233. "The Illusion of Thinking" — Thoughts on This Important Paper

This is a fantastic paper. I just love it. tl;dr AI is not human. Anthropomorphization has been bad for AI, LLMs, and Chat. Clippy walked so today's AI could run.

The Paper and Its Premise

At a technical level, the paper asks important questions and answers them in super interesting ways.

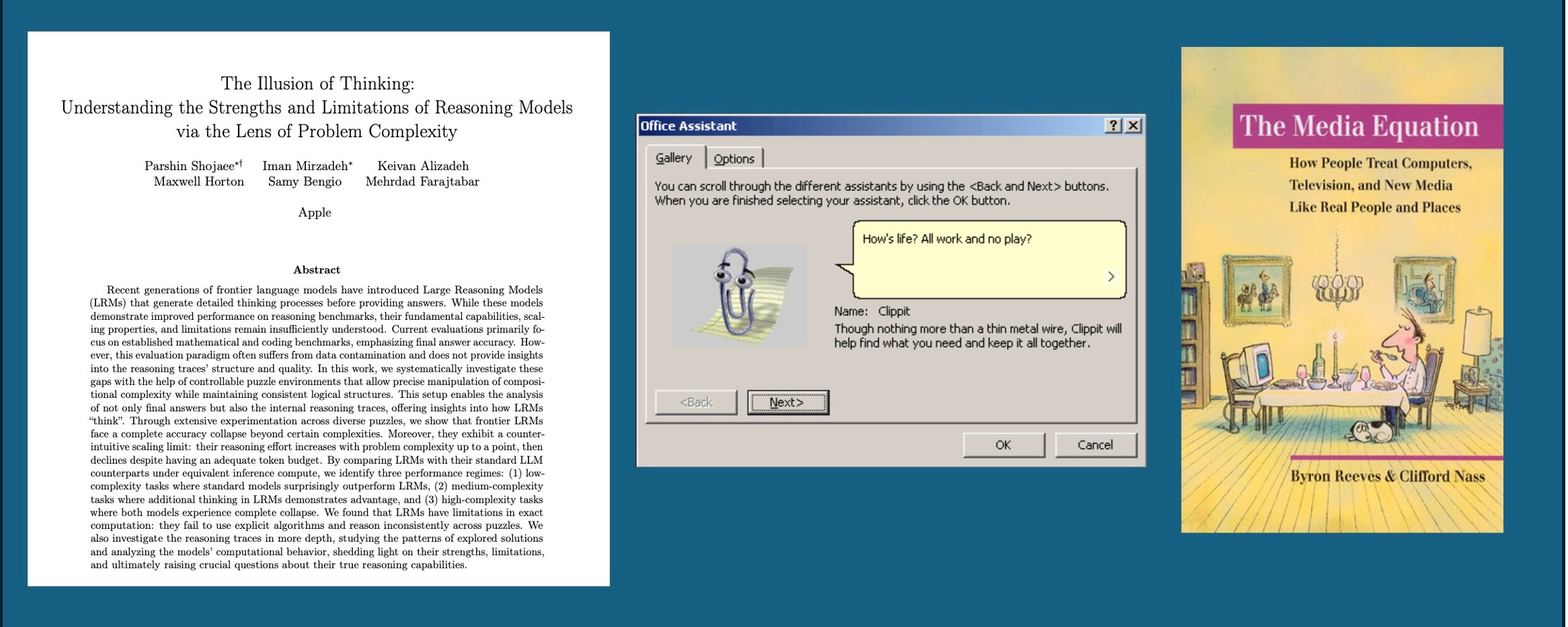

The paper was written by Apple researchers including an intern, The Illusion of Thinking: Understanding the Strengths and Limitations of Reasoning Models via the Lens of Problem Complexity by Parshin Shojaee†, Iman Mirzadeh, Keivan Alizadeh, Maxwell Horton, Samy Bengio, Mehrdad Farajtabar († was an intern). Full link to paper here: https://machinelearning.apple.com/research/illusion-of-thinking

I couldn’t help but walk away with the conclusion that the big problem is not what LLMs do, but the incredible “hubris” that has characterized the AI segment of computer science since its very beginnings.

Addendum: Many AI Doomers—they do not call themselves that—have latched on to this paper as proof of what they have been saying all along. While technically true, their primary concerns were not that models do not think or reason but that models can autonomously destroy the human race. There’s a big difference. The Doomers should not look to this paper to support their hyperbolic concerns.

The Origins of AI’s Human Metaphors

While the earliest visions of computers in applications (going back to Memex even) were about “vast electronic brains,” the AI field was born with the pioneering work on “neural networks.” At first, this was about simulating the brain—which is where the term “artificial intelligence” even comes from. In many ways, there was a naive innocence to this, both in terms of computing and neuroscience. It was the 1950s, after all. See Dartmouth Workshop.

But then, through five decades of false promises and failed efforts—called “AI winters”—innovators chose to communicate their work by anthropomorphizing AI. After neural networks, we had the earliest chatbot with Eliza. Robotics focused on “planning.” Then came “natural language.” The first efforts at “computer vision” followed. One of my favorites was “expert systems,” which tried to convince us we could simply “encode the knowledge of humans” into a linear programming system and do everything from curing cancer to analyzing company sales data.

Machine Learning Rises, and Expectations Follow

As neural networks rose again in the 2010s—and with the work Google did prior to that on everything from photos to maps—the phrase “machine learning” became popular. The idea encoded in that term was that machines were learning. Yes, in a sense, they were learning—but not in any human sense.

The reason for the AI winters was that expectations raced far ahead of reality. While many concepts remained and went on to either make it into products or continue as building blocks, the massive letdown and disappointment were not forgotten. Many people were down on AI, and a big reason was that the field seemed so full of itself all along.

For sure, other fields in computer science were like that too. Object-oriented programming was a massive failure in terms of delivering a quantum leap in programming. Social interfaces failed in terms of usability. The “semantic web” came and went. “Parallel computing” never really worked. Much to the dismay of my department head, programs were never proven or formally verified. And so on.

Anthropomorphizing LLMs: The New Wave

The failures of AI were so epic that people ran from studying it, grants disappeared, and few departments even taught it—certainly not as a required subject. The few who persevered were on the fringes. And we’re thankful for that, of course!

With LLMs and chatbots, the anthropomorphizing really took off. Models learned; they researched; they understood; they perceived; they were unsupervised. Soon, everyone realized models “hallucinated.” We used to say “the computer was wrong” when it offered a bogus spelling suggestion or a search produced a weird result, but suddenly, using AI meant the result was equivalent to “perceiving something not present”—but it’s software; it didn’t perceive anything. It just returned a bogus result.

With Agents, they were going to act without any human interaction. Even using terms like “bias” or “chooses” are highly human traits (think of all the human studies that can’t even agree on what bias means in practice), and yet these terms were applied to LLMs. Most recently, we’ve seen talk about LLMs as liars or as “plotting their own survival,” like the M-5.

And of course, the ultimate—artificial general intelligence. AI would not only be human but would surpass being human.

The Absurdity of Humanizing Tools

Just this weekend, one company with an LLM advocated for a new “constitutional right” (my words), which would guarantee model-user “privilege” like what we have with mental health professionals or lawyers.

The absurdity of thinking we would humanize a digital tool this way—when we don’t even have privilege with a word processor we can use to type our deepest thoughts—is awkward, to say the least.

I would love to have more privacy and have advocated for it, but in no universe is what I say to an LLM more important or even different than any other digital tool.

A Reminder: These Are Tools, Not Beings

Along the way, there were skeptics, but they sounded like Luddites in the face of some insanely cool technology and new products.

Let me say that again—the technology and products are generational in how cool they are. They are transformative. This is all happening. The next big thing is here. We don’t know how it evolves or where it goes. It is like the internet in 1994. But it is like 1994. Many have raced ahead. It is going to take time.

In the meantime, anthropomorphizing AI needs to stop. It is hurting progress. It is confusing people. It is causing stress. It isn’t real.

The Costs of Anthropomorphizing AI

The use of this anthropomorphizing terminology has had three important effects, not all good:

It attracted massive interest.

AI was finally here. AI was always a decade out. Now it works. By using human terms, it was easy for people to imagine what Chat/LLMs did—but without actually seeing them in action, or only seeing what was shown in quick clips, posts, or pods.It created a false regulatory urgency.

Anthropomorphized AI implies it needs to be controlled like humans—with laws and regulations. Worse, the assumption was it would be the worst elements of humans, plus it was faster, smarter, and relentless. The AI Safety movement was born out of easily expressed concerns based on anthropomorphized AI. If AI was smart and biased, or AGI and autonomous, then it must be controlled. Nothing poses a higher risk to our technological future than applying the precautionary principle too broadly to AI.It inflated expectations.

We are right back to where we’ve been with all the previous AI winters—with a risk that everything unravels because of the mismatch between expectations and reality. That mismatch is the root of customer dissatisfaction.

We’ve Been Here Before

There is a well-known dynamic that has been part of computing from the very start: when humans interact with computers, they tend to believe what the computer says. This has been validated in many blinded tests, particularly research done at Stanford in the 1990s.

This was first noticed in the earliest interactions with Eliza. It was well-known through the 1980s that whenever your credit card bill or bank balance was wrong, the default was to blame the computer—and then assume you missed something.

The research was well-documented in the book The Media Equation: How People Treat Computers, Television, and New Media Like Real People and Places by Byron Reeves and Clifford Nash in 1996. I strongly suggest reading this. It had a real influence on how we approached building Office, including all the “agentic” features like AutoCorrect and, of course, Clippy and its natural language interface called Answer Wizard.

Thinking computers are right is, of course, dangerous—but it is human nature to defer to perceived expertise.

Lessons from Clippy: Humility in Design

We learned a lot of lessons building good old Microsoft Clippy. Among them was to be humble. The reason for the happy paperclip was precisely because we knew Clippy was not perfect. We knew that we needed a way to convince people notto believe everything it suggested.

Of course, we were right about that—just wrong about how infrequently we would be correct, given 4MB of RAM, 40MB of hard drive space, and no network. Tons more here in Clippy, The F*cking Clown if you’re interested.

AI Is a Tool—And That’s a Good Thing

AI is wonderful. It is absolutely a huge deal. But it is, today and for any foreseeable future, a tool. It is a tool under the control of humans. It is a tool used by humans. It is a tool, and not a human. The fact that it appears to imitate some aspects of humans does not give it those human traits.

For those reasons and more, we should not be concerned or afraid of AI beyond the concerns over how tools can be used, misused, or abused. That could be said of VisiCalc on an Apple ][, Word on Windows, Netscape and the internet, or more.

Final Thought: Tools, Not Minds

The humans are in charge.

AI isn’t human.

AI isn’t thinking.

It’s amplifying, assisting, abstracting, and more.

Just like tools have always done.

So glad someone finally said the quiet part out loud. It's as if no one read "full consciousness is all you need"...oh wait...my sources are telling me that it's actually "attention is all you need"

I get the reason why people gravitate to making machines appear more natural (and software mimic the real world). But it gets old really quickly!

I think robots will take this to an extreme for a while, until people realize that it's better to have a strangely shapes machine that works super well instead of a human (or cat or dog) looking one that trips, falls and bumps into stuff!