083. Living the Odd-Even Curse [Ch. XII]

“Sinofsky to the Rescue! … (?)” — blogger Who da’Punk aka Mini-Microsoft

Welcome to Chapter XII, where Hardcore Software turns from Office and enterprise customers to Windows and consumers (and PC makers). For many readers, this will also be a bit more of their own lived experience. As such it is worth a reminder that I am sharing my experience and observations, not any sort of omniscient history (if such a thing even existed). Importantly, by waiting a decade to write, the history becomes much clearer and less influenced by the emotions or immediate reactions. That’s certainly been my experience so far in writing HCSW. These next four chapters (about 25 sections) will cover Windows 7 and Windows 8, with a decidedly different approach than the previous 11 chapters. We will see much more focus on organization, strategy, culture, real competition and disruption, and the challenges and opportunities seen in a big giant company.

Back to 082. Defying Conventional Wisdom to Finish Office

2006: The year was marked by cultural shifts. BillG announced he would step down as chief software architect, a transition that would take two years. I was given a new role and faced multiple corporate and culture challenges, and outside of Microsoft the tech landscape was changing too. And fast. “To google” was added to the dictionary.

By the start of March 2006 the Longhorn product cycle had been a chaotic five-plus years that included the security work for Windows XP, the release of Windows Tablet PC, Windows Media Center, Windows 64-bit, Server releases, and importantly, a major project change called the Longhorn Reset, essentially defining a new scaled-back product mid-flight based on the original Longhorn. The Windows team had been through a lot and was not finished. Longhorn had been receiving a lukewarm reception from users of a big Community Technology Preview release since the fall of 2005. The team, however, had started updating the product more frequently and momentum was indeed shifting by early 2006.

Windows Vista, as it was officially named, was still an unpredictable amount of time away from shipping. While not public at the time, a couple of weeks down the road, Microsoft would announce a final and just-decided delay to ship Vista for availability in January 2007. The team could not commit to making the release available in time for PCs to be sold for back-to-school or holidays 2006. Vista would eventually release to manufacturing in November.

Windows was still on fire with PC sales breaking through 200 million units in a single year for the first time, demonstrating extreme product-market fit. Both Servers and Tools were doing well, extremely well, except there was a nagging problem emerging from across Lake Washington called AWS, Amazon Web Services, a shift from companies buying Windows to run on their own server computers to renting storage and compute in the (or a) cloud. There was a good deal of tension between Windows team and the Server team. The Server org required the Windows org to contribute to shipping a new Server. This delayed a new Server product, slowing their release based on Longhorn until the next Windows release. The .NET framework and Visual Studio had become leaders for IT development within corporations, but the onslaught of Linux, Apache, MySQL, and PHP (later Perl/Python) continued to dominate the public internet and the university programs in computer science.

On the RedWest campus the investments in online services faced a myriad of revenue, cost, product, and usage problems that were not nearly as visible as the Windows challenges. Wall Street, however, was growing increasingly impatient with financial results, which seemed to punish SteveB for his transparency. There were dozens of Microsoft online services, some branded as MSN and others using a new umbrella name Windows Live, in every conceivable category from selling cars (MSN CarPoint) to chat (MSN Messenger) to finding Wi-Fi hotspots (MSN Wi-Fi Hotspots.) Microsoft seemed to be searching for a big win against Yahoo and a rapidly dominant Google in the world of internet advertising and consumer services.

Google was top of mind for many, not because so many groups across Microsoft competed with Google products but because of the aura the 2006 Google culture achieved. Google was fast. They were innovative. They were empowering. They had “20 percent time” when engineers could work on whatever they wanted one day a week. They had free gourmet food and a chef, all day long, compared to our grungy filtered water dispensers and subsidized airport food with limited availability. They had snacks and we still had noodles and one type of V8®. They had massages, while we had a multi-purpose sports field, but no towels (note, towels returned in the summer 2006.) We had individual offices and they had collaborative open plan cubicles (you read that correctly, Microsofties complained about having offices.) They had a modern, flat organization with 50 reports to a manager (yes you read that right too.) In the blink of an eye to me, everything we held near and dear and made Microsoft an icon of business culture, seemed to be old, tired, and either wrong or inadequate, like wearing khakis, loafers, and a button down to Burning Man.

Google Chrome was still almost three years from launching while Internet Explorer had 90% share. The last new release, however, was Internet Explorer 6.0 launched five years ago with Windows XP frustrating users, web developers, and the market. Gmail was about to turn two and it was crushing Microsoft Hotmail with its superior junk mail filter and massive free storage. Microsoft just started to build its own web search product which would launch in 2006 as Windows Live Search into a market where Google had already overtaken Yahoo and grown to half the market while gaining a half point of share every month.

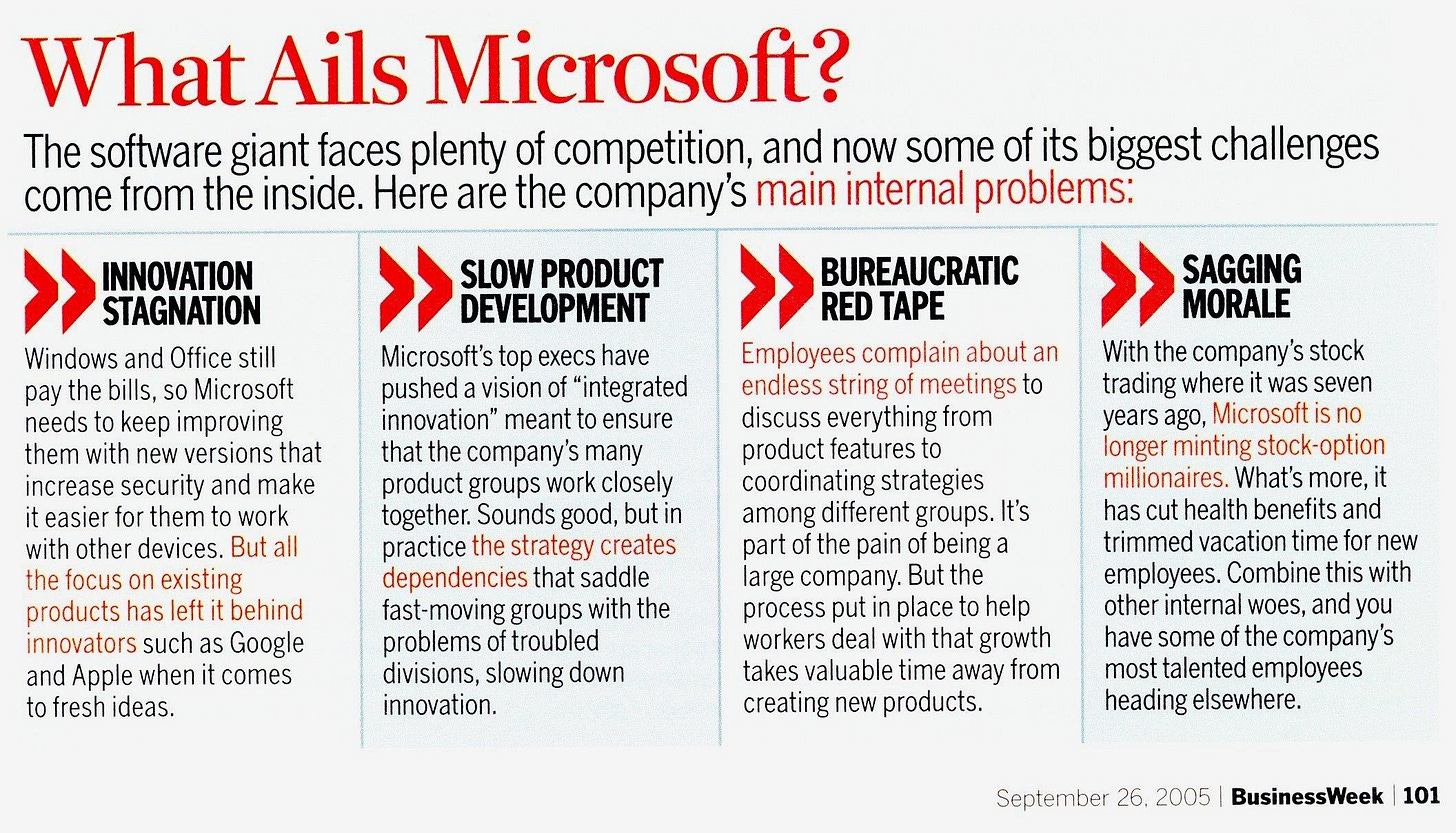

As Vista was creeping along, albeit faster these days, toward shipping, there was a much deeper problem in Windows that was symptomatic of the broader malaise or even open hostility across the company, especially in engineering. Even though the company kept putting up blockbuster numbers, the morale across product groups had declined. Vista had contributed to that. Integrated Innovation had as well. Integrated Innovation was the expression at the CEO level of the desire and right to build integrated software, which continued to be challenged in the courts and among regulators. Internally, this was the opposite of what people wanted to hear because the feeling was Integrated Innovation, or synergy, was what had first gummed up Microsoft relative to Google. The yearly Microsoft Poll survey was a litany of complaints and issues from employees across most of the product groups.

In a semantic twist, the phrase was later morphed into Innovate then Integrate. That might not have helped. In reality the pressure for synergy had not relaxed at all as it was a cornerstone of Microsoft’s (and BillG’s) strategy and culture, even more so as the company became an enterprise company given how much enterprise customers and the enterprise ecosystem valued synergistic strategy, or maybe strategic synergy. Strategy was the anchor holding back Longhorn. A scathing cover story in the September 26, 2005, BusinessWeek, “Troubling Exits at Microsoft” painted a picture of employees departing, malaise, and the rise of Google. Even a longtime member of Microsoft Research’s Technical Advisory Board, Carnegie Mellon professor Raj Reddy, called for a company breakup to support more “nimble operations.”

But the biggest problem was that we felt like we were losing, and Wall Street felt that way too and the stock price reflected that lack of enthusiasm.

We were losing to Google. We were losing to Yahoo. We were losing to BlackBerry and Nokia. We were losing to Sony. We were losing to Oracle. We were losing to SAP. We didn’t have anything to compete with AWS. We were losing to Apple when it came to PC hardware. We had already lost to Apple’s iPod.

In the years ahead, we will see accelerating change in the software industry, as the computing needs of our customers start to move beyond the PC into a “PC-Plus” world. The PC will undoubtedly remain at the heart of computing at home, work, and school, but it will be joined by numerous new intelligent devices and appliances, from handheld computers and auto PCs to Internet-enabled cellular phones. More software will be delivered over the Internet, and the boundary between online services and software products will blur. The Internet will continue to change everything by offering a level of connectivity that was unimaginable only a few years ago — and every home, business, and school will want to be hooked up to that incredible global database. —Annual Report, 1999

Our competition with Apple was becoming increasingly sharp compared to past years where our view was essentially to ignore them, going way back to the launch of Windows 95 and the “C:\ONGRTLNS.W95” full page advertisement in The Wall Street Journal. In 1999, BillG wrote an oped for Newsweek and a month later proclaimed in the 1999 Annual Report to Shareholders1 2 that the “PC-Plus” era was upon us. With this Bill was describing an era where PCs would continue to be central, but rather than part of every scenario they would be surrounded by devices that connect to a Windows PC.

This framing of the future became more visible and widely used across Microsoft communications as the temperature of the competition from all corners heated up.

The PC-Plus era is rooted in a response to what had been simmering among the tech press from as early as 1993 when Walt Mossberg first used the phrase “Post PC.” The first wave of connected devices began with the EO Communicator in early 1993 and then the Apple Newton available a bit later. In his review of the EO, Mossberg described the device as not “the kind of post-PC device that promoters of the PDA concept have promised: something with the price, size and battery life of a Sharp Wizard, but the smarts and communications ability of a good PC and an advanced phone.” Whereas in the review of the Newton he described it as “a post-PC device that streamlines data entry, links all of your information in intelligent ways and adapts to your handwriting and work habits over time.”

A few years later with the 1999 arrival of the Palm VII, the first truly connected and mobile-phone sized device, the punditry was running full throttle declaring the arrival of the Post PC era. The trade press was filled with editorial and widespread usage of the term, much to our dismay at Microsoft.

Bill Gates, Paul Otellini, and others in the PC industry went on a bit of a campaign defending the PC and declaring the PC-Plus era. They executed a series of OpEd pieces and other marketing efforts to thwart the notion that the PC was dead. In The Wall Street Journal in May 2006, just after I started working on Windows, they wrote an OpEd explaining why and how the PC will continue to thrive.3

So, the next time you read about the end of the PC era, think about what you do when you get home from vacation and want to share the pictures on your digital camera with family and friends. Or where you go to download music and videos onto your iPod or MP3 player. Or how you synchronize the contacts, calendars and email on your handheld wireless devices. Or where you go when you want to find new music or search for that episode of "Lost" you missed last week.

You sit down at your PC, of course.

As this shows, the defensiveness around the PC became increasingly obvious and the technical justifications increasingly detached from where the industry was heading.

There was no shortage of problems on the Windows front, in contrast to Office which seemed on both solid footing and heading calmly to a new era. Despite the chaos, upheaval, corporate strife, and my own apprehension, I was about to run towards the fire.

Office Hours

I was sitting in the guest chair in SteveB’s office while he was standing, swinging his golf club. He stopped, finally, and said, “Thank you. Thank you.”

With great enthusiasm, those were his words as he shook my hand with all the vigor of a salesman closing a deal. A handshake between product group Microsofties was so unconventional that it added to my uneasy feeling.

Uncertain as I was, I accepted the role of leading Windows product development.

But it would not be so simple. That also meant managing the struggling Hotmail, the new Live Search, and the loved and popular, though shrinking MSN Messenger, along with several other online services. I would report to Kevin Johnson (KevinJo), who had joined Microsoft from IBM in the early 1990s and risen up the ranks by building out the company’s customer support arm and then to running the worldwide field organization (after Microsoft he went on to become the CEO of Juniper Networks and then Starbucks). Kevin would provide much needed stability across his enormous portfolio, which included all of Windows and Server, Tools, Servers, and online services. The big news was that Kevin was taking on a new and huge product development role, essentially everything except Office. The way I thought about Kevin’s job was he was on the hook to lead competing with Apple, Linux, Google, Yahoo, now Amazon, and the rest of the internet. The key thing for me was that one person oversaw every major customer segment at the company: consumers, PC makers (Microsoft’s largest source of revenue concentrated in about ten customers), developers (developers, developers), small business, enterprise IT, and now advertisers. It was kind of nuts for one person to be asked to manage all of that I thought. My job was to help him by making sure Windows was taken care of.

The Windows team had been divided into two big teams for quite some time. The core operating system was known as Core OS Division, COSD (pronounced “kahz-dee”). COSD led the parade at creating Windows, drove the engineering process and culture, and was staffed with first among equals. COSD owned the operating system kernel, device drivers, file system, networking, security, and in general the guts of Windows. The team was where the original Windows NT architects all worked. When Jim Allchin (JimAll) created the COSD organization he and I spoke about how we built the Office team (the original Office Product Unit a decade earlier) and COSD was somewhat mirrored after that, at least they thought so. About half the Windows resources were in COSD.

The other half of Windows was known as Windows Client and embodied the user side of Windows including the graphical interface, the explorer, start menu, control panel, printing, faxing, and all the experiences from tablets to media playback, to Windows Media Center, and importantly Internet Explorer. What COSD was to process and hardcore, Client was to “doing cool stuff.” A visit over to one of the Client buildings and you were likely to see displays of cool new media players, fancy gaming PCs, or the latest in wireless gadgets. There was always a cool demo to be had. Showing off COSD innovation was a lot more tricky.

There always seemed to be tension between COSD and Client. Whether it was about the schedule, testing, or different views of the engineering process. There was not a lot of love lost between them. This might seem weird to many. To outsiders, I am positive the early days of the Office Product Unit tension with Excel and Word would look identical.

For clarity, the Windows Server product worked closely with COSD but owned the product definition and the unique components differentiating Server from regular desktop Windows. Yes, it was a complex matrix.

Technically I was to manage Client. COSD was driving the Longhorn project even though Client was 100% engaged on that. No need to upset anyone with a new boss anyway. We would figure out the details of COSD at some future date closer to when Longhorn would ship. I also took on half of the Windows Live Services, which were also divided into two orgs as well (front end and back end.)

If this sounds a bit halfway, that would be a valid observation. It was certainly confusing to outsiders searching for the new boss of Windows, which JimAll was previously. In total fairness, very large reorgs are never finished before they start to roll out. There is always a balance between completeness and fighting the inevitable leaks that prove even more distracting. The press release from Microsoft tried to detail the organization but from the outset it was complex.

Was I up to this job? Was the team up to me in this job? Could a person with experience only in “boxed” software work in the modern world of online services? An Office guy running (half of) Windows? That seemed like a punchline to a bad reorg joke.

And what did we need to accomplish? Tackling the challenges faced by Windows seemed, well, perhaps too late to the party. They still hadn’t finished Vista after the Longhorn reset and it wasn’t clear when it would ship. Did I have to ship Vista first? What if Vista turned out fine and customers were happy? Or did Windows need to be reinvented? Brought back to life? Or both? And, if so, what level of urgency was even possible? What did the individuals on the team think were the problems?

I had never hemmed and hawed about a job change or negotiated any titles, terms, or conditions, and I didn’t for this one—just two weeks going back and forth, mostly with BillG to get a sense for his candid thoughts. My new role marked his last staffing efforts with SteveB—the last “Bill person” to move into the Windows job. Though I was not ever going to be a “Steve person” because of my lack of field experience, we both worked equally hard to see each other’s perspectives.

All the best choices I had ever made in life were counter to my exceedingly planful product execution, without strategizing, lists of pros and cons, or excessive deliberation. I just went for it. I was lucky in that regard having not really made a poor choice, yet.

But I was tired. I had been going nonstop since graduating 1987 and had, for all practical purposes, given my 20s and 30s to Microsoft. Was I about to turn over my 40s?

This opportunity was sure to be all consuming.

A management transition for Windows was a material corporate governance event, and thus a formal announcement needed to happen quickly to avoid the potential of leaks to Wall Street. Plus, there were many anxious people across the company who had both a need to know what was going on with Windows, and a need to influence what was going on (or believed those to be the case).

“Quickly” turned out to be an understatement.

The Vista team sent out a team-wide mail as well as communication to partners with an absolute RTM date of October 25, 2006, a slip from the previous August target. This was essentially external communication and would generate press. However, word already leaked to The Wall Street Journal about me moving over to Windows. The PR team began negotiating by trading verification of facts in an effort to delay the story. The story was going to run on March 22, 2006.

The clock was ticking to actually get an announcement done. The announcement scheduled for the morning of Thursday the 24th would not be moved even with the WSJ story.

Within minutes of accepting the job, I was informed that my first meeting was to be held immediately to go over the announcement tick-tock, an expression I had not seen used before inside Microsoft. I was also asked for my internal comms contact, my external comms contact, my human resources contact, my executive assistant, and my chief of staff. Time was short. There were almost 40 people on a mail thread summarizing the process.

I had no staff, so I replied, “Just ask me.” I suspect everyone on the mail thread had no idea what to do with my response, but it sure cut down on the email traffic as there was a bit of a culture of fear in Windows when it came to sending mail to an executive, especially a new boss and one they had not worked with.

I forwarded the mail to our executive assistant leader Collen Johnson (CollJ) and then immediately walked into her office. I shook my head as if to ask, “What did we get ourselves into?” I knew Colleen was already buffering a huge amount of noise, mostly people asking if I really meant for them to ask me directly.

I arrived at a conference room in building 34, the big executive building, to a room of what appeared to be a re-org war room. There were easily 30 people, standing room only, more people than I think I’d seen in a meeting since we signed off on Office 2003, all to plan the announcement of my new role. The big conference table was covered with handouts of org charts, talking points, and draft press releases and rude Q&A docs. I didn’t know most of the attendees. It was funny because this was not a restructuring or anything complex; it was news of a retiring executive JimAll, a new executive boss, Kevin Johnson, and then me. It seemed that every vice president involved in this announcement sent two or three people to the meeting but didn’t show up themselves. Questions quickly started mounting over messaging, email cascades, and heads up. The production values well exceeded the actual announcement being planned.

As much as I understood the importance of this announcement to the business world and to the team—after all, this was the retirement of legendary technologist and leader Jim Allchin and a material event for a public company—the craziness (and that’s what this was) around a single announcement represented a microcosm of the entire situation. I was no longer in the comfortable garden MikeMap had created for Office.

With a lot of effort, the room managed to get the information that everyone wanted to go into this announcement down into a single email response to the official press release and filing, which I wrote, which came from me, and had one small set of talking points for any press calls that PR would handle. There was to be no email cascade—a new word for me that meant a process where an email went out from the top to the organization, and then every level of management forwarded that email (that people had already received) to the team(s) they managed with their own words interpreting the org change for them. Since there were parts of the Windows team that were nine or even 10 levels deep, the amount of interpretation that went into these cascades was mind-boggling in the depth and breadth of potential misinterpretation.

Turns out, we needed none of that with this announcement. Why? There would be no outreach or interviews by anyone at this stage. Most of all, literally nothing would change until Vista shipped.

That was the only talking point that mattered.

I was not joining Windows with some sort of secret master plan nor did we want the announcement of my job to portray me as some sort of Vista savior. Still, it played out a little bit like that in the press. There was an uncomfortable 36 hours between that WSJ story and the official announcement. That’s what happens when things leak.

The Wall Street Journal said, “[Sinofsky] has a reputation as a meticulous manager who is adept at controlling large software projects.” Paying homage to MikeMap, the article said the Office team culture was created by “an executive recruited from International Business Machines Corp., the Office group adopted a more management-heavy, disciplined culture . . .” The headline read, “Microsoft delays Windows Vista debut again; consumer version to miss critical holiday season; unit shake-up is expected.”4

The rest of the week saw much of the press derived from the WSJ and the announcement focused on my new role in fixing Windows. There was no way to avoid this. It was broken. I guess it was also the truth. Business 2.0 ran with a headline “The Man Who Could Fix Windows: Microsoft's new OS chief has to get Redmond to embrace a new model of programming, in which software is constantly being improved instead of updated every 5 years.”5

Inside the tech industry, one of my longtime favorite foils in the press, Mary Jo Foley of ZDNet, said, “Sinofsky has the reputation of a strict, schedule-bound manager who keeps the trains running on time.” After all these years, and quite a bit of product innovation from the team, I was basically a strict project taskmaster. That stung, in a Spock-like way. But later the ZDNet editorial team added more, “The Sinofsky promotion (not sure we’d consider being named Windows Mr. Fix-It constitutes an upward career move) grabbed the most headlines.”

And finally, everyone’s favorite anonymous internet whistleblower, Mini-Microsoft, a widely read blog maintained by anonymous author calling themself Who da’Punk offered thoughts. To clarify the record once and for all, I was not the writer and have no idea who was though at least two reporters met the blogger in person verifying that fact. The post on March 23 had a headline that read:

“Sinofsky to the Rescue!. . . (?)”

The article said, “There’s a new sheriff in town, and he’s aimin’ to gun down any rootin’, tootin’ varmi[n]t that can’t deliver what he committed to. Maybe.”6

It is probably important to detail Mini-Microsoft at this time because they were a fixture over everything that was going on at Microsoft, even if I chose to ignore them the rest of the Windows team and the company followed every word (and so did the press). Mini, as in “Did you see the latest Mini?” or “Well, that really pissed off Mini” wrote about all topics Microsoft though seemed especially focused on the plight of typical employees struggling to make sense of what was going on. Mini was especially critical of typical big company problems such as organizational bloat, excess hiring, lack of innovation, performance reviews, promotions, salary, and more. Mini was also critical of our technical strategy and challenges around Longhorn. Like many claiming informal whistleblower status, the challenge was always there for an executive to respond to critiques, but it was so difficult to do so knowing Mini did not always have the complete context.

It is difficult to parse today but when reading Mini’s posts one of the most interesting aspects is how they turn the phrases of Microsoft’s HR and leadership back on them. From accountability to synergy to integrated innovation and even “I love this company” which was classic SteveB. Beyond that I proved to be a subject, directly or not, over the next couple of years in many of his (eventually their gender was identified in the press) over 100 posts. Mini even got himself a profile in BusinessWeek, as part of the much larger negative story about the loss of talent at the company.

I had no real direct reports at this point because everyone, including BillG, was finishing Vista. Still, I needed a way to quickly connect with a large number of people in a way that felt more . . . intimate.

To move forward, I chose a decidedly non-traditional path. The Microsoft way might have been a big all-hands meeting, a follow-up email with vague statements of support, or an immediate gathering of a staff meeting. Instead, given the need to both ship Vista and meet a lot of people I looked for a way to communicate broadly while connecting in-person with many, all while not getting in the way at all of Vista. This meant, for example, turning down all the escalations or crisis moments that people would bring to me. For example, in July AMD announced the intent to acquire ATI, the graphics card makers, which caused a brief panic in how to handle shipping ATI drivers in Vista. Given the future impact of this choice many tried to pull me into this crisis. This was a brilliant acquisition and noteworthy that Intel did not lead or follow up with acquiring then similarly-sized Nvidia.

I browsed over to the internal SharePoint site and created a new blog called Office Hours in an effort to signify openness and a risk-free place where ideas could be shared. Blogging the goings-on proved to be the best way to reach a team of approximately 10,000 people and, as I would learn, the rest of the company.

Over the course of six-and-a-half years, I wrote more than 400 posts amounting to nearly three quarters of a million words (1,700 pages), answering questions, discussing the how and why of all we were doing, not doing, or considering, and detailing almost every aspect of the business. I wrote something substantial most every week, sometimes twice. Posts covered product strategy, organization structures, people management, competition, features, culture, my personal management, and just about everything in between. I posted the trip reports I dutifully wrote after conferences, recruiting trips, and customer visits. Many of these posts were included in a book I co-authored with Marco Iansiti of Harvard Business School, One Strategy: Organization, Planning, and Decision Making (Wiley, 2009.)

I had one last meeting with the Office team. We gathered the Senior Managers, the most senior 120 or so people (the dev/test/pm triads as well as general management and discipline leaders across design, planning, localization, content, operations), in the big conference room where I shared the news that was about to break. Even to this day it was the most emotional day of my years at Microsoft. I looked out over the room and saw people I had all but grown up with professionally, many of whom I’d known for my entire time at Microsoft. Mostly I sensed they were worried about me—the look on their faces said no one goes over to Windows and lives to tell about it.

As I was packing up my office to move across the street to a temporary office in Building 50, a member of the team stopped by and delivered the most wonderful hand-made lightbox of Office logos and packaging over the past dozen years. It still sits on my shelf with the signed note. It means the world.

This was just my first couple of days. Even though for the time-being I had no direct reports, I still needed to figure out who and what would eventually be on my team. The team was incredibly anxious and clearly expected both a master plan and a reorg. I realized that many people had observed or become a fast study in how the Office team worked. Many were prepared with arguments as to why the way Office worked (at least their perception of that) would never work in Windows.

I had a sneaking suspicion that SteveB and BillG wanted a quicker “fix” than I might deliver. Even though I had not only lived the Windows challenges for at least a decade and many of the people were well-known to me through countless meetings, offsites, email exchanges, and more, the one thing that is certain is that talking about fixing something is a lot easier that actually fixing something.

On to 084. Who’s On the Team, Exactly?

Newsweek, May 31, 1999, “Microsoft’s New Office”

Microsoft Annual Report, June 1999. https://www.microsoft.com/investor/reports/ar99/download.htm

End of the PC Era? Hardly! by Bill Gates and Paul Otellini, 15 May 2006, The Wall Street Journal

Wall Street Journal. Guth, R. A. (2006, Mar 22). Microsoft delays windows vista debut again; consumer version to miss critical holiday season; unit shake-up is expected.

https://money.cnn.com/2006/03/24/technology/business2_msftreorg/index.htm

http://minimsft.blogspot.com/2006/03/sinofsky-to-rescue.html

So excited about this upcoming section! I joined cosd in '06 out of grad school. First jobs leave deep impressions. Your framing, vision, and planning memos, 3-milestone dev cycles, etc informed how I've thought about large scale software (and hardware) development later in my career.