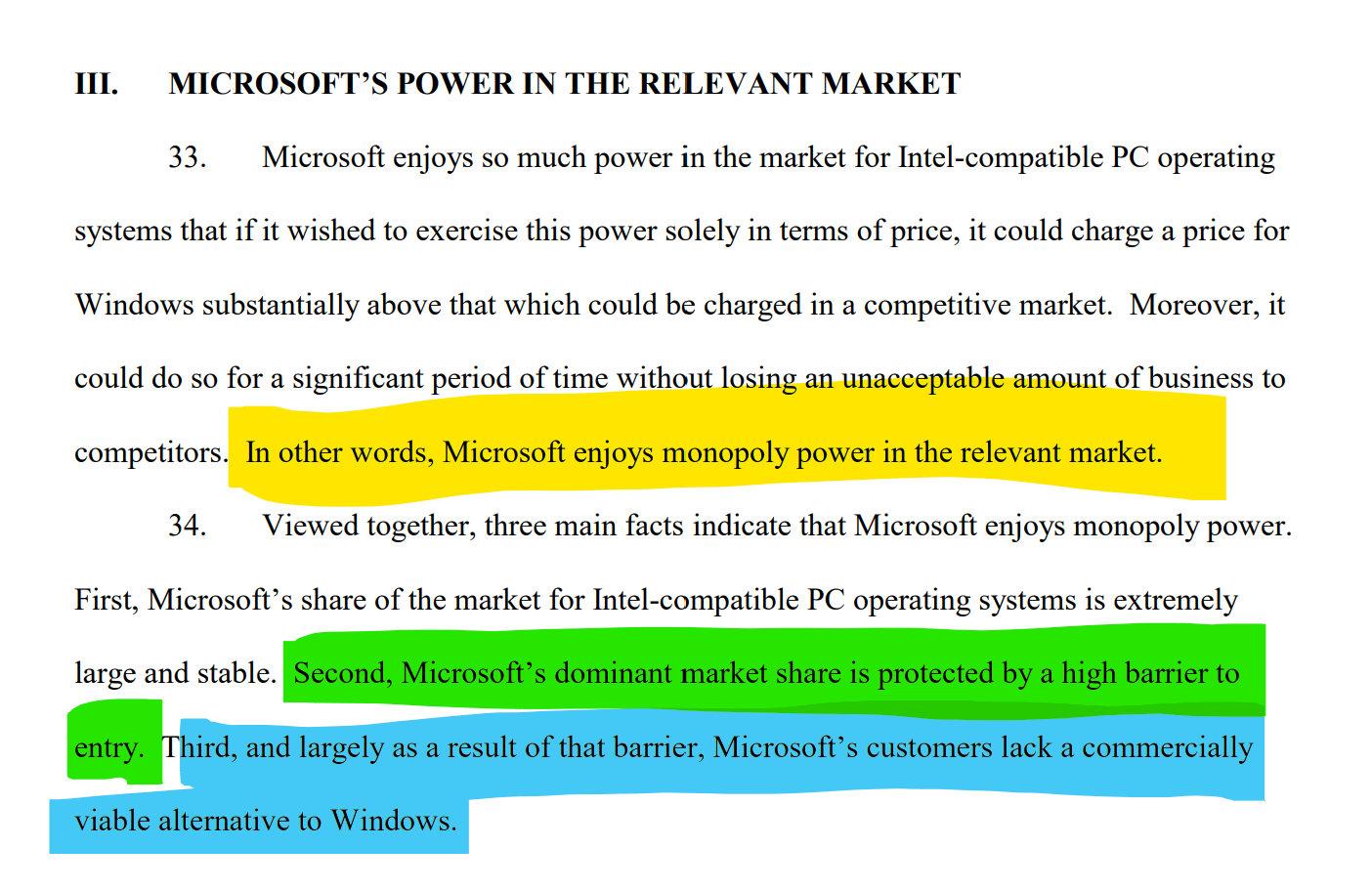

In the Findings of Fact in November 1999, the judge found that the company held a monopoly—an important finding that forever changed how Microsoft was viewed. Following that was a lot of back and forth about the penalties, but once the company is labeled a monopoly, something was going to happen.

Viewed together, three main facts indicate that Microsoft enjoys monopoly power. First, Microsoft's share of the market for Intel-compatible PC operating systems is extremely large and stable. Second, Microsoft's dominant market share is protected by a high barrier to entry. Third, and largely as a result of that barrier, Microsoft's customers lack a commercially viable alternative. (US v Microsoft,Findings of FactNovember 5, 1999)

It was in that Final Judgment in June 2000 that the judge ordered a structural remedy and the splitting of Microsoft into two companies. One company was to be the Windows company, and the other was to be made up of the rest of Microsoft including Office. The case had finally hit close to home.

Looking back this was a very long road. The investigation started more than six years earlier, after the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) dropped its case in a deadlocked vote and passed the authority to DOJ. I remember the early meetings from when I was working for BillG and how “crazy” all this felt at the time. While perhaps at the highest level the complaints did not change, the details and reasoning changed as the company saw more success. There was a subsequent case focused on violating the original settlement that lasted well into 1998. There was even a moment of daylight in that case when an appeals court ruled in May of that year that Microsoft could indeed integrate any software it would like into Windows so long as consumers benefitted. Then came this massive antitrust lawsuit on the heels of that small victory, often referred to internally as “the big day”.

It was amazing to think how much the industry changed over this time—Windows 95 and the internet came to be—and many said the industry shifts were just starting, yet the case was still there. The arguments put forth by Microsoft insisting that market forces were already at work to “disrupt” Microsoft fell on deaf ears and were viewed as self-serving. The consensus was that Microsoft had reached an invincible, all-powerful stature that needed to be corrected.

As a practical matter, once a trial started little would change for Microsoft unless, well, we lost. Losing took a much longer time (for both sides). Plus, there was always an appeal. Litigation at this level is a slog and a true test of patience. In high school we once had a guest speaker in social studies class who had a role in the AT&T breakup lawsuit which had just concluded with the breakup of AT&T. He told us he had worked his entire legal career on that case. We were dumbfounded. I now know plenty of lawyers who worked nearly their entire professional career on the Microsoft case.

That day in June, it obviously felt like we lost . . . badly.

Microsoft had always been comfortable in the context of litigation, perhaps owing to BillG’s upbringing as the son of a prominent Seattle attorney. The earliest days of the company were characterized by a lawyerly Open Letter to Hobbyists, penned by BillG in 1976. In the letter, he argued that software should be a royalty-based product like music. The letter was controversial in a world where all the money was in hardware with freely bundled and shared software but ushered in the pure-play software company we now know. In all fairness to Bill, the hardware side of the industry was characterized by secrecy, patents, and its own litigation.

The early software industry wrestled with how law applied to this new type of product, a product required for hardware, dreamed up like art, and manifested in a proprietary digital encoding.

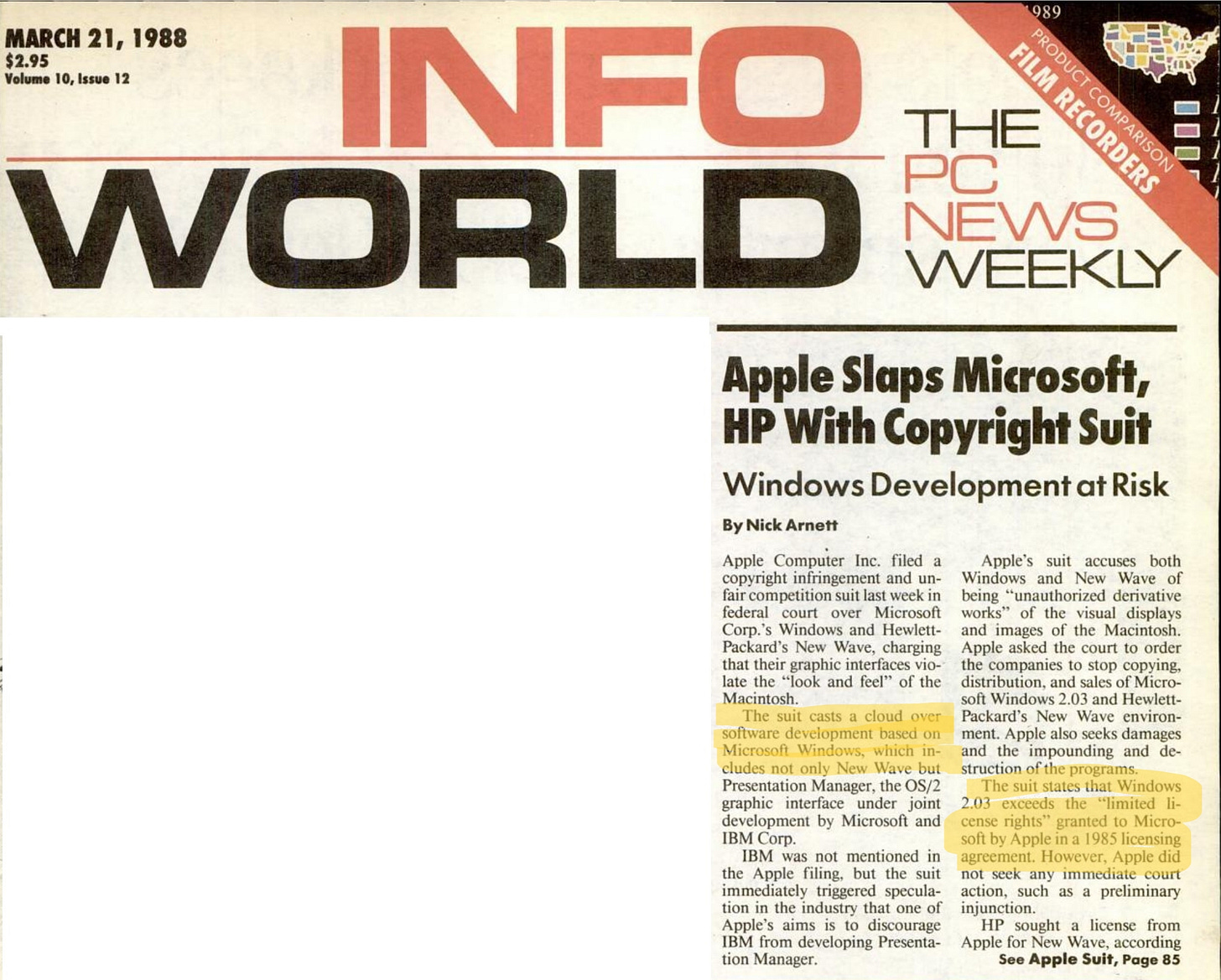

In 1988 (a decade before the antitrust suit), Microsoft found itself in what it would describe as a straightforward contract dispute, and what Apple would characterize more broadly as an intellectual property dispute in Apple versus Microsoft.2 Apple agreed to license elements of the Macintosh software for use in Windows 1.0, partially in exchange for an effort to secure Microsoft applications for Macintosh (Excel in particular). The case was front and center of the industry as Apple claimed a right to the “look and feel” of the Macintosh, which seemed to many rather unbounded, though obviously their product was unique on many levels. In a key ruling for all of software the court stated that, "Apple cannot get patent-like protection for the idea of a graphical user interface, or the idea of a desktop metaphor." While ultimately resolved in Microsoft’s favor in 1996, based on contractual terms, the litigation served to condition employees to the hurry up and wait, and the ups and downs, of the winding nature of the US legal system. For years at the annual company meeting someone inevitably submitted a question for BillG about the case and every year he would say there is nothing new but that we felt good on the merits. In between those times, the various motions and courtroom events were rather baffling to non-lawyers, somewhat like trying to watch a cricket match for the first time and not being sure if something good was happening or for which team.

Litigation was a significant part of the industry in the early days of software as the rules of the road were established for software patents, copyright, and contracts. Another closely watched case was Lotus Corporation, a giant, suing Borland International, an upstart, for copyright violation in 1990. Borland had essentially cloned the interface of Lotus 1-2-3 and expanded upon it in its Quattro Pro product, to smooth the transition from 1-2-3 to Quattro by providing a compatibility mode. This case had profound impact on the ability for upstarts to enter an existing market because whether it was user-interface or API, providing compatibility by reverse-engineering (without having access to source code or trade secrets) was key to expanding the industry. This case was decided in Borland’s favor, allowing for the copyright of the Lotus implementation but not the expression of user interface in Borland’s product.3

These as with other legal matters were often discussed more as curiosities than existential risks to the company, at least among us less senior people that had no inside scoop on the matters. Even when working with BillG, a time when many of these issues were front and center for the company, he did a remarkable job of compartmentalizing the challenges. Importantly, except for the yearly question at the all-company meeting, these topics were hardly discussed within product groups or large forums and we were always cautioned to do what we believed was in the best interests of the product and not to try to think like lawyers (a cultural challenge I would face when I moved to the post-antitrust Windows team years later).

As these suits were winding their way through the system, Microsoft’s rise to the largest software company and its new power position as an unabated leader continued. From the outside, Microsoft had all the appearances of a growing software empire. From the inside, Microsoft was paranoid and felt everything was fragile and could evaporate at any moment—just as we had seen happen to the fortunes of nearly every technology company before us.

I can’t emphasize this point enough. Microsoft saw all the previous microcomputer companies, many application companies, stand-alone word-processing companies, and of course the mainframe and mini companies all but vanish in the blink of an eye, falling victim to a new generation of technology. I mean Marc Andreessen himself had predicted that Netscape would render Windows a “poorly debugged set of device drivers” (he later attributed the statement to Bob Metcalf) and Microsoft’s nemesis Scott McNealy at Sun Microsystems never missed an opportunity to ridicule the quality and utility of Office. Disappearing was one thing, but from a business strategy perspective, Microsoft was deeply concerned about having our competitive advantage removed by non-market forces. We’d seen what happens when a company like IBM or Intel are made to surrender their earned advantage (or in business school terms, their moat). Somewhere between fragile upstart and unstoppable force was the truth. It would take more than a decade from the first regulatory inquiries until resolution reaching some sort of détente with regulators around the world.

In hindsight, it shouldn’t have been a surprise that a company could become the most well-capitalized company in the world and as a result be subject to regulation. Microsoft’s views that we were just selling software at very low prices that customers and partners put to good use seemed rather quaint and naïve. The government was struggling to wrap itself around how such a huge success could come to exist without any involvement of regulators. The rise of the internet, originally funded by government research, only served as a reminder that something huge was shaping our economy and was essentially free of any government oversight. Normal issues that governments oversee such as product quality and safety, sales and marketing practices, even employment procedures had all gone unchecked. That a company maintained unfettered influence over massive societal changes was basically unacceptable.

It was always difficult to separate out the problem needing to be solved. Was it the problem of what Microsoft did? How Microsoft did that? Or was it simply the scale of success Microsoft achieved?

This mismatch of perspectives—Microsoft as a paranoid upstart just trying to keep up with the popularity of its products and a government blindsided by unregulated corporate growth and power—created a difficult situation, which required the legal and regulatory systems to resolve. Analysts, pundits, former regulators, and competitors can propose “remedies” (as if the success of Microsoft was an affliction) faster than the system can understand the problem (few in government had any expertise in software) and address it in the context of the existing laws.

Competitors complained about one set of problems. Consumers complained about another. Partners had their own issues. Economists and academics had views too. The law had its own definitions of problems. Two things were notable about this early time in Microsoft’s massive success and “power”.

First, parties were seeking a remedy for this problem that was not yet defined as we often liked to say. We lacked specifics, even with the 50-page complaint. Was it simply the scale of Microsoft? Was it that Windows had come to dominate the operating system market for PCs? Was Windows a monopoly? Were PCs to be treated like common utilities? Was Microsoft’s business model of low-price, high-volume problematic? Was it unacceptable for one company to sell operating systems and to sell applications? Or was this about some other type of product integration such as browsers and media players? These questions did not have obvious or consistent answers back then, even among third parties. The complaint said Microsoft could not integrate a browser into Windows, but few complained when Windows added networking, file management, or game graphics. There were examples of common business practices to counter every complaint.

Second, assuming agreement was reached on the problems being solved, what would the right regulatory framework be? How do you solve the problems identified? The experts in regulation (and antitrust) were themselves products of the incredibly long-running cases of IBM, AT&T, and others. In the technology industry we looked at the IBM case and saw litigation solving the problem long after it mattered—the whole industry moved on to mini-computers, workstations, and then PCs from mainframes and it seemed this case was still going on, a condition that created a view that regulating the fast-moving technology industry did not make sense the way it might for the industrial economy. The AT&T case seemed remote as it was created by the government as a monopoly and primarily involved physical cables, and much of the unleashing of competition that took place came about not because of the new regulatory framework as much as what AT&T fought for (for example, they quickly sold off the cellphone operation for a small amount to focus their win on long distance lines). But the breakup of AT&T was on everyone’s mind and that led to calls to breakup Microsoft—it seemed clear if there’s a monopoly it needs to be broken up into pieces. The debate over whether regulation simply stifled one of the most inventive and successful companies in US history continued.

This set up for a confrontation as the process wound through, with each side articulating extremes, and neither side particularly good at stating problems or matching problems and remedies. Microsoft, especially from its paranoid mindset as an upstart, insisted that it had done nothing wrong but make products people bought and so any interference was paramount to killing off innovation just as had happened to IBM. The punditry would opine about the need for choice and alternatives in products and suggest that Microsoft was itself already stifling innovation.

All of this activity changed the company’s narrative. A few years earlier, BillG was a boy wonder, the under 30 founder who had grown a new industry for the world through the magic of software. By the mid-1990s, Bill and the company were ruthless competitors who rolled over every other entity, dictated terms for the industry, and above all could enter any market and dominate. It was this fear of what Microsoft might choose to do next that drove the most extreme views of regulatory remedies—the government needed to do something to prevent Microsoft from becoming a real-world RAMJAC, from Kurt Vonnegut novels.

Regulatory norms over a new industry were unavoidable. Governments are empowered to provide oversight and there was simply no way the newest and seemingly largest and most important industry would escape regulation. It did not matter how we thought of the fragility of our industry or even how much evidence the IBM case offered as to the futility of regulating technology.

We generally learned what little we knew about antitrust in school as it seemed to originate, in industries where a physical lock on a limited supply existed. Microsoft was a company that created an industry with none of those physical barriers, pioneering a licensing and business approach never used before (open licensing versus closed integration), even among the first to charge for software. There were many times we thought it odd that laws written for an entirely different set of circumstances would simply apply. To legal scholars and regulators, such a view was naïve and self-serving. Of course, laws could apply the lawyers would tell me.

We wished someone could have made a good argument as to why technology was different than say banks, telephones, farms, oil, autos, theaters, or shoes. But technology was not different. We quickly learned that trying to tell the regulators or those immersed in the legal system that technology was different was poorly received at best, and destructive to the dialog at worst. Simply being new was not a free pass through the system, not matter how techno-optimistic we might have been. Rather, we were naïve.

On the other hand, it would have been equally fair to have asked for those calling for remedies to do a better job articulating the problem being solved. And therein lies the challenge. Jumping to remedies that so clearly did not address the problem only made one question motives and create the appearance that parties were further apart. Championing remedies that seem to be designed to simply kneecap a single company don’t serve an industry, or an economy. The political (versus legal) nature of proposed remedies only gets worse when we experienced the grandstanding in the halls of the Capitol or in endless quotes and op-eds in national publications.

Given the inevitable, but also the wide gap between parties, the process took a long time. It wasn’t debilitating as some might have suggested. There was learning, discovery, and socialization. The process was more like having a chronic condition with relapsing-remitting pathology. Long periods of time went by without symptoms, then suddenly and unexpectedly there was a flare up, like the opening of new complaint by a regulator, a country getting involved for the first time, a legal filing, or even a dramatic courtroom moment. We were in an ongoing state of “hurry up and wait” as Bill Neukom (BillN), Microsoft’s chief legal strategist during this time would tell me. The process often felt like those NASA drills where you knew at any moment the lights would turn red, steam would fly out of pipes, and a siren would sound signifying a crisis, but you just never knew when that would happen.

Even after all that, the conclusion of the case felt anti-climactic.

With these kinds of cases, the results are rarely as dramatic as early predictions and tend to be far more specific and, well, rational solutions to identified problems. Regulation does work when it is eventually created through the system. It might not be ideal for a newly formed company or for one hoping for more extreme remedies, but it ends up designed to solve the problems that regulators can solve. The problems Microsoft ultimately showed to have pertained to how business was conducted, in a sense these were understood to be problems of monopoly maintenance. Being declared a monopoly was certainly not fun, but in many ways, it was reality—Windows had, in fact, won. It was time for Microsoft to admit that.

Time would show that Microsoft’s argument that technology winning in one era will have a hard time winning in the next was decidedly true. Continuing to debate the end-state wasn’t only futile, but not done. Once a company loses in these cases, it becomes necessary to make way for the winners to own the new narrative. This might be the most difficult part to live through in the near term, and over the long term these same patterns will again play out because to the victors go the spoils, or the narrative.

On to 063. Managing the Antitrust Verdict

For all the details of the litigation, the DOJ web site has a catalog of all the public filings and evidence used in the trial. Specific documents of interest include the Complaint, Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, Final Judgement, and the Consent Decree along with ongoing status reports.

Apple Computer, Inc. v. Microsoft Corp., 35 F.3d 1435 (9th Cir.1994)

Lotus Development Corporation v Borland International, Inc 516 U.S. 233 (1996)

There are two stories from this time I would like to tell. The first is about the political dimension of the anti-trust trial. A prominent politician of the day, Orrin Hatch, said on the record that if Microsoft would have been giving its political contributions that it would have been protected and not had any anti-trust issues. He of course used veiled language, but the message was clear. This started a journey for me participating in the Microsoft Political Action Committee (PAC) and gaining a front row seat to the accelerating money corruption of the US political system. I've dedicated myself to political reform since I left Microsoft.

As part of my political reform work, I have come to know Lawrence Lessig, who was the "special master" assigned to help the court with the anti-trust trial. No matter what one thought of the findings of fact regarding the Windows monopoly and Microsoft's abuse of it, clearly the remedy of breaking up the company made no sense at all. Literally it would have left the teams that created all of the accused behavior intact. (Internet Explorer was part of the Systems Division.) I had an interesting conversation with Lessig about this. He said the thought was not so much to prevent IE from remaining a problem, but the hope that Office being separate would unchain it from "having" to rely on Windows and allow for a Linux version. It was an interesting inversion of incentives and to this day the breakup remedy makes absolutely no sense to me.

I was trying to raise money for a startup focused on mobile in this time period. I loved (love) productivity software so every investor meeting started with “how are you going to compete against Microsoft?” (They mostly ended that way, too, actually.)

I was scared to death of the decree to break up Microsoft. I figured it was more dangerous to have two Microsoft’s than one, but most everyone in the mobile space didn’t see it that way.

It is amazing to me how much the tech and software space changed in just the next few years after that. SaaS became dominant, iOS and Android became bigger than Windows, and Google became the bigger threat to most Internet businesses, even though they didn’t know it yet.