093. Netbook Mania

"The PC industry is poised to sell tens of millions of small, energy-efficient Internet-centric devices. Curiously, some of the biggest companies in the business consider this bad news."—NYT 7/21/08

The Windows team was plugging away on Windows 7. The outside world was still mired in the Vista doldrums. Then in the summer of 2007 there was a wakeup call in the announcement and shipment of a new type of computer from upstart Asus, called a Netbook, a tiny laptop running Linux and a new chip from Intel. Would that combination prove to be a competitive threat or a huge opportunity for a PC world fresh off the launch of the iPhone?

Back to 092. Platform Disruption…While Building Windows 7

When a project like Longhorn drags on, the business is going to miss important trends. The biggest trend in computing in 2005-06 was expanding the PC to the rest of the world, something Microsoft and others called “the next billion” as the existing computing model reached approximately one billion of the world’s 6.5 billion people.

To outfit the next billion, many believed a new type of computer was needed. They were right. Many places where we would have liked to bring computers to the next billion lacked reliable electricity, air conditioning or heating, constant high-speed internet connectivity, and often had dusty environments as in Africa and much of Asia where I happened to have some of experience.

At the MIT Media Lab, Nicholas Negroponte, the lab’s founder, spearheaded a project called One Laptop Per Child, OLPC, that launched at the Davos forum in 2005. The rest of the world would come to know this as the “$100 laptop” at a time when most laptops cost about $1000 or more.

The price of $100 seemed absurd given that was less than an Intel processor and only marginally more than Windows, and that was before the rest of the hardware. Therefore, the initial designs of the OLPC would ship without commercial software from Microsoft or hardware from Intel. Instead, partners from anyone but Wintel lined up to help figure out how to build the OLPC. Almost immediately, Microsoft and Intel were blocked out of the next billion.

The resulting device, a product of some extremely fancy, perhaps fanciful, industrial design was a key part of drawing attention to what became known as the OLPC XO-1. The device featured several technical features that were aimed at solving computing needs for children in remote areas while also addressing the goal of ultra-low cost. The software was open source with a great deal of influence from historic MIT projects aimed at learning computing and programming. The effort even created a non-profit where people could go to a web site and donate the price of a device to have one distributed. The OLPC XO-1 was so cool looking that many people wanted one for their own use, right here in the US. The rollout and communications were exactly what you’d expect from the Media Lab—exciting and broadly picked up.

Microsoft through the Microsoft Research team and Craig Mundie (CraigMu) leading advanced technology spent a great deal of effort attempting to insert Windows into this effort. The company made progress but at the expense of causing some well-known members of the OLPC project to resign once it became clear that proprietary software was involved. Microsoft for its part would embark on the creation of a version of Windows that was ultra-low cost and stripped of many features as well, called Windows Starter Edition.

If there’s a theme in this work, both from Microsoft and MIT, it is that the core idea was that to bring computing to the next billion, products would need to cost less out of necessity and therefore they would need to do less and be less powerful. Often in the process of doing this the products would also go through transformation to make them easier to use, because apparently that is something required too. This is a fundamental mistake made time and again when addressing what the financial and economic world call emerging markets. Individuals in emerging markets do not want cheap, under-powered, or worse products. They certainly do not need products that are dumbed down. In technology, there is really no reason for that as products do get less expensive over time. Yet in the immediate term companies get stuck with their existing price structures and economics. And people in emerging markets are not less smart, they simply do not have access to the money for expensive products. I saw this dozens of times visiting the internet cafes in the most rural and economically disadvantaged parts of the world where students had no problems at all using a PC connected to the internet.

Microsoft would really get stuck in China where the limiting factor wasn’t hardware. People were buying huge numbers of PC components and simply assembling their own desktops that were on par with anything available from Dell or HP. They weren’t running Linux or Open Office, they were just pirating Windows and Office. The Windows team (I was still in Office) created a whole group to strip down Windows XP and add a shell to make it “easier” for emerging markets, again a dumbed down product. These changes to software were as much as way to make products favorable to the new markets as they were to make the product unfavorable to existing customers. Eventually, Microsoft came up with a plan to offer Windows plus Office to emerging markets, and China, governments for a very low price, so long as the computers were purchased by the government. At $3 per license this sounds like an incredible deal, but in all honesty was not that different from prices in many developed markets.

Still, the idea that the next billion required much lower priced computers, and somehow the rest of the world did not, would not go away. The need to serve this market drove the next wave of innovation from Microsoft and Intel, much more so than serving existing markets.

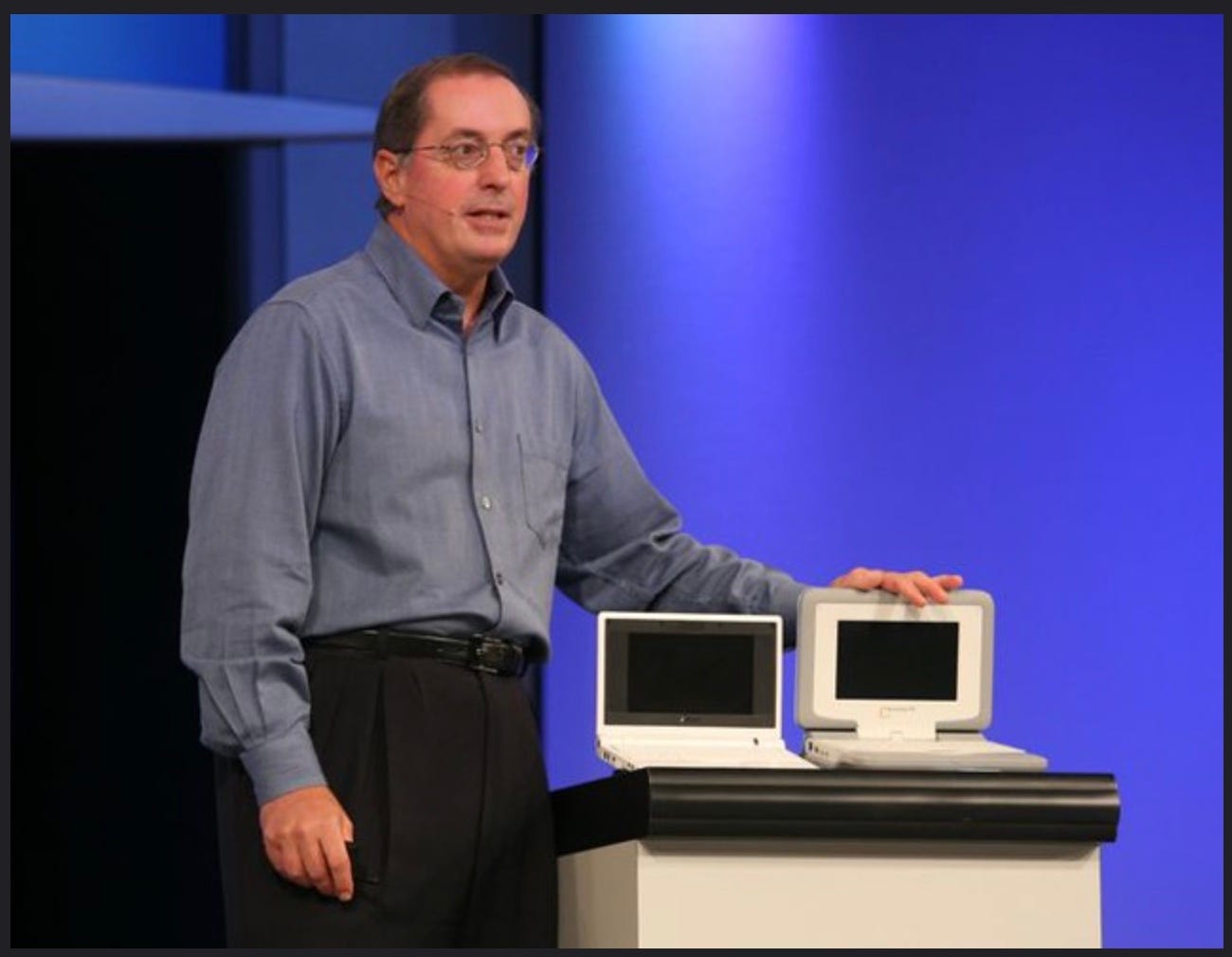

As Intel was mostly left out of the OLPC project, at the Intel Developer Forum in Fall 2007 they announced a new line of microprocessors with at least some emphasis on making lower cost computers for an expanded market. Intel demonstrated this processor in what is called a reference design, a PC made by Intel as a way to influence their customers to build similar PCs. The Classmate PC was a pretty cool looking laptop somewhat influenced by the Apple iBook, which brought the rounded edges, colors, and translucency of the iMac to a laptop form factor. Some would say the iBook itself owed its design lineage to the Apple eMate, based on the Newton, and sold to education markets in the 1990s. As a reference design, the PC shown could support a variety of screen sizes, storage capacities, and more, so long as it ran a new Intel low-power chip.

Also showing off the new chip in the 2007 Intel Developer Forum was the Asus Eee PC—that’s a lot of e’s, which stood for “Easy to learn, Easy to work, Easy to play” according to the box. The Eee PC was the first Netbook. It was also one of the smallest computers on the market. While there were many previous attempts at super small computers, such as the Sony PictureBook and Toshiba Libretto, there were years earlier and premium priced. This form factor and price were unique at the time. The first Eee PC 701 had the most minimal hardware specifications in any PC around and ran customized Linux and OpenOffice. It also had several games and entertainment apps.

The laptop was physically tiny as was the keyboard at 8.9 x 6.5 x 1.4 inches and under 2 pounds. It had a 7-inch display running at 800x480 pixels. For storage the Eee PC had only 4 GB of solid-state disk (like an iPod) and just 512MB of RAM. The price was $399 when it finally made it to the US, though the initial reports were it would cost $189-$299. It is worth noting that the same Intel chip was also available at retail stores in a laptop with a 14” screen, 80GB drive, a DVD drive, and 2GB RAM for about the same price. This reality would not distract from the cool factor or that it fit in any messenger-style bag.

The software load was kind of a mess, at least I thought so. The hardware, however, caught the attention of tech enthusiasts who were quick to turn the Eee PC into a tuner platform, looking to modify and replace components. Soon, modders were replacing the storage or adding more memory. There were web sites popping up devoted to modding the Eee PC.

The device sold quite well through the holiday of 2007 and that got our attention. So did the fact that modders were doing their own work to strip down Windows XP (from 2001) and squeeze it on to a 4GB system. One such modder was Asus itself which came to us wanting to officially modify Windows XP. There were three problems. First, they wanted Windows XP to cost the same as their Linux, which was $0. Second, they wanted to remove a bunch of XP just to make room on disk. What they wanted to remove was simply anything that took up space. It was kind of a free-for-all that reminded me of what enterprise customers did to Windows 3.x and Office 4.x back in the 1990s to squeeze on to 20MB hard drives.

The third problem was significant. Windows XP was done. We were over it. It was already seven years-old and we released Vista months ago. Vista was our bet. There was definitely no way Vista could be squeezed down, first of all. Second, Vista just went through the Vista Capable mess where the basic version of Vista became tainted in market and these chipsets were good enough only for Vista Basic.

If we began selling XP again for Asus, then we would have to offer it for every Netbook. And if we offered it for Netbooks then what would stop OEMs and ultimately customers demanding it for every PC. Suddenly it was looking like a roll back of Vista, especially if we participated. We didn’t really have a choice. Either we would lose the sockets to Linux, the modders would continue to pirate XP and hundreds of thousands of computers would be running a Frankenstein build of XP which already had tons of security problems, or we could suck it up and let the OEMs sell XP.

It turns out Intel was in a bit of the same situation. They were starting to worry that OEMs would want to make many more laptops out of the low power chips and that would take away sales of their more powerful and profitable laptop chips. Intel defined the Netbook category, and thus availability and pricing of low power chips, to require certain maximum screen sizes and configurations. This constrained what would technically be defined as a Netbook. Microsoft used these same definitions, chief among them the tiny screen size, to offer Windows XP. This had a side-effect of extending the Windows XP lifecycle even more. When we finally celebrated the end of Windows XP it was years longer than originally planned entirely due to Netbooks, though the industry would remember this as a story of the failure of Vista in general.

In the Spring of 2008 after what could be dubbed the Asus Eee PC holiday season, Intel announced the name of the chipset to power Netbooks, ATOM®. With that both Intel and Microsoft were all in on Netbooks, and so were all the OEMs. The collective positioning of Netbooks was as a companion to a primary computer, though that was just marketing. Intel called them MID, for mobile internet device, a third category of device that was neither a mobile phone nor a laptop but a highly portable companion computer. A lot of customers genuinely bought Netbooks as their new laptop.

The industry was filled with concerns over margins from these devices. Intel chipsets that cost around $100 for a laptop were half that for a Netbook. At under $400 there was little room for either margin or innovation. The New York Times wrote of these concerns in 2008, “[D]espite their wariness of these slim machines, Dell and Acer, two of the biggest PC manufacturers, are not about to let the upstarts have this market to themselves."1 No OEM was going to be left out of what could potentially be a big shift.

Maintaining low prices, especially around $399, posed some problems, mostly the need to cut back on other components and capacities. Intel dropped many of the required aspects of PCs, such as extensible memory, large disk drives, and DVD drives, in an effort to develop the platform that ASUS and others would follow. The PCs would be like a phone—bare bones with all the components essentially built in with little official extensibility. They would have 10-inch or less screens, presumably because of the category but in practice because small screens were super cheap, and, importantly, Intel did not want to see PCs that might compete with profitable, mainstream 13-inch laptops.

The typical specifications of a Netbook were an ATOM processor, 1 or 2GB memory, Wi-Fi, USB ports, SD card reader, a web camera, and 2GB to 4GB of solid-state storage, as opposed to a spinning disk drive. The screen would be an inexpensive LCD running at 1024x600 resolution, with graphics bumping up against the low-end Vista Capable designation. Windows laptops had not yet incorporated solid state storage at all, which made Netbooks rather novel for techies.

For those keeping track, every single one of those specifications was less than the minimum system specifications for the lowest-end Vista PC. Every. Single. One.

That was the rub. These were low-end PCs in every sense. Some of the specs were borderline awful, most notably the screen resolution of 1024x600 was at the limits of what Windows XP would correctly display. Many interactions with Windows would be tricky with so few pixels and much of the Internet and Windows applications would really struggle. By struggle, it was not uncommon to get into a situation where the button that needed to be clicked was off screen and simply unavailable having run out of display area. At times the display just didn’t show enough rows, or the text was too small to read or edit.

HP, Lenovo, Asus, and others released a flurry of devices all with nearly identify specifications. Even though the devices were identical at the processor and chipset and even power adapter, they differed in keyboards, display, and quality of storage used. These small differences were the full-employment act for tech enthusiast web sites that tracked every development in this hot new category.

Personally, I was really into my Netbook. I was already wedded to the 11” form factor having made a switch to use only super portable PCs anyway. The Netbook was tiny, but the low-end nature of the hardware became an ever-present reminder of the need to make Windows 7 work on much less hardware than Vista did. I ran on a Netbook full time for most of the Windows 7 development cycle. The photo in the previous section of me holding up a Lenovo IdeaPad S10 with “I’m a PC” sticker was my very own Lenovo which I even modded myself to 4GB of RAM and a faster solid-state drive. I managed to blog a few hundred thousand words on the tiny keyboard as well. Where it really came in handy was how I constantly used benchmarks and slow operations to annoy the engineering managers. I loved it, but I was a willing subject.

Behind the scenes thought something else was going on. The reality was that the root of the Netbook was not just OLPC and the next billion PC users, rather it was both Intel and Microsoft or Wintel’s inability to transition to a mobile world. The iPhone that released just before the availability of the Eee PC was built with an ARM chip, which technically is a system-on-a-chip, or SoC. ARM chips were what powered the new generation of devices from portable music players to mobile phones to the new iPhone. A SoC packages much of the whole board of a Netbook into a single chip that specifically includes at least the microprocessor and graphics, small and energy-efficient package. The Intel ATOM line was not quite a SoC, though over time it would evolve to be one, at least in name. What made it possible to run Linux and Windows was the combination of compatibility with Intel instructions and the support for PC-style peripherals such as graphics and storage. Microsoft’s version of Windows for the ARM SoC was Windows Mobile, built on the aged Windows code base.

Intel’s entry, or lack thereof, into mobile computing and building a system-on-a-chip components to power mobile phones contributed to the origin story for ATOM. Intel had substantially invested in an attempt to bring the Intel x86 architecture (or IA, as they called it) to mobile phones. Famously, though, Intel ended up not collaborating with Apple on the iPhone, as CEO Paul Otellini felt Apple’s required price was too low and by some accounts desire for control too high.2 While the initial foray for ATOM was aimed at OLPC, many would claim that Netbooks were simply an effort to make something out of the failed investment for mobile. Since they were fully compatible at the instruction set level with other chipsets, an idea was to build a new laptop—essentially to rescue their failed entry into mobile chipsets. Since these chips drew less battery power, were smaller in size, and less expensive, Intel decided to suggest OEMs create small and inexpensive PCs with them.

In essence, the Netbook arose out of a desire to make use of a low-end chip that originally was meant to compete with ARM and to be used for mobile. While it was compatible with Windows, it was by most accounts inadequate for modern Windows, especially when it came to graphics. The small screen size, while convenient as a demarcation for the Intel chip product line and Windows XP license, was also a necessity because the graphics chipset could not drive a much larger screen.

Nevertheless, Netbooks were flying off the shelves. They were the talk of the industry. Over the next six to 12 months, the sales of these low-end PCs skyrocketed to 40 million units a year—more than 15 percent of all PCs, which was exactly what OEMs loved, especially ASUS that made a big bet. Unfortunately for all involved, the profits were slim across the ecosystem, and worse, the exuberance was truly cannibalizing laptop sales, though not ASUS, which had the new, hot product and a much smaller laptop business. When I visited southeast Asia or Africa, for example, internet cafés had a half dozen netbooks where a single PC once would have been—quantity of endpoints over quality of experience.

Over the course of 2008 leading up to mid-2009, Netbooks remained great sellers. Even if a Netbook was sold with Linux, the demand for Windows was such that pirated Windows XP that was hacked to fit on the available storage became the standard. That seemed to benefit Microsoft in the long run, I suppose. These PCs were seemingly falling from the sky in massive numbers and while the business side was worried about the pricing of Windows and piracy, the product side was happy with something new, finally. There were review websites entirely devoted to the Netbook craze, chronicling the latest developments. In a sense, what was not to love about low-priced computers if people were reasonably happy?

There was little Microsoft could (or should?) do to thwart the momentum, especially because we did not want to lose to Linux. We would have loved nothing more than the likes of HP or Dell to work on Sony VAIO-style PCs that competed with Apple, but that was not to be for a few more years. The PC ecosystem was once again proving that a race to the bottom on pricing and experience was what drove it.

Over time Netbooks expanded in system specifications, OEMs constantly bumping up against the constraints both Intel and Microsoft put in place on what was a legit Netbook. Some added slightly larger screens, making them even slower because extra stress on the under-powered graphics chips. Some added full-size spinning disk drives. Some were able to be upgraded to 4GB of memory. The problem was that under the hood these were still ATOM chips. They were not good PCs. Were they convenient, lightweight, and portable? Yes, but they were slow and had poor graphics. YouTube videos skipped frames and were jittery. Web sites that used Adobe Flash were mostly unusable. Games were too slow. Using Office was marginal at best. Even battery life was limited to three or four hours.

Netbooks, however, played an indisputably positive role in developing Windows 7. They institutionalized a low-end specification that was in-market and broadly deployed. We had to make Windows 7 work reasonably well on them.

Peak Netbook could perhaps have been best described by questions about when Apple would make a Netbook, which Intel would have loved. Such an introduction would have legitimized the category. The mainstream business press just assumed Apple would enter the category because it needed growth, and it was missing out on the hottest new category selling tens of millions of units.

Steve Jobs’s answer to Netbooks, in a uniquely Apple way, was the MacBook Air, which was announced in late January 2008 just after the Eee PC holiday season. Apple’s answer to a $400 Netbook was a $1,799 premium Mac. Classic Apple. The “world’s thinnest notebook,” said Steve Jobs, and Walt Mossberg said it was “impossible to convey in words just how pleasing and surprising this computer feels in the hand.”

It simply wasn’t in Apple’s thinking to release a sub-optimal product. Even the low-priced point products from Apple are fully capable with little compromise. Netbooks violated that core tenet of Apple and so there was no legitimate reason to expect anything other than for Apple to completely ignore this new category the way the industry defined it.

In April 2009, Tim Cook even took to their earnings call to trash talk Netbooks:

When I look at netbooks, I see cramped keyboards, terrible software, junky hardware, very small screens. It’s just not a good consumer experience and not something we would put the Mac brand on. It’s a segment we would not choose to play in. If we find a way to deliver an innovative product that really makes a contribution, we’ll do that. We have some interesting ideas.3

At least through 2009, the MacBook Air remained Apple’s answer to small, portable, and even low-priced computing.

There were, however, enough criticisms of the initial MacBook Air to allow PC makers to look the other way or actively market against it by pointing out the lack of ports and extensibility. Instead, the race to the bottom with Netbooks continued. OEMs and Intel would stick with this approach for several years, while Apple refined its new approach to making laptops, eventually even bringing the price down on the MacBook Air. The result was rather crushing. PC elites quickly started running Windows on MacBook Air hardware simply because the hardware was so good, and Apple even provided instructions for how to do that. I can’t even count the number of meetings with OEMs, email threads around Microsoft, and queries from the press I received, asking, “When will there be Windows PCs like the MacBook Air?”

The ecosystem stuck its collective head in the sand all while we rode Netbooks up and then, in a short time, straight back down. In hindsight, the Netbook runup hid the secular decline in PCs that had begun with the recession following the Global Financial Crisis. It would take years to recognize that, and a massive effort for the ecosystem, and Microsoft, to respond to the ever-improving MacBook Air.

Understanding and somehow addressing the relentless force driving the PC ecosystem to produce what most tech enthusiasts see as lesser quality devices (especially relative to Apple) remained one of our key challenges. Too many saw the rise of Netbooks as the answer to products from Apple while not being able or willing to respond directly. There was a fundamental difference between the volume platform appealing to the “masses” and the premium platform appealing to a smaller and more “well-off” segment of the market. That mental model held until the iPhone and MacBook Air. We had reached a tipping point.

With the iPhone, App Store, and MacBook Air Apple was not simply on a roll but the biggest roll of all time from 2006 through 2008.

At the same time, we were deep into building Windows 7 and starting to feel good about the progress. It was time to get out and share our optimism.

On to 094. First Public Windows 7 Demo

“Smaller PCs Cause Worry for Industry”, New York Times (Online), Jul 21, 2008

“Paul Otellini's Intel: Can the Company That Built the Future Survive It?”, The Atlantic May 2013

Apple earnings call transcript from April 2009.