108. The End of the PC Revolution [Epilogue]

To be hardcore is to be wildly optimistic about what can be achieved tomorrow while harshly pessimistic about what works today. —The author

Welcome to the final installment of Hardcore Software. It has been an amazing journey in the 115 or so sections including bonus posts. I owe a huge debt of gratitude to those of you that have followed along the journey of the PC and my own growth and lessons. Thank you very very much.

I have a few more bonuses planned, including a compendium of Microspeak and a bibliography of books and magazines that I collected. For paid subscribers I will be sending out an update on how billing will end and for “True Blue” subscribers please expect an email on receiving your compiled version of the work. It’s not too late to order that and also have access to all the old posts. I will also be filling in audio for the first 70 posts in early 2023.

Hardcore Software describes a personal journey. It is also one that happened to coincide with the PC revolution—the early days all the way through the final days of the revolution. The PC still marches on, but it is different. The PC remains essential though is no longer central to the agenda of computing as it was. That is what I mean by the end of the revolution.

This post is free and comments are turned on for all Substack users.

Back to 107. Click In With Surface

Windows 8 was a failure.

Hubris. Arrogance. Lunacy. Egomaniacal. Pick any word to describe the product; it was likely used somewhere. No one knew, or felt, the weight of the product failure more than I did.

Nearly every successful Microsoft product had survived our it takes three versions to get it right modus operandi. Esther Dyson, a technology investor and journalist, writing for Forbes in an article “Microsoft’s spreadsheet, on its third try, excels” said “It’s something of an industry joke in the software business that it takes Microsoft three tries to get it right. There’s Windows 3.0, Word 3.0, and now Excel 3.0.” She wrote that in 1991, reviewing the third version of Excel.1

No Windows leader made it through the odd-even curse of releases, certainly not three major releases of Windows from start to finish.

My hope had been for a credible Windows 8 knowing we weren’t finished, which was standard operating procedure for new Microsoft products. We knew where we wanted to take the product over time—the hardware, the software, and the apps. But none of that happened. For reasons I still do not fully understand, for the first time I could remember Microsoft quickly and completely withdrew and actively erased Windows 8 in an almost Orwellian way—even Clippy preserved its dignity. I try to imagine what would have happened had Microsoft given up on Windows the first time, or Windows Server, Exchange, Word, Excel, or PowerPoint. All of those took multiple iterations to find product-market fit, to win both hearts and minds.

Requiring three versions was not a Microsoft thing. It is a product development thing. Even in a big company you must ship the first version—shipping a “V 1.0” (v for version) is always a miracle. Then you need to fix it and that was version 2.0. Then by version 3.0 not only does the product work, the sales, marketing, positioning, pricing, and more work. Product development is always a journey. Always.

With years of hindsight including the new mobile market, the PC market, and Apple, many of the initial problems with Windows 8 were not nearly as egregious as much of the commentary made them out to be. Or maybe the commentary was right and what was egregious was not that we made a product that did what it did, but that we made Windows do those things? Or perhaps we simply did it all too soon? Or that we, surprisingly, lacked patience to get it right?

There was commentary on me as a leader, as a person. I knew that was borne of immediate frustration and not enduring. That’s why I remained quiet and did not speak out in 2012 as I moved on to a new experience in Silicon Valley and working with entrepreneurs. I understood and even respected the emotion from where it came and the forces that produced it. Over time individuals who facilitated that commentary have since apologized directly. I was proud to be part of more than two decades of building products, processes, teams, leaders, and people—a culture—that were the highest quality, best equipped, and most talented at Microsoft in the PC era.

The problems we needed to solve with Windows 8 and Surface were readily apparent, as I strongly believed the moment we shipped. Nothing anyone wrote about either was surprising or news to those of us who had lived with the products. The commentary on the severity of the problems, and how and what to fix, was debatable.

Microsoft had become synonymous with the PC, but could it also reinvent the PC? That was what we set out to do. The problem was that the people who loved PCs the most weren’t interested in a new kind of PC. They wanted the PC to get better, but in the same way it had for decades—primarily, more features for tech enthusiasts and more management and control features for enterprise IT managers. They simply wanted an improved Microsoft PC from Microsoft—launching programs, managing windows, futzing with files, compatibility with everything from the past, and more like that. They wanted more Windows 7.

Instead, they got a new era of PC, a modern PC, from other companies, and it would be called iPhone, iPad, Chromebook, or Apple Silicon Macintosh and they would be okay with that. Today in the US, Apple’s device share is off the charts relative to any past. Apple holds greater than majority share of phones. Macintosh is selling at an all-time-high 15-20% of US PCs depending on the quarter. As for the iPad, the device loathed by so many who believed thinking about tablets was the underlying strategic failure of Windows 8, Apple has perhaps 500 million active devices and sells about 160 million iPads per year, or more than half the number of PC sales. The business and personal computing market is no longer the PC market, but vastly larger, and the only position Microsoft maintains is in the part that is shrinking relative to the whole and on an absolute basis.

The iPad is worth a special mention because of the tablet narrative that accompanied Apple releasing their product just as we started Windows 8. The iPad had a clear positioning when released—it was between a phone and a PC and great for productivity. It was an odd positioning considering it was precisely a large, but less featured, iPhone. Soon Apple would say the iPad was the embodiment of the future Apple sought. Since then, however, the iPad has been mired in a state of both confusion and poor execution. While taking advantage of the innovation in silicon and the undeniably impressive innovation in Apple’s M-series of chips, the software, tools, frameworks, and peripherals directed at the iPad have, for lack of a better word, failed. For all the unit volumes and significant use as a primary device, it has not yet taken on the role Apple articulated. I would not have predicted where they are today.

Jean-Louis Gassée, hired by Steve Jobs and former leader of Apple hardware and later creator of BeOS, had this to say in his wonderfully reflective weekly newsletter, Monday Note:

The iPad’s recent creeping “Mac envy”, the abandonment of intuitive intelligibility for dubious “productivity” features reminds one of the proverbial Food Fight Product Strategy: Throw everything at the wall and see what sticks.2

In competition it takes the leader to drop the ball and someone to be there to pick it up. Whether Apple truly dropped the ball with respect to the iPad or not, it is certainly clear that Microsoft in a post-Windows 8 environment was in no position to pick it up. That is a shame as I think Apple created an opportunity that might have been exploited.

Instead in the Windows bubble, as much as anyone might have wanted new features or improved basic capabilities, they wanted compatibility with all that had come before. Legacy applications, muscle memory, and preservation of investments were the hallmarks of Windows, not to mention the ecosystem of PC makers and Intel. Why question those attributes with a new release in 2012?

There was a comfort in what a PC was already doing and refining that while leaving paradigm shifts to other devices was, well, comfortable. Many saw the PC as both irreplaceable and without a substitute. Like the IT pros who knew the Windows registry, they were comfortable with their mastery of the product even if the world was moving on.

Unfortunately, what is comfortable for customers is not always so comfortable for the business. Without a dominant and thriving platform, Microsoft is like a hardware company or an enterprise-only software supplier—reliant on deep customer relationships, legacy product lock-in, pricing power, and big company scale to drive the business. Those can work for a time, and perhaps even bide time hoping to invent the next platform. IBM continues to prove this every quarter, much to the surprise of technologists who today don’t even know what IBM makes or does.

Windows 8 was not one thing, and therein lies its main challenge. Windows 8 was not simply a release of Windows, some new APIs, and a new PC. Windows 8 was a paradigm—it could not be disassembled into components and still stand. If we had just built a Microsoft PC for Windows 7 that would not have changed the trajectory of the business, just as we have since seen with hardware efforts. We already saw how touch on existing desktop software didn’t deliver. Moving from Intel to ARM without new software or worse just porting existing software was running in place at best and taking focus away from worthwhile endeavors at worst.

To shift the paradigm and to enable Microsoft to have assets and compete in some new way required an all-or-nothing bet. Everything we know about disruption reveals how companies do what they can to avoid those situations and try to thread the needle. I was totally guilty of aiming to avoid that.

The temptation to cling, or leverage depending on perspective, to the Windows legacy was constant. As I learned over every previous, and smaller transition, giving customers a little bit of the past—a compatibility mode or a way to opt out of changes—meant customers would take advantage it. The new product wouldn’t be new to most customers. With Microsoft’s decade-long commitment to supporting that new-old state, we would have been shackled to the very platform that was already in an anemic state—Windows and the APIs for apps, Intel and the ever-increasing transistor march, and an ecosystem of OEMs and ISVs focused elsewhere.

There were five hot buttons I felt weakened our all-or-nothing bet. There was no quick fix for these, even in hindsight. Worse, each proved more early than incorrect. In technology, however as I have noted several times in this work, early is the same as being wrong. People will debate these even as I write them years later. I think we will always have fun doing so. I certainly will. It is the nature of engineering to forever debate the causes and decisions that led to failure.

First, the Start screen clearly served as the emotional lightning rod for the release. It was, to some, as if we ripped the heart and soul from Windows. I didn’t see it that way, obviously. I saw a mechanism that had outlived its usefulness just as we saw menus and toolbars outlive their usefulness in Office, or even character mode decades earlier. Despite being there in the summer of 1995, I did not see the quasi-religious significance of the menu. I saw something that people had mostly stopped using—the taskbar, ALT-TAB, search, email attachments, and browser tabs replaced launching and switching programs. Tech enthusiasts, however, had many more programs, dozens of utilities, and elaborate custom configurations. I know because they sent us the screenshots in protest. I would posit today that most tech enthusiasts are using the taskbar and search to find and launch programs, exactly as we designed Windows 8 to work. I also think they would have been fine turning off their computers with the power button and would have survived not having shutdown on the screen all the time, though they would miss the chuckle from the timeless hilarity of Start -> Shutdown.

Phone app screens grew to become the way computer programs are launched and managed. They take up the full screen and they are super easy to navigate, unlike the Start menu, which even with a mouse grew increasingly finnicky and awkward. Apple’s home screen evolved to be more like Windows 8, including search and an All Applications view. Windows ultimately evolved to become more like a phone screen and far less like the formerly beloved menu, but nothing would have appeased people at the time. Nothing, other than providing (an option, of course, everything is an option) the Start menu back for “non-touch” or “Intel” PCs or something arbitrary like that—a compatibility mode. We had compatibility mode—it was Windows 7.

Second, the presence of the desktop in Windows RT, the version of Windows that didn’t run any existing desktop apps. Additionally, the desktop not being the first thing to pop up after starting any version of Windows proved to be “disorienting” in ways that were more reactionary than actual. From the first demo at All Things Digital when we were asked about “two modes,” I was not able to find the way to describe this feature. If a product requires explaining, it’s already lost.

On Intel Windows, we wanted to remove a level of indirection and simply have a place to start. The desktop, with its cacophony of uses, had become a hairball. It did not roam between devices well (due to screen size and contents), and the slew of uses as a file cabinet, scratch pad, dashboard, and program launcher made improvement impossible. Alas, it was viewed as sacrosanct and another place where the world was changing but disproportionately less so for power users. The move to phones, browser apps, cloud storage, and multiple devices relegated the desktop for most. We were just too early.

Third, on ARM we faced another challenge: Our own desire to ship meant we shipped a product that was knowingly incomplete. We simply had too many places to return to the legacy experience. Apple chose to hide those capabilities on the iPad until they were ready and perhaps that would have been a better approach for us too. We should recall that the iPhone shipped without copy and paste, and the iPad was literally a big iPhone with fewer built-in apps and no phone capability. We wanted to embrace the capability of the operating system without compromising quality, security, and so on. For example, the iPad had no files or file management capabilities, including using devices such as USB thumb drives, until 2017. We supported those out of the gate, but that sometimes required using the legacy desktop and explorer. We didn’t have time to build the WinRT file manager app we had already designed, as an example, or update everything in the Windows control panel. The vast ecosystem took time to move, but we had to begin a transition.

Many believed omissions presented a weird modality or duality. Our explanation that this was always how Windows evolved failed to satisfy or reduce perceived confusion. Windows carried the DOS box and command line (and still does) and even .INI files, for those who cared, for decades—and it was widely used by tech enthusiasts and administrators alike—even for copying files! Having some of the old along with the new had always been the Microsoft way. It just seemed so inelegant compared to Apple.

I, we, did not love that we had to do this. While we considered many alternatives, we didn’t have a better approach without taking forever to ship. The enemy of the good is the perfect. The industry was moving away from Windows, and we had to get in the game. That is decidedly different than Apple releasing a phone to a market that was far from settled and expected little from Apple which had nothing to lose. We had everything to lose and were losing everything.

Fourth, there was one very significant reason we required the desktop and why it was not simply a bonus like the old command or DOS box.

Office.

The shift to touch, phones and tablets, and a modern operating system with new apps was much larger than any one of those individually. To decompose the strategy into components is to wield the technology buzzsaw or fall victim to taking on disruptive technology shifts like entrenched incumbents tend to when failing. To have a viable product, we needed to execute on all, simultaneously.

These shifts happened all at once not because the PC did not take on each feature individually, but because the PC model itself could not possibly address the shortcomings that built up over years. Loosely aggregated features, engineered across adversarial partners, combined into a product was well-suited to the invention of the personal computer, but not the optimization of the experience. The idea that the PC could move forward into a new era by simply adding touch, or some new user interface features on top of what was there or adding an app store while still supporting downloading code from the internet, or even adopting ARM, each as a point solution was simply the old way of solving problems, the PC way.

Surface RT was designed to be the epitome of productivity for mobile information work. We wanted Surface to be people’s primary work computer, the way they used a laptop (PC or Mac), but with all the reliability, security, battery life, and mobility of an iPad. To accomplish that we needed Office: Word, Excel, PowerPoint, and (some would say) Outlook. The problem: I was not successful at evangelizing the new platform opportunity to the Office team. Let that sink in.

The hallmark of Microsoft’s strategy had always been apps and platform, platform and apps, and if necessary, by force. Early on the apps were forced to work on Windows against their judgment, and then later Windows was forced to be good for the apps even when it thought Office was not the focus, and this see-saw continued for the benefit of the industry. It was like we had reached a point where both businesses were so entrenched that their own worldviews precluded a bigger, all Microsoft bet. Perhaps we reached a level of fatigue in cross-company bets after the Longhorn and .NET eras.

When we presented the Windows 8 vision years before, I sat next to SteveB and friends from the Office team that were invited. It was during that meeting that we began to make the case that the new runtime existed to build new apps—new ways of working, focused on collaboration, sharing, tasks, cloud storage, and less on massive amounts of formatting, scattered document files, and so on. The collective questions were more about how to maintain compatibility for Visual Basic for Applications, third-party add-ins, and the Ribbon. We never bridged that gap. The whole product cycle, Office wanted to port existing Office to ARM and run it. The biggest irony was that the entire time the Mac Office team was busy building Office for the iPad, which is why it was ready to release on the heels of Windows 8. There are two sides to this story. The Windows 8 leaders knew both sides because we were previously the leaders of Office. There was a view that even that cross-pollination contributed to the challenges. Ultimately, there was a need for both the old Office and a new set of tools. Silicon Valley was hard at work creating new tools for information workers—modern, mobile, cloud, web, SaaS tools for productivity—while Microsoft continued to pay the bills with existing apps, even if they sold under the 365 cloud moniker for much higher prices.

Office was part of a symptom, a fatal symptom, of having no WinRT apps, which was obvious. Everyone in the industry knows that if Microsoft is serious about something then Office will participate. If Microsoft was not serious, then there was no Office support. Desktop Office sent the clear message that Microsoft was not serious about WinRT. It didn’t matter what we said as our actions spoke louder than words. We had OneNote and some experiments. But without Excel, there was no WinRT. We had many debates in executive staff meetings about juicing the ISV ecosystem. That whole ecosystem was focused on the browser while still suffering from the strategy fatigue from Windows Phone 7 (and soon 8) and the failed Longhorn strategies. We needed Office. We got OneNote. I still love OneNote to this day.

We chose not to build a phone first or simultaneously. Perhaps the entire platform strategy would have been different if we had indeed executed on the mythical plan of having a phone and first-party hardware out of the gate. Since that would not have finished perhaps until 2015, debating it at all might be irrelevant. By 2015 the world would be solidified around iOS and Android leaving little headroom for us, plus we would have had a couple of more years of failure of Windows Phone, services, and an aging Windows 7. Fans of Windows Phone will continue to debate and champion that legacy the way people fondly remember the Amiga or Newton, so this is one debate I intentionally avoid.

And fifth, Windows RT and even Windows 8 were the product names. Many argued that any product without a traditional Start menu and full compatibility could not be named Windows. More would argue that naming Windows RT as we did, “confused customers” as to what would run where. That was true, but Windows had long had variants that came with limitations or exceptions: Windows NT, Windows CE, Windows Embedded, Windows Media Center, even Windows 2000, and most recently Windows Phone. All of these were confusing in some relative sense, but all were given time to rationalize the confusion.

Should we have abandoned the legacy that was embodied in the Windows name? I certainly thought about that a lot. Here again, everything about disruption would have said absolutely name it something different. Heck, put the team in another building, get them new card keys, and so on like the Zune team did. That same theory also showed how no one ever does that because they look at the cost and effort, along with splitting all the energies of the company, and reject any such approach as heresy. As someone who grew up knowing that Windows NT or even Windows XP didn’t really run everything Windows 95 ran, I felt like we could pull it off. I was wrong. I don’t think a new name would have worked any better and would wager that any new name would have been cutesy and clumsy at the same time given Microsoft’s history. Then again, many chuckled at iPad too.

There were a host of smaller reasons as well, some related to timing and others to just trying to get a product to market. The original Surface did not support LTE, which undermined our mobility and mobile chipset message. We chose a unique aspect ratio for the screen, which proved to just be wrong for productivity. SteveB pushed on this as he personally began to like eReaders on Android that had paperback book aspect ratios. We all agreed, but it was too late. The original Surface RT keyboard, the Touch Cover, was innovative but not productive. There were other software aspects as well, like my refusal include Outlook, which would reduce battery life by 1-2 hours simply because it wasn’t a modern app and had incomplete connections to our services backend. The lack of support for traditional group policy irked IT Pros who felt they needed to secure any device using invasive methods used on PCs. Those methods were battery draining while opening up a host of Win32 compatibility requirements. Modern mobile device management tools are far better than what IT did at the time, and we built those capabilities into the first release.

I tend to look at the failures of the product strategy because that is where most of the focus sits. But I had failures in the go-to market as well. I am rather fond of pointing out that success and failure are elements of the 4 Ps of product, price, place, and promotion. In the case of Surface RT, we got the price right assuming we sold a lot of them, and surprised some people even in the face of super cheap Android tablets. We got the place, the distribution strategy, entirely wrong. The Microsoft Store retail team was insanely excited to have exclusive access to Surface, but there weren’t enough stores to sell the number we needed or wanted to sell. I was unable to make the math clear to leadership. We literally could not sell all we made even if the stores operated at multiples of capacity, 7 x 24. I begged and pleaded to expand distribution, and so did our partners, right up until the end. In the process we angered our Windows retail partners around the world. Then we had a whole bunch left over, and in 2013 Microsoft took an inventory write-off to complete the erasure of Windows 8 from memory. I remain convinced, perhaps naïvely so, we could have moved many more units had we opened the retail strategy. That would have allowed for the potential to iterate to a second and ultimately third version.

No matter what happens, someone always said it would, and when a product fails those predicting that are quick to make themselves known. I admit I found it enormously frustrating to see the revisionist views appear, whether with the press or with people at Microsoft. President John F. Kennedy famously said, “Victory has a thousand fathers, but defeat is an orphan.” I certainly felt alone in defeat. It is well-known that as a leader, a huge part of the job is to stand alone and absorb the defeat. I think I did that at least as well as making sure any successes achieved over decades were those of the team or specific individuals and definitely not mine alone.

While our issues are quite clear in hindsight, they were also visible at the time which only serves to further the told-you-so reactions. Every technology shift had doubters focusing on some specific issue, or challenge, rather than seeing a complete package like all those people who said the Macintosh was not a real computer because of the mouse, or how the iPhone touch screen would not work. Had the iPhone failed, it is easy to imagine the self-congratulations from those who noted in their reviews the lack of copy/paste, missing Adobe Flash support, incomplete push email, or the new on-screen keyboard.

I knew the feedback on each of the specifics, but also, and naïvely, hoped the whole system could be seen for what it was trying to do…and it would do if given a time and effort. The story of the ribbon in Office, one of the biggest and most successful UI reinventions undertaken in a product, was one filled with doubters inside Microsoft and outside as we discussed. Today some of those who were the most negative about the change even find themselves leaders in today’s Office.

But why should people have been patient? They had the iPhone, iPad, Android phones and tablets, and Chromebooks all to choose from. They were happy to use those and just stick to Windows for all the familiar legacy work.

As we progressed to the October 2012 launch of Windows 8, a lot was happening that perhaps marred our ability to see clearly and, more importantly, collectively. It was an anxious time. We spent the summer in leadership team meetings gearing up for the yearly sales meeting ahead of a big launch year. The past ten years of flat stock price and lackluster product success had taken its toll.

The difficulties with Windows Phone were compounding, despite poorly grounded optimism. Phone apps were not gaining traction and worse the hacks to gain apparent traction were backfiring, such as paying developers to write apps or adding apps to the store that were simply web sites. Fingers were pointing. With Surface, the question became: Should we build our own phone? Should we kick off a skunkworks project like Zune (that team was available) to build a phone? Would that truly address what we were seeing in the market? The phone was the next platform, a platform for the entire planet, and we were not even registering as a viable third place. The opportunity to align Windows and Windows Phone long passed and there was still no appetite to weigh down the phone strategy with a full Windows-centric approach. It was always as if the phone was on firm footing, and it just needed to borrow a bit more code from Windows. It was never on a path to success.

The Windows Server team seemed to resist embracing the new Azure product, which remained organizationally distinct. In hindsight this proved reasonable as Azure came to be dominated not by Windows as hoped but by Linux. We were obligated to support them, so that was creating a lot of extra work for us, delivering for both the on-premises server and the new data center product. The enterprise server and server apps data center era, as we knew it, was over. It was archaic and unmanageable. Microsoft was barely able to keep its own Windows data center running. The future of the server business was the cloud, but our enterprise customers were strongly resisting, or more likely entirely unaware, of that fact. AWS was still almost entirely a Silicon Valley novelty. This made it easier to ignore.

Our commitment to online services, what I saw as a key component of the Windows platform as we knew it, from communications to identity to storage, were all seen as cost centers despite the obvious need to own and build widely used cloud services across devices. A complete device experience required services extended to the cloud, built natively for the cloud rather than ports of existing Windows and Office servers. The device experience as we knew it to be was coming to an end without services.

Microsoft’s transformation to an internet company—well documented as one of the most successful pivots of all time—turned out to be great for our revenue but lousy for our platform technology. The level of internet savvy across the company paled in comparison to Google and Facebook (yet the much-sought-after Yahoo rapidly faded). Little, if any, Microsoft technology or platform were part of the rise of these huge new powers. The only organic internet scale business was Bing, which continued to struggle, though ironically has today found a niche disguised as the anti-Google DuckDuckGo.

Across Office, Windows, and Servers, the reality was our pricing power, distribution moat, and enterprise account relationships combined to provide comfort in the face of shifting platforms. The reality of business disruption was right in front of us. It was plain to see. Yet the business was apparently thriving, just as the classic book on disruption would predict.

Despite the massive revenue success and great numbers, the technology story looked bleak to me. I felt alone in that concern. I sent a memo to the leadership. It was a plea to develop a point of view that these technology shifts implied that went beyond defensive—Without a Point of View, There Is No Point. I tried to argue that we had been lulled into a sense of complacency by having succeeded through the dot-com bubble yet ended up weak in every technology shift that followed. We were losing everywhere, except revenue. We did not have a platform, which as a platform company was a big deal. My memo, which turned out to be the last one I wrote, was decidedly a polemic meant to stir people up.

I also wondered whether it even made sense to keep score, so to speak, with products and technologies. Maybe all that mattered was leading by business metrics like revenue, profit, and cash flow. There are worse things than being a huge money-making corporation.

Leading Microsoft to reimagine Windows had been accomplishment enough for me. I knew what I had signed up for more than five years earlier. It was much more than even I had planned on. But it was time. Ultimately, I could not break the odd-even curse.

After the October launch in New York, it was time to mark the end of my career with Microsoft. With great clarity, I knew it was time to use that resignation letter I’d been holding on to. One last meeting with SteveB, and some quick rounds across my direct reports, and then I hit send. Our split was undeniably mutual. I felt a sense of relief. Compared to leaving the Office team for Windows, I was much more certain this was the right decision. I was eager for a context switch.

Once the decision was made, moving on immediately was best. I never wanted a big send-off. Quite the contrary. I had gone through two years or eight depending on how one counts of Bill “transitioning” (not that there is a comparison). Then there was the year transitioning through Windows Vista I experienced. I’d seen too many people stick around for too long, confusing the team and dragging their departure out.

What I failed to understand, and deeply regret, was that in our collective haste to move on I left behind the most superb team, ready to take over and move things to the next level, but not prepared for what would actually follow. I was selfish and the people who gave the most to create the new Windows team paid for that.

The “post-Sinofsky” unwinding of Windows 8, not just the product, but the organization and processes as well, became even more painful than market reception of Windows 8. I let the team and my best friends down. I left them to pick up the pieces I should have been picking up myself. The management above them failed to show them the respect they deserved. Nearly every one of them represented in these half-million words—the best leaders Microsoft created across every discipline—has left the company. So many of them are creators, entrepreneurs, and thought leaders in ways that Microsoft does not even participate today.

BillG had always been fond of saying that tech companies have a remarkably difficult time leading as technology crossed generations. Leaders of each era might maintain scale, rarely evaporating, but losing influence and presence in the market. Technology analyst and friend Benedict Evans wrote:3

Every day of Windows 8 development, I worried about losing our audience of developers who hung on every word of not just what new features for Windows and Office were being shipped, but what code they could write, what business they could build, what customer problem they could solve by making a singular bet on Microsoft’s inventions to power them. I’d seen the relevancy of Office fade even while the business grew. Many companies have core fan bases, but Microsoft was blessed with people and companies building businesses on our technology, uniquely and singularly, and many of them moved on. Developers are not the end, but a means to a force-multiplying economic relationship with billions of people. I’d seen how easy it is in a large organization to find a bubble to hide out in—a bubble where our products are as popular and relevant as they once were.

Paul Graham, fellow 1980s Cornellian, founder of the Y Combinator startup accelerator, and described as a “hacker philosopher” by author Steven Levy, wrote two essays on Microsoft that were rather prescient, if not spooky. They were written so early as to be easily dismissed or perhaps wishful thinking. In 2001, he wrote “The Other Road Ahead” a nod to the book by Bill Gates. In this essay he described the new Web 2.0 paradigm relative to the desktop computer. He aptly described the bubble Microsoft was in, that I was in, and we just didn’t know it:

Back when desktop computers arrived, IBM was the giant that everyone was afraid of. It's hard to imagine now, but I remember the feeling very well. Now the frightening giant is Microsoft, and I don't think they are as blind to the threat facing them as IBM was. After all, Microsoft deliberately built their business in IBM's blind spot.

I mentioned earlier that my mother doesn't really need a desktop computer. Most users probably don't. That's a problem for Microsoft, and they know it. If applications run on remote servers, no one needs Windows. What will Microsoft do? Will they be able to use their control of the desktop to prevent, or constrain, this new generation of software?4

The essay is long and well worth reading for its predictive powers. While not every technical point landed precisely as described, especially the iPhone and apps, it is a brutal read that was aptly ignored by us at the time. As if to double-down, in 2007 he wrote another essay “Microsoft is Dead” wherein he described what took place in the mid-2000s that killed Microsoft. This was just after Windows Vista when it was easy and rather popular to assert an end. That was because of Vista, however, not because of the four factors in his essay: Google, the desktop is “over”, broadband internet, and Apple OS X on new Macs. He concluded with a candid and brutal take:

Microsoft's biggest weakness is that they still don't realize how much they suck. They still think they can write software in house. Maybe they can, by the standards of the desktop world. But that world ended a few years ago.

I already know what the reaction to this essay will be. Half the readers will say that Microsoft is still an enormously profitable company, and that I should be more careful about drawing conclusions based on what a few people think in our insular little "Web 2.0" bubble. The other half, the younger half, will complain that this is old news.5

Despite Graham’s dire predictions, people continue to rely on Microsoft and bet on the company today. Microsoft is an enormous business. It is undeniably a different kind of leader, more a comfortable companion than a guide taking you to new places.

It is popular to say that the operating system is no longer key, that the definition of a platform has changed, and that the battle is now above the OS. That’s a great rationalization, and as Jeff Goldblum’s character in The Big Chill said, “Don’t knock rationalization. Where would we be without it? I don’t know anyone who can go a day without two or three rationalizations.” The biggest business at Microsoft remains Microsoft/Office 365, and as valuable as email and video conferencing are (and as important as transferring the capital and operational costs to Microsoft in exchange for a huge price increase was too), the unique intellectual property in Office 365 that defies competition is Word, Excel, and PowerPoint. These remain key tools used in daily mission critical work by perhaps 300 million information workers. Those people, at least 90 to 95 percent of them, rely on Windows to do that work, which is Microsoft’s second largest business.

Bundling the new Microsoft Teams with the 365 service perfectly reflects this legacy approach, a well-worn strategy to support the existing business and pricing rather than risk building a new business and creating a new revenue stream. In this work I described the bundling of Outlook, OneNote, SharePoint in this same regard during the expansive period of enterprise software. Microsoft loved a good bundle. Customers did to. I suspect this time with Teams will end differently primarily because the computing world is in a different place and the requirement that customers settle for a bundled product is nowhere the same as it was in the early or middle stages of the PC era. Certainly, the macroeconomics of 2022 will provide a foundation for a bundle, but that has not proven sustainable.

The virtuous cycle of apps and systems envisioned by BillG in the 1980s stands as the hallmark of Microsoft, but it is not growing in users and is not part of a thriving ecosystem. New customers aren’t coming to PCs with Office even at a rate to replace those that retire. Windows PCs are not benefitting from advances in a hardware ecosystem that transitioned to mobile. Developers aren’t building new software for Windows. The cycles have been broken.

PC sales in 2022 will likely have declined 15-20% over 2021. Many will point to the economy or foreign exchange rates or length of a replacement cycle, or maybe even Apple’s inability to figure out its own product strategy. At some point the only conclusion is that the PC, like the mainframe, minicomputer, and workstation before it, was a mature and saturated market. There will be good years and not so good years, but the PC or PC server running Windows will never be the platform it was. Even if people develop new products on it, those products will not take advantage of what a new PC has to offer, which is the definition of a platform.

The web and smartphones have assumed the role of the information platform for the world. This time is different, however. Together these two have touched every human on the planet. That hasn’t happened with any other foundational platform, to use the term broadly, in history except for perhaps fire. All the amazing, connected platforms from the 20th century reached their limits long before reaching every person everywhere, including rail, car, roads, airplanes, telegraph, telephone, television, electric grids, sewage, and more. Whatever comes along next will also be the greatest technology displacement in the history of humans as it will replace the internet-connected smartphone for every person on earth. That is going to be an incredible innovation.

Craig McCaw, one of the earliest pioneers of mobile phones in the US via his namesake company and graduate of Seattle’s Lakeside School a few years before Bill Gates, described humans as inherently nomadic when it comes to the technology they use. He first made this observation with respect to mobile phones compared to land lines that tethered users to a wall.6 Technology is broadly adopted first when it meets their needs, and not before. Then over time when a product fails to meet their needs and something better comes along, they simply move on. Smartphones came along and when they became good enough, people simply stopped demanding new PCs.

BillG once said to me of another legendary company facing challenges that things always seemed brightest before a precipitous decline. That’s what Windows PCs were facing. Windows 7 was peak PC the way Office 2007 was peak Office. Peak, not in terms of financial success, but peak in terms of influence, centrality, excitement, and general interest. Microsoft was in the midst of disruption, to use that overused phrase on more time. Not everyone agreed about where we were in the arc, and that was the problem.

Either way, it was the end of the PC era.

We knew that because we could read, watch, or hear about it all by swiping with a finger or by asking about it on that modern computer in our pockets or one of the hundreds of millions of tablets on sofas, in the back seats of cars, or in airplane seats. That computer was the reinvention of the PC. In no shortage of irony, the company that brought us this new computer was Apple—the company that for all practical purposes invented the PC in the first place.

Windows PCs are never going to reach 500 or more million or more units a year as analysts had once predicted. The question was not how high sales would go but how low could they fall—peak PCs ended up being the Windows 7 upgrade cycle that resulted from a combination of poor demand due to Windows Vista, delays due to the recession, and lengthening PC lifetimes. A market of 300 million PCs is a fantastic business (about the same as 2007), but it isn’t two billion iOS devices in use or the more than three billion active Android devices. It certainly isn’t the growth opportunity of bringing PCs to every home and desk across emerging markets in Asia and Africa like we had hoped a year or two earlier.

Did Windows 8 cause PC sales to decline because it was the wrong product for the PC? Or did the substitution of phones for PCs in the eyes of customers cause the decline in PC sales which made Windows 8 the wrong product? Years later all I can say with certainty is that those both happened at the same time, each correlated with the other. Importantly, would a more incremental and traditional release of Windows have really saved PC sales or even have spurred significant growth? Does anyone really think this today? I didn’t then and certainly do not today.

Looking back, there are small things that I might have changed, though I can say with confidence that would not have altered the outcome. To date, no one has offered up a plan that would have had a better shot at helping Microsoft achieve the same level of impact and influence in this next era of computing. It makes for a fun column or Gedankenexperiment to explore the counterfactual, but I didn’t really have a way to do that in real time. There’s no A/B test in building Windows.

Microsoft was going to be big for decades the same way IBM had remained significant, but it deserved its chance to earn a spot as influential and central a platform to computing as it had been originally. The most obvious answer is also the most difficult for me to accept, which is maybe there just wasn’t a plan. Maybe, unfortunately, where the world settled was inevitable. People moved on.

It is easy to poke holes in this sort of logic. We were not caught off guard or in denial. This was not New Coke. We did not see that the youth market liked a slightly different PC, so we tried to tweak the PC to make it more stylish and appealing. Our strategy was similar to what Apple had done, though our approach brought our unique perspective. There was a clear case of parallel evolution, but Apple came to market first (again!) and there were many reasons to believe being second would have advantages, as had been the case for the PC, Windows, Word, Excel, Windows NT, Exchange, and so many other Microsoft success stories. That was not the case.

When I look at the Tablet PC, Media Center, Windows Phone, or a host of other products, one thing is clear. Those products did not have the right substrate relative to how the market would evolve. There was nothing in those implementations that represented a first step in a progression to the products that did eventually dominate. It is fair to say the concepts were right, but the technical foundation was wrong because elements were simply not ready. Windows 8, in my biased view, had the right ingredients that were also market-ready.

There is one exception to Windows 8 having the right ingredients, and I don’t know if the market gives Apple enough credit for what they have done. The Apple Silicon work is, at least for now, unparalleled. There was no likely outcome over the past decade that I think would have left Microsoft and likely NVIDIA in the position to compete with Apple Silicon, though a stronger Microsoft might also have influenced how Apple evolved. Apple Silicon was really in Apple’s DNA from the earliest days and was almost an inevitable outcome of the failure of Motorola, PowerPC, and then Intel to contribute to what Apple saw as its destiny. I look at that work and wonder how we might have responded because we most certainly would not have gone down that path. It was one thing to assemble the components and PC and bring it to market. It would have been quite another to have the audacity to create a chipset.

Since leaving Microsoft at the end of 2012, I’ve spent many hours discussing and debating the specifics of Windows 8 with friends, former coworkers, current employees, start-up founders, reporters, and, well, people who are just curious. Most of the time is spent discussing platforms, ecosystems, and tectonic shifts that one faces after unimaginable success, at least when we’re not just tackling my favorite topic and the bread and butter of Silicon Valley, which is growing and scaling innovative companies and teams. There remains a desire, especially among the reenergized Microsoft community, for more about specifics on the perceived misdirected product choices. In many ways that discussion is both easy and impossible. It is easy because there are only a few things to point to. It is impossible because if the situation could have been so easily addressed by changing something that was so readily identified, then that would have made for a quick fix.

Maybe wanting so much more for Microsoft’s products was the bigger mistake, more than changing the Start menu or breaking with legacy compatibility. That apocryphal Henry Ford adage about cars and horses was meant to point out that people express their needs relative to what they understand the possible solutions to be. Windows customers wanted Windows, a faster Windows, but they didn’t want something different…until they did.

There’s an old USENET meme used to make fun of seemingly trivial problems by claiming something is the “hardest problem in computer science.” It might very well be that the actual hardest problem in computer science is a company reinventing its own successful computing product for a new era in a way that existing customers are willing and excited to use. The irony is that those same customers always seem willing, and excited, to jump to the next era of computing using products from another company. Maybe that is a net positive and it is nature’s way of restoring, even rebirthing, our technology foundation.

The impact of Windows 8 and the way Microsoft chose to move on so quickly did have one important and chilling effect. Not only did so many people leave or were made to leave, but the culture that replaced them became risk averse and one that rewarded not failing more than taking risk. There was a fear of repeating a Windows 8, whatever that might have meant. For all the focus on growth and the ever-rising stock price, that meant growth of revenue more than new customers, scenarios, or business approaches. Soliciting feedback, voting on features, listening to customers, or creating products for all platforms are not substitutes for a point of view or strategic moat, as our industry has shown time and again—as counterintuitive as that might be.

A decade has passed since Windows 8 and product releases from the company have done little to avoid the IBM fate, a fear of which BillG firmly implanted in my psyche.

Half will read that and mock me for suggesting any of it and that explains all that’s needed to understand the failure of Windows 8. The other half will read that wondering who IBM was and when exactly they mattered. I started my career when IBM cast a shadow over every aspect of the technology industry and was fortunate to experience when Microsoft rose to that position. Bill instilled this very fear into all of us even before the internet or the split with IBM.

Ibn Khaldun, an Arabic philosopher during the Middle Ages, wrote that in war “the vanquished always seek to imitate their victors.” In business it is often the other way around. The victors end up becoming what they vanquished, as victors inherit the same problems on a new technology and product base. It might take years, but creative destruction is just as certain to take place. My Harvard Business School friend and previous co-author Marco Iansiti once joked to me that the school considered rebranding disruption theory as physics or math, not simply theory.

Despite how the product landed and then crashed, Windows 8 was the most committed, skilled, and brilliant Windows team ever assembled and it had one mission: to give the PC a new direction for a new world. Ultimately, under my leadership and management we failed to build a product that would change the trajectory of Windows or PCs. We failed, however, with elegance, grace, and an amazing group of people doing their most memorable and rewarding work. Unlike many failed efforts at Microsoft, we had remarkable execution. Like many failed efforts at Microsoft, we had the right ideas but the wrong timing. The Windows market wasn’t ready, but when it was ready, Microsoft was too late. Windows 8, therefore, was both too early and too late.

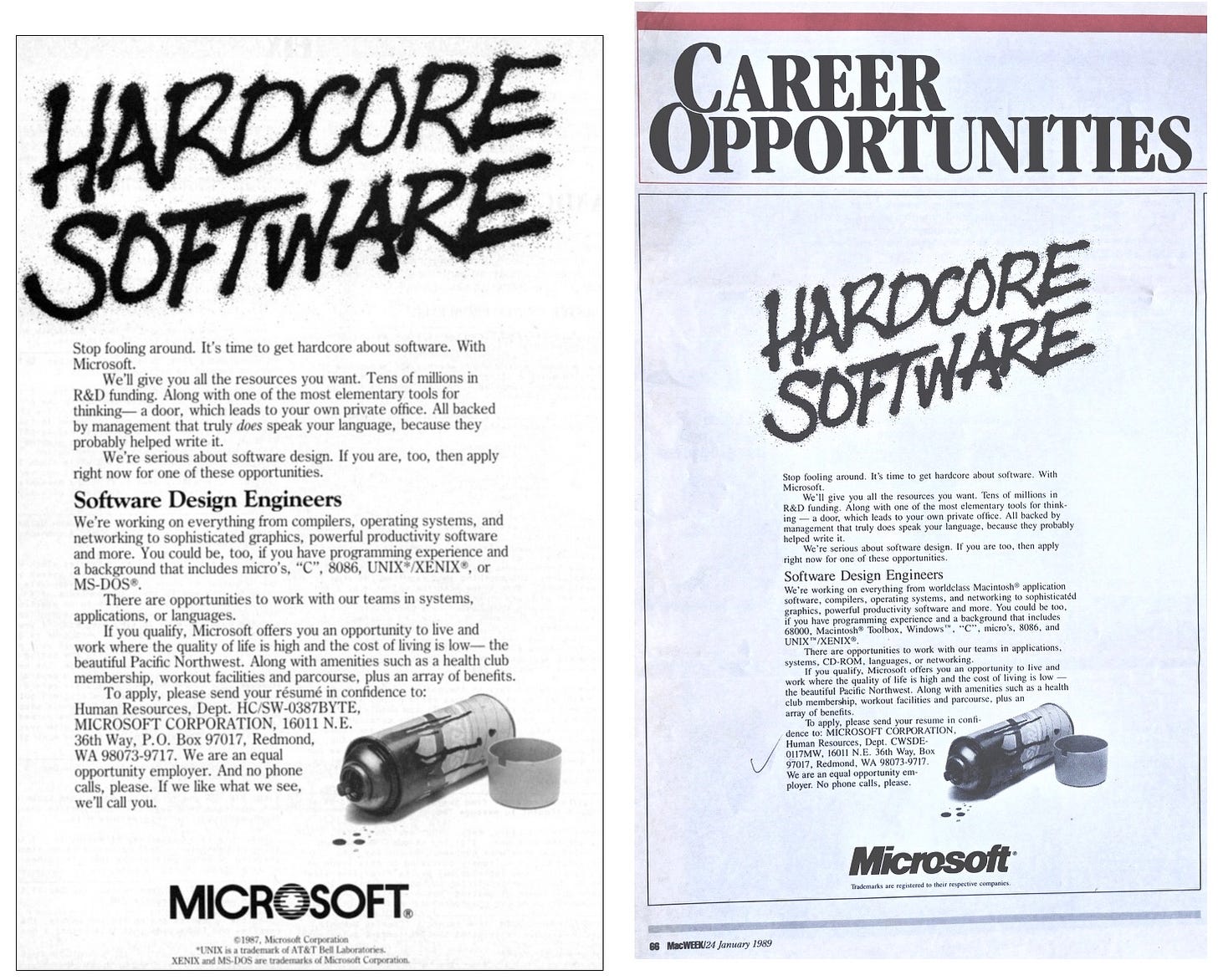

Windows 8 was the last product to be made by Microsoft’s definition of hardcore software. Some will say that is a good thing. It is neither good nor bad, but simply is. It is how eras evolve and the torch passes from one generation to another.

I was attracted to Microsoft by the level of product and technology acumen of every single person I spoke with all the way up the chain to the founder and CEO, the office with a door, the free drinks, and the Pacific Northwest. What really got me was what I saw as the true nature of hardcore software.

To be hardcore is to be wildly optimistic about what can be achieved tomorrow while harshly pessimistic about what works today. Creating software is an art. It is computer science and engineering. It is inspiration, and perspiration. It is inherently individual yet relies on a team. Most of all, building software is a group of people coming together to conjure something into existence and turning that into a product used by billions.

And that is Hardcore Software.

Forbes. Dyson, Esther. (1991, April 1), Esther Dyson, “Microsoft’s spreadsheet, on its third try, excels.”

“The iPad Mystery. New Episode: Food Fight Strategy” by Jean-Louis Gassée, November 20, 2022, mondaynote.com/the-ipad-mystery-new-episode-food-fight-strategy-1aa7b11dfa7a

via twitter @benedictevans benedictevans/status/1127280727475679232?s=20

"The Other Road Ahead" by Paul Graham, September 2001, www.paulgraham.com/road.html

"Microsoft Is Dead" by Paul Graham, April 2007, www.paulgraham.com/microsoft.html or the abridged version “Microsoft Is Dead: the Cliffs Notes”, April 2007, www.paulgraham.com/cliffsnotes.html

“Billionaire McCaw, Unfazed by Flops, Backs Wireless Internet” by Peter Robison, February 23, 2005, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2005-02-24/billionaire-mccaw-unfazed-by-flops-backs-wireless-internet

I've been a little dismayed by some of the recent sections as the considerations were more rarefied than my limited and idiosyncratic experience. For starters, I liked Windows 8 and was gratified when (with 8..1?) I could start on my desktop. And I loved the Start Page. I still use it on Windows 10.

I also have three icons on my desktop. They are named Shutdown, Restart, and Logoff and have appropriate images. They fire up shutdown.exe with appropriate command-line options :).

Having an invite to the Microsoft Store as part of a workshop on the campus, my favorite T shirt is the one with "backward compatibility" in mirror image. OK, the OpenBSD wire-frame image of a puffer fish is also favored.

There is no doubt I am not in the essential demographic. Having keyboard, mouse, and a 30" monitor is demonstration enough. That I still want to provide tutorials on the use of CL.exe and Native Build Tools is further confirmation.

And for me, the death-knell is Windows 11 which cuts me off at the knees as a consumer.

I began with software in 1958, and I clearly remember the IBM umbrella (or confinement dome), the failed interruption from Burroughs, and other experiences. I watched Sperry Univac fail to understand that virtual memory was here to stay despite the failure of the 360/67 project and so were caught short when every 370 had it. Xerox failed at a time when their proprietary silicon was ill-equipped to contend with Intel and Motorola, although it is probably more relevant that the company business model and DNA were ill-suited to a commodity "office of the future." Desktop PCs disturbed the mainframe enterprise world in much the same way as the smartphone has broken the desktop tether.

I have had the pleasure of watching Raymond Chen knit and also have Grace Hopper know me by name. I am forever grateful to have met my contemporary, Donald Knuth, in 1962 when he had a contract to write a book on programming, and I learned how much art can be seen in watching him code. Knowing Peter Landin led to interests and insights that I continue to pursue.

At 83, I might outlive the PC. Either way, I too shall pass. In many ways, it has been a great time to be alive in the upbringing of the ubiquitous computer and many other technological advances. May human nature thrive despite the unintended consequences.

I loved this series, especially the Windows 8 related content. Having worked at Microsoft from 2001 to 2013, it was interesting reading the “behind the scenes” stories of the various decisions and challenges. Thanks for the journey Steven!