223. On the Toll of Being a Disruptor

It is very easy to be disruptive, but being a disruptor is enormously difficult technically and emotionally

It is tempting to want to see the positives of technology disruption as distinct from the disruptive nature of the person or organization causing disruption. As we all know it is pretty easy to be disruptive in meetings, the workplace, or online without being a force for a disruptive innovation. That causes us to wonder if it is possible to lead such change without being disruptive. In practice being disruptive is probably a necessary part of bringing a disruptive change to the world. It is not pleasant for either the incumbent or the protagonist, but it might be a necessary part of getting something done.

The concept of “disruptive” technologies or more broadly disruption in business goes back to the 1940s and economist Joseph Schumpeter and his concept called “creative destruction”. Creative destruction in the simplest terms is “the deliberate dismantling of established processes in order to make way for improved methods of production”. It can be applied to a broad set of circumstances across technology, government, finance, media, and more. As an economist he was keenly aware of the effects of such destruction, both the intended and unintended, or byproducts of such a seemingly violent way to innovate.

In the mid to late 1990s, Clay Christensen and Joseph Bower coined the term “disruptive innovation” the timing of which coincided with the rise of the modern internet and the broad-based information age. It was in part due to that timing and the businesses successes that followed that the literal meaning became second to the broad and appealing metaphor of being disruptive innovators.

Clay’s (with Bower) Harvard Business Review paper “Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave” and later his book “Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail” became beacons of technologists everywhere. Everyone claimed to be disrupting something. No matter what you were doing you were in the business of disrupting some old way of doing things with your new software and internet way of getting things done. From 1998-2000 (March 10th specifically) delivering groceries, selling pet food, and even creating internet money were all major disruptive efforts—and colossal failures.

We make fun of those failures today. Yet those efforts and many more proved to be not only successful years (or decades) later but wildly successful. What we forget is how much we mocked the people creating these efforts and many like them. What we forget is the litany of experts who predicted their failure. What we forget is just how difficult it was to change things.

One example from that era I will never forget is listening to the CEO and founder of one of the major shipping companies in the world explain in painstaking detail how “local delivery” (that’s what it was called when stuff gets delivered to your house) could never be any faster than the overnight shipment that was then standard, extremely expensive, and used only for very important documents or emergency machine parts and the like. The modeling put forward was detailed and excruciating. It explained why there was no way to ever deliver food or groceries from the source to a home. As a bonus he went on to explain how shipping had a baseline cost that precluded making it free and that returns of goods would always be an exception, which is why there were limits to how much one would end up buying via new-fangled internet shopping.

When a successful founder and executive dismantles an idea so many people are chasing it lends credence that is carried forth through the media, other businesses, and more broadly. The experts spoke. It wasn’t just that they spoke, it was that those attempting to challenge the experts were ignorant at best or at worst simply defying basic laws of physics. The arguments against shipping weren’t about strategy or anything, but physics of miles, time, and gallons of fuel.

Then when companies failed—delivering anything from clothes to cookies—the told-you-so comments were everywhere. Those risk-taking founders were held up as examples of people that didn’t listen to experts. They didn’t “understand” the “real world”. They were naive and wasteful.

Of course, when any sort of creative effort succeeds those same people are innovators. They “defied” experts. They are the “rule breakers”. Then they are celebrated. They creatively destroyed something.

We collectively spend significant time and energy on the “victims” of creative destruction. The companies that failed to innovate and went under. The efforts those companies failed to make or technologies/processes they failed to incorporate or capitalize on. The people that poured their labor and personal capital into efforts that failed. Often these stories turn into blame ascribed to the new success or even the single individual.

In other words, what Schumpeter describes as an essential part of systems results in the demonization of those who try and even those who succeed. Even when someone is celebrated for success, it almost never takes long before they are torn down. As much as people generally love success there’s also a view that however the success is achieved, they must not have been playing fair.

Of course, and I can’t say this strongly enough, there’s nothing in being successful that itself grants immunity from vast transgressions as history has shown. There’s nothing about having entrepreneurial spirit that makes one virtuous.

But, and I also can’t state this strongly enough as well, there is a great deal required to creatively destroy something or to develop disruptive technologies. There’s a very strong requirement that one be able to absorb significant negativity, ignore a vast inbound criticism, and make decisions that indeed have unintended consequences.

There’s one other set of skills required that many find distasteful but are equally necessary. That is, one also needs to be strongly critical of the world—the product, the technology, institution, or process—that one wishes to displace and disrupt. Many find this unpleasant.

Examples of such inter-personal challenges are endless. Some are so classic and the success so great and often so long ago we forget the dynamic. It is worth an example of two to illustrate this and explain why this is all necessary.

When Steve Jobs was leading the introduction of the iPod (this is an iPod example not even an iPhone one) he famously made the initial launch all about the benefits of mobility and having your entire music collection in your pocket. We remember those benefits. At the same time, everything about the product was attacked and often from both sides. From the sound quality to the user interface to the selection of music in the store (2003) were criticized. The music industry which had done the $1/track deal came under fire from the musicians. Because it was the early 2000s and PDAs were popular tech reviewers balked at having a music-only device. Many insisted that mobile phones needed to be the music player. The list goes on and on.

Because Steve, as we all know, was a disruptor at heart going as far back as one can, he had already lived the PC revolution, the failure of Lisa, the rise of Macintosh, the return to Apple, and more. He was not only dismissive of these and other complaints, but he was outwardly aggressive about them. At D2 May 2004, asked about coming out with a phone in this context after the galactic success of the iPod, Steve famously said there was no way to innovate in phones because the “problem with a phone is that we’re not very good going through orifices to get to the end users.”

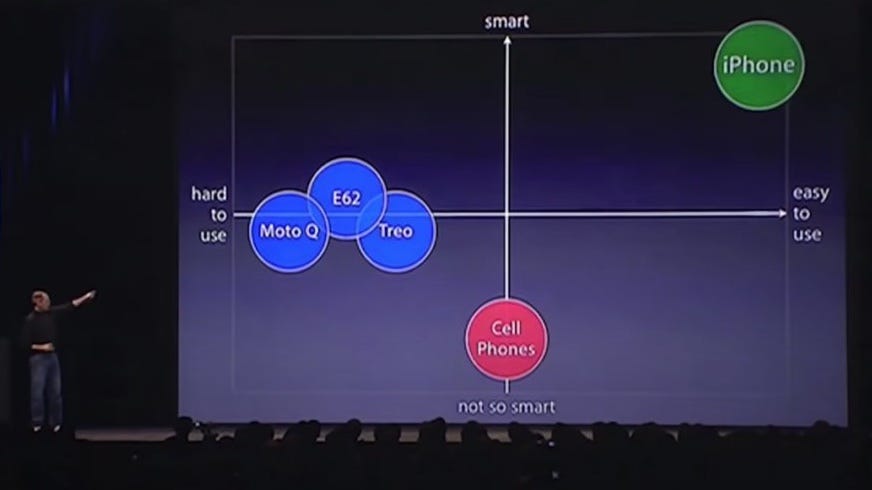

I was in the audience at that moment and can definitely say there was an audible gasp. Here we were at what we thought was the height of cellular/mobile phones with Nokia and Blackberry on top of the world and AT&T/Cingular on a hugest of huge rolls (not unlike today’s semiconductor rally on Wall Street) and Steve just trash talked the lot of them, and rudely so. The reaction of those companies was to be rude back. Industry experts jumped on CNBC and the WSJ with stock charts of Nokia, AT&T, Blackberry, and talked about PDAs more.

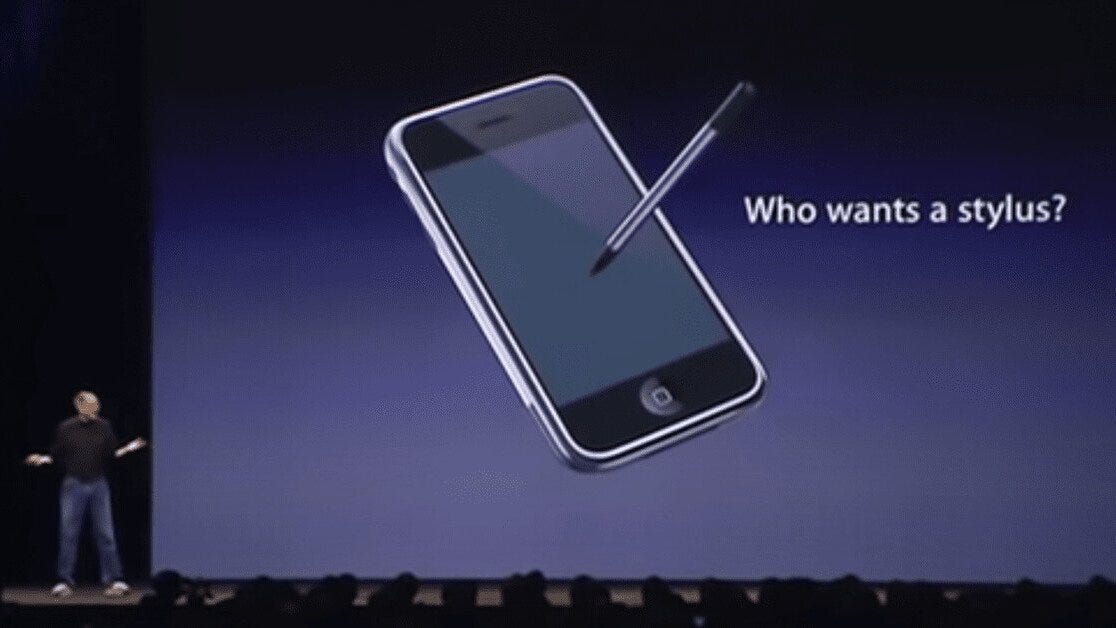

Fast forward to the iPhone launch—a lesson in his reality distortion field and knowing that when Steve trash-talked something he was about to trounce it—and again the entire first part of the launch is a literal takedown of the existing phone industry. He ranted about screen size, little keys, the stylus, weird software, and more. It was brutal.

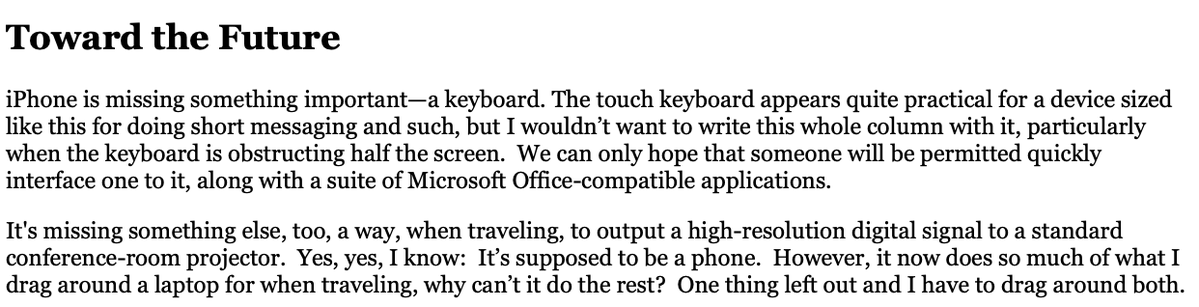

The reaction to the launch was entirely predictable. I watched that reaction from the Windows Phone team (this is the old Windows Phone with the start menu and most models had a stylus and resistive touch screen). The iPhone was dismantled on technical and business grounds. It was too expensive. Touch won’t work. One carrier isn’t how the industry worked. The carriers not ATT/Cingular pointed out that there was no way for the unique carrier services that provided real value to do their job. Blackberry went all in on battery life, typing speed, and their BBM messaging service loved by folks in finance and legal. Apple and Steve retreated from those battles and did the work of execution they knew disruption required.

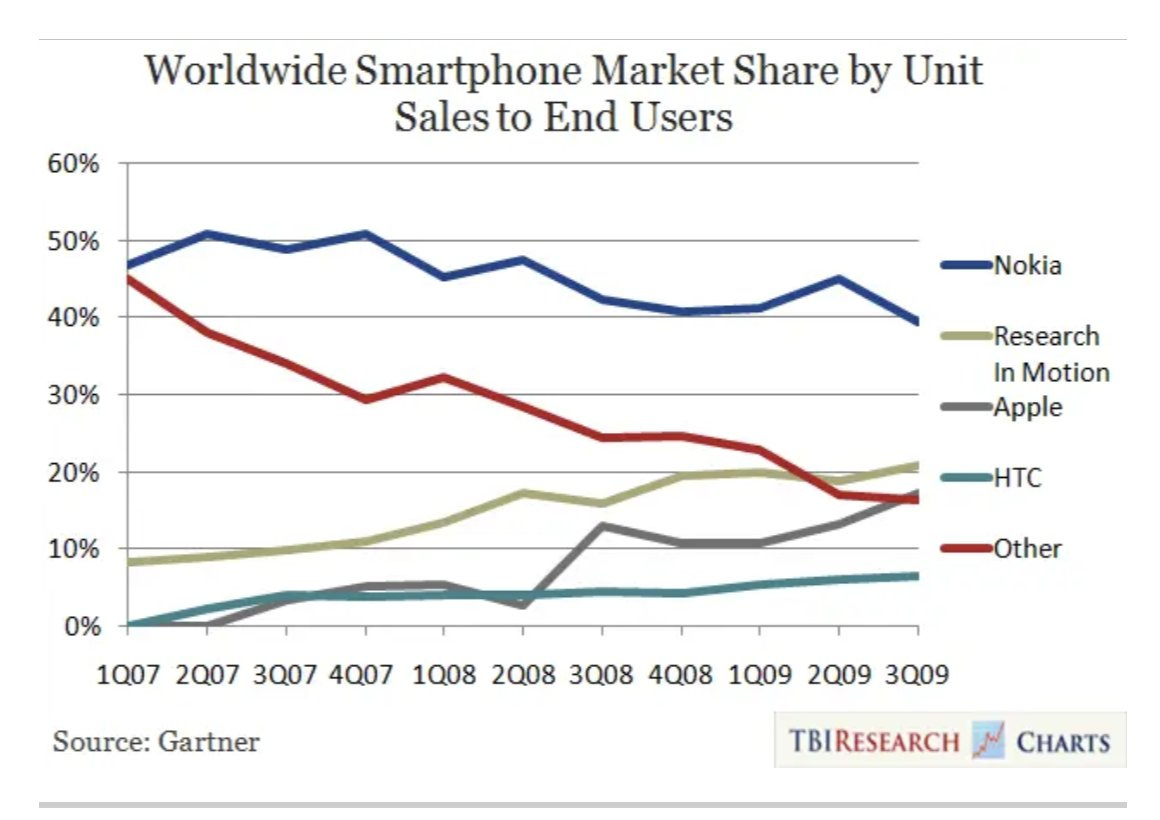

The first year was brutal. It looked a lot like the 1984 Mac. It was an incredibly innovative product that came with the expert consensus that it would be at best a niche. Then the first year of sale were not mind-blowing and the “market share” of Nokia and Blackberry—and importantly their stock prices—did just fine.

Then came apps. Then came failed products that tried to thread a needle in responding. And so on. The rest is history. The creative destruction happened. RIM is what it is today. Windows Phone and Nokia was what they were. The people, teams, and ecosystems moved on. Without that destruction there can be no global smartphone revolution. The displacement of technologies, companies, and even individuals just had to happen. And those steps they took from the 1990s to 2008 or so also had to be taken. Without those innovations, those disruptions, there could have been no baseline to build today’s smartphone. Most reading this are too old to remember, but before mobile phones there were only land lines. Business communication meant an ATT calling card near the gate at the airport or spending an hour making dial up work after hijacking a hotel fax machine phone line. All that infrastructure, all those companies, all those processes were displaced.

So often when this story is told, we look back with nostalgia. We remember fondly the old way of doing things. We remember the glory of the introduction of the new way. We collectively often memory hole the absolute hell that everyone on all sides of a disruption go through. We forget:

Experts telling us all the new thing can’t possibly work.

Incumbents explaining all the problems with the new thing and the societal costs.

Industry leaders detailing the failings of the new approach.

Individuals working on the current products worried and defensive turning into anything from defiance to flight.

Ecosystems around the current product joining in this chorus while defending their own processes, contributions, and businesses.

Everything from public company investor relations to labor unions to trade associations going after the disruptor both the entity and the personalities associated with the disruption.

All of this is done at brutally personal levels. Some might think this is a product of the new online social network world, but above I tried to provide a glimpse of the negatives that flew around. The real costs. The real “attacks” for lack of a better word. There’s nothing that social networks, including X, do that wasn’t already happening. Yes, everyone can see it faster and sure people who aren’t in the nexus of the situation can see it happening and offer their opinions. But no one working on this suffers more because they are already suffering.

The responses or even the first volleys are also brutal and direct, as Steve Jobs was by seeding the fight with carriers. Why is that? This is what it means to lead and be at the tip of the spear of disruption. It isn’t enough to just introduce something even if one gets that far. One needs to build a team that shares the same vision and same spirit of breaking from the past to do something new. In Steve’s case and in most all cases, you must get a whole “system” to change.

Many might think this isn’t necessary or shouldn’t be. But there is no other way. An agent of change is a lightening rad because the default action for every technology, process, business, or institution is to *not* change. The response to potential change is by default to resist change and to protect status quo and incumbency. Change is difficult and individually and institutionally perceived (and in some reality) costly. This is the root of everything from NIMBY to industry groups protecting the industry.

Many also suggest that no matter what a change might be or how significant, there should be a way to ease into a change. Go slow, they say. Compromise they say. This is perhaps at the root of the most polarizing debates. Everyone always wants a simpler and longer path to a change. Why change the user interface all the way, just fix some problems. Why not provide an option to do things the old way. Give us a period of migration and adjustment.

This really doesn’t work the way people think it should. The problem with half-measures is that they are, well, half measures. Taking baby steps all but guarantees the innovation will fail. Amazon famously ignored the experts around retail and refused to accept telephone orders (I had a friend from college who worked hourly staffing a phone center for people calling up trying to order books). The problem is obvious in hindsight which is building out a whole system and process to handle phone orders, phone returns, phone credit card charges, etc. All of those take time and effort away from building out e-commerce which was the goal. Importantly once they would take orders by phone there would almost never be a way to turn it off other than to wait until no people order that way. Think about how long it took Netflix to stop mailing out DVDs or how many people still have dialup internet surprisingly. The long tail not only costs a lot of money and time, but literally prevents disruptive innovations from being fully formed and focused.

Disruption is one of my recurring themes in “Hardcore Software” where I write about accounts going back to just literally using C++ to write Windows programs (“can’t work”) through building a suite of products (“need best of each category”) to introducing a server for Office (“no one wants a server for Office”) to Clippy (embarrassing) to resigning Office head to toe, and yes Windows 8.

One of my most significant and early lessons that helped me to see the personal cost to experts when it comes to what I think everyone might consider routine innovation is when we did the most mundane thing to the “setup program” for Office in the 1997. This was literally just the way files got copied from the floppies to the hard drive to run. Enterprises customized Office setup back then and to do that they would edit what amounted to our *internal* table of files to be copied, SETUP.INF. It was a crazy format fragile and inscrutable, but necessity mandated they figure it out.

We introduced a whole fancy new database (you might know this as MSI files in Windows today) to make it “easy”. In the process, though, the very people we were trying to help ended up hating, I mean hating, what we did. Why? Not because it wasn’t better. No, simply because it was totally different. We were victims of our success and by changing it we took away their skills. We make it harder for them to be successful. They didn’t pay to price of fragility down the road that we were worried about (stuff like “corrupt registry). They just had to learn a new thing. Time passed. Everyone adapted.

I could repeat this for a half dozen other things. Changing the user interface for hundreds of millions of people using Office over decades was an even bigger deal with a massive pushback. That worked. Changing the Start menu for Windows, not so much.

I can say with certainty, success or failure feel exactly the same, carry the same dynamics, and attempting or succeeding at being disruptive comes at an enormous personal cost even though it is incredibly difficult. It also isn’t automatic. For example, iPod or every dot com failure, there are untold other failures and more, but far fewer successes, but the pattern is always the same.

Not everything is a disruptive change and it can be pretty lame to label everything and anything (from a startup or anywhere) as such. Certainly just applying that label isn’t an excuse to be rude in public discourse. In other words, the actions of disruptive behavior need support the broader disruption.

Therefore, when someone or some organization is trying to do something new and dare say taking on the role of a disruptor, recognize that the pattern will always be for others that see the change as a risk to tear down what they are doing. The disruptors will be broadly critical of what they intend to replace as they marshal the teams, ecosystems, and resources required. There’s simply no other way.

It is worth remembering this reality when being critical, harsh, or personal while the change is being attempted and put in motion. Ask yourself if your reaction is coming from a place of defense, a glass house, or maybe just reacting to the style of a disruptor trying something bold or difficult.

It is called creative destruction or disruptive change for those reasons.

I loved this post!

When you apply this analysis within the context of LLMs, what do you see as "halfway measures" between the world we exist in today, and a world that's much more LLM-first? I'd love to read more about how you think operating systems or digital platforms will likely change as the cost of LLM inference becomes "too cheap to meter".

Also, do you think that as society becomes more interconnected, it's becoming a lot easier for "disruptors" to disrupt various existing status quos? Or is it more likely the case that we can just see the dynamics unfold in real time, and so it "feels" faster?

Aren't humans caught between conflicting nature?

On one side we seek the comfort of familiarity (repeat orders, close friend circle). On the other side, we desire changes to feel good (new dishes, different government).