044. Our First Big M&A Deal (Beating Netscape)

We can announce a partnership, something bigger, or even the “full meal deal.” –Chris Peters to the founders of Vermeer, 1995.

Office had been early and aggressive inserting Internet technologies across the product, including hyperlinks (so new!) and HTML, as well, sort of, email with Outlook. We started to notice a challenge for us—web sites were not single documents but collections of documents. Office was not particularly useful for dealing with collections of documents (except for the failed Binder experiment).

We were about to enter the fray, going head-to-head with Netscape to acquire a “hot” internet product being developed in Boston.

Back to 043. DIM Outlook

We enjoyed a very fancy and atypical dinner at Daniel's Broiler on Lake Union. Chris Peters and I were hosting the co-founders of a Cambridge, Massachusetts startup, Vermeer Technologies, Incorporated. It was awkward. Only after would we learn that none of us knew what we were doing and we were all nervous and kind of terrified.

If email was the biggest application on the internet, the technology that was causing Office the most strategic concern was HTML publishing pages to the web. When it came to web publishing, figuring out the role, if any, Office would play was much more difficult. The internet was quickly splitting into two camps. There were those who were hand-crafting sites in HTML. Using basic text editors they pushed the limits of HTML to do everything in the browser—going all in on native HTML, which at the time did not even support basic tables or much of anything. Then there were those who would navigate with HTML until at the very end a link pointed to non-HTML documents such as PDF files (almost like the eventually extinct Gopher application), particularly inside the earliest corporate web servers called intranets or the new consumer web sites from print magazine publishers

Our approach was to find ways to use Office to create HTML content so it could be viewed in browsers even without Office—in a sense the idea was to turn the World Wide Web into the next generation printer or workgroup file server for Office. Except we had two big problems. First, HTML was too minimal to support any common business documents, even as a “printer” so to speak. Second, from a PC there was no way to emulate the Save dialog to save a file to a web site. As much as we had a vision for these intranets, the technology was not there yet. We had to invent something.

The Internet Assistants across the apps bringing HTML add-ins to market for this “print-to-the-web” scenario was a level of agility that Office had not yet exercised, with much of the work happening while both Office 95 and Office96 were under development. A key person in those efforts was Kay Williams (KayW), a program manager on the Word team who had worked on getting Word’s first Internet Assistant to market just in time to beat Netscape 1.0.

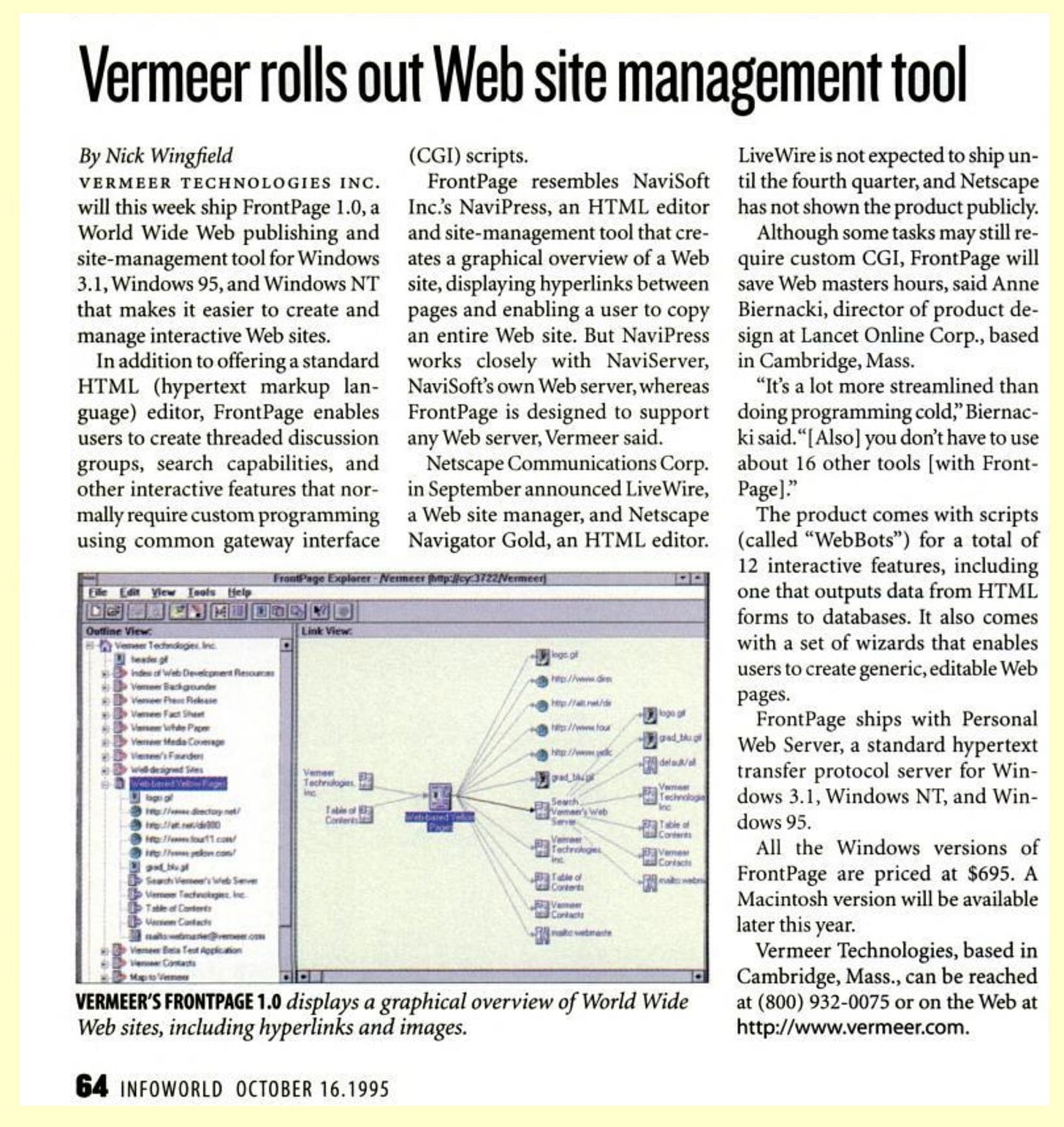

At one of the internet conferences in Boston, Internet World, in the fall of 1995, Kay spotted the demonstration of a product called Vermeer (named after the artist) by the company cofounder Randy Forgaard. Kay fired off mail to the Word team highlighting Vermeer’s WYSIWYG HTML Editor (What You See Is What You Get, an editor that showed what the end result would look like while the document was being created). The product was especially clever. It not only edited HTML pages, but it had a new model for managing a full website collection of pages.

Nothing like that had been done before.

The technical challenges of typing a web page were understood, but no one had invented a way for less technical people to create a whole site. A site needed a home page, navigation aids, and a way to link all the pages together. This was something that many of us were experimenting with at the time as we all raced to register domain names based on our last names or other pet projects. Creating web pages was tricky enough but managing a collection of pages and especially doing basic things like collecting information from a form were equivalent to programming. Vermeer seemed to address this. I had been using early versions of the HTML assistants to share digital photos (taken with the Epson PhotoPC, one of the first consumer digital cameras, which I had found for BillG to give as a gift to the exec staff one holiday). I pulled together a bunch of photos and created a PowerPoint HTML slideshow. I did this for a trip we took to the USS Ohio nuclear sub in Bremerton hosted on my original sinofsky.com. That was the early world-wide web.

Several of us tried the Vermeer product and were all impressed. We later learned Vermeer was keenly aware from its server logs that Microsoft people had downloaded the product, decidedly something we were not used to. Sitting in ChrisP’s office he was pondering the idea of approaching the company to see what could come of a relationship with them. Chris was many things but not usually spontaneous, so for at least an hour we rehearsed a “cold call” to the company CEO with an offer to simply meet and see a demonstration. It was kind of exhausting and very ChrisP.

After some discussion and rehearsing the call, ChrisP picked up the phone and dialed directly to Charles Ferguson, the CEO. Much to Chris’s surprise, Charles picked up the phone. At first, I don’t think Charles believed the vice president of Office was calling. Chris was probably more nervous, even though he joined Microsoft when it was tiny he had mentally transitioned to being used to Microsoft scale. Since PowerPoint, the Office team had not done any M&A, and it was certainly new to Chris and me.

After chatting for a bit about how excited he was to see the product, “HTML for the masses” and describing how much the design and feel of Vermeer reminded him of an Office product, Chris invited Vermeer to Redmond. We would have gone to Cambridge but they were just as happy coming out here. By this time, we had already demonstrated the product to BillG and Chris made a point of telling that to Charles. Chris was convinced Microsoft should acquire the company.

Microsoft was not a particularly acquisitive company. Since going public, Microsoft averaged less than one deal per year. The Applications group had done only a single deal, but it was a huge winner—acquiring Forethought, Inc., the makers of PowerPoint. That $14 million dollar deal (Microsoft’s revenue at the time was $345 million) and the way the product was integrated into the company, set the bar very high for Apps.

None of us were well versed in the intricacies of venture capital nor did we know at the time two important facts. First, Vermeer was in the process of fundraising, which might not have mattered except it had a big impact on the purchase price of a company (I vividly remember having this explained to me). Second, one other company had called and expressed interest and that was Menlo Park–based Netscape. Marc Andreessen was also going to be visiting the company.

Charles Ferguson and co-founder Randy Forgaard arrived in Redmond. It was nerve-racking for all of us. The two were as awed by the scale of Microsoft as they were petrified of the Microsoft reputation that preceded. It turns out Charles was somewhat skeptical of Microsoft as a company. Prior to co-founding Vermeer, Charles authored the book Computer Wars: The Fall of IBM and the Future of Global Technology, which among its chapters describes Microsoft as having a strategy focused on locking customers into products.

Nevertheless, the demonstration and the team were a hit. We had arranged a fancy steak dinner at the Seattle institution, Daniel's Broiler. The conversation, at least our side, was rehearsed and practiced days before. We had no intention of trying to extract information or anything more than size of the team and so on—we had decided the product was exactly right, “105% of what we had been thinking” Chris repeated from the phone call. We were trying to get to the next stage of a deal. Chris had developed a salvo that went something like, “We would love to work with you more closely. We might consider anything ranging from a lightweight marketing arrangement to a source code sale or perhaps all the way to possibly the full meal deal.” Much to our surprise, Randy and Charles did not skip a beat and were open to acquisition, even downplaying lesser options.

And like that, Chris and I found ourselves totally in over our heads negotiating the purchase of a company. We enlisted the help of Microsoft’s treasurer and soon-to-be CFO Greg Maffei (GregMa)—my former office neighbor when I worked for Bill. Greg quickly educated us on all sorts of things we did not know about: Series B financing, percent ownership, pre-money, and more. Greg even came up with some clever idea of a bridge loan in case they needed payroll, in an effort to reduce the need for them to raise the next round.

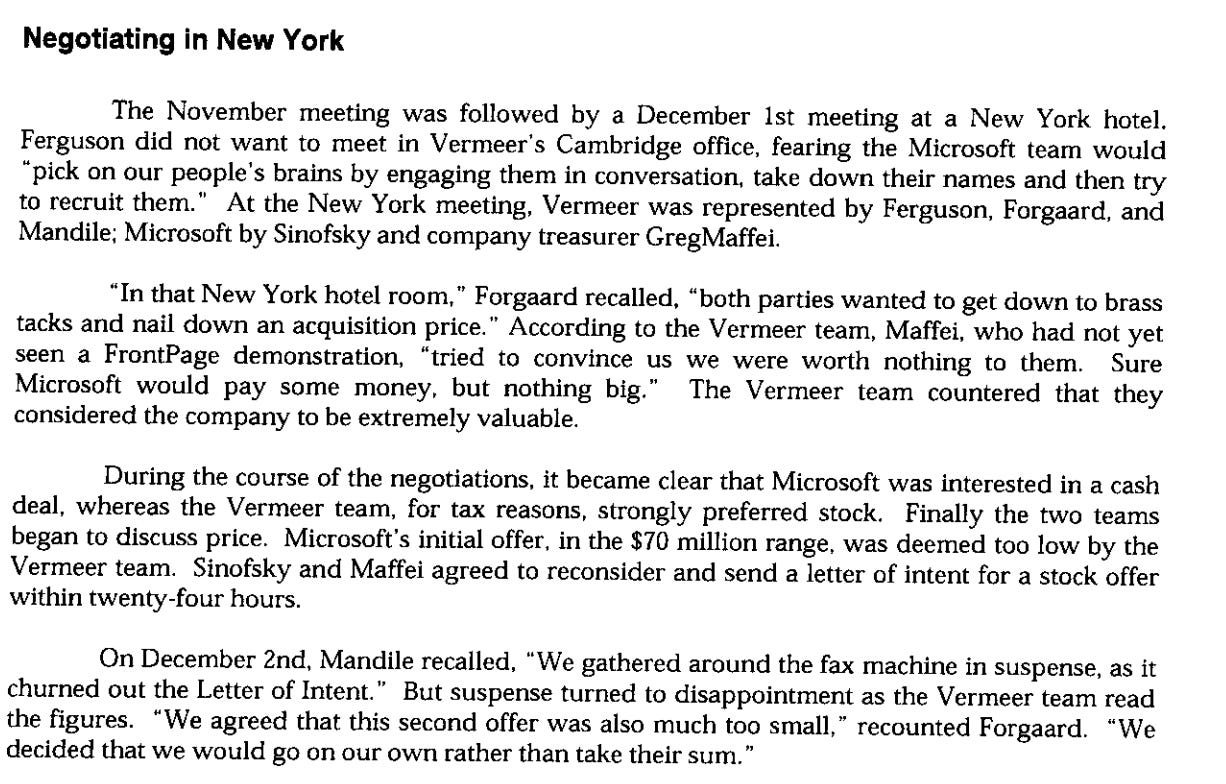

With the help of Greg, we met in the fanciest boutique hotel I had ever seen in New York City (GregMa picked it out) and negotiated over a pot of coffee that cost $80. It was an amazing experience to watch Greg negotiate the deal. We did not reach a final offer in the room, which was Greg’s strategy. We flew back, agreeing to send a new offer in 24 hours. The response to the next offer was not a yes. We were worried. We did not know it at the time, but Vermeer was worried too.

In the midst of the negotiations, on December 7th Microsoft held a briefing, Internet Strategy Day, for the press at the Seattle Center. It was a huge event with international press, not a single one could resist the Pearl Harbor theme. The big news was the licensing deal for Java crafted by the platform team. Among the many demonstrations and strategy slides, Office would demonstrate the role intranets would play in the modern workplace. Our team had prepared a “vision” demonstration that I did on stage with BillG. The key features included publishing to websites from future Office tools.

The Vermeer team saw exactly how committed we were to web publishing and the internet. They also concluded, though did not share at the time, that joining forces with one of these companies would be a better way to achieve their vision than competing head-on.

We started to get worried and knew they were also in talks with Netscape. That was enough to pique the interest of PaulMa in Platforms. Charles pressed Chris that a deal could be had and offered to fly back to Redmond to do a demo for BillG, PaulMa, and other key executives (he was specific). He did, on December 8th. That demo by Randy sealed the deal, probably as much as the body language and Randy’s impressive demo skills and passion as it was about the interest from Netscape.

A little more back and forth and we had a deal, and Netscape lost out or passed or whatever. For a brief moment, it seemed very cool to us that we had won out even if we kind of also felt it was our deal to lose. I mean we were Office. It felt a bit weird to be so focused on such a tiny company among all the scale of Office, but we were deeply convinced that web authoring was a future for Office.

Just after the papers were signed, I flew to Cambridge with Chris to help to make a good impression with the team, at least we hoped. The success of the deal relied on successfully hiring almost everyone and also moving to Seattle. That’s how deals were done then. I had previously visited companies at this stage and knew how tense employees could be. The fact that Microsoft was viewed as a cross between The Borg and a Death Star did not help. When I visited Intuit at this stage, some things our group said about culture did not go over well, so at least I had those lessons. Chris of course was masterful, as he was one of the most tenured and respected engineering leaders who had progressed to lead the biggest business at the company. I filled in with details of strategy and other details, most of which I said Chris would be handling and no one had to worry. Most of the team had read mainstream press and certainly everything in the industry was skeptical of Microsoft on many dimensions. The just-published Douglas Coupland book, Microserfs, was making the rounds and that didn’t help either. Generation X was much better, but I digress. I found myself trying to unwind serfdom and settled on ordering copies of the just completed Microsoft Secrets: How the World's Most Powerful Software Company Creates Technology, Shapes Markets and Manages, even though I disliked the title. We cooperated with the professors writing this book and I found it to be an accurate and detailed description of how products were built at Microsoft at the time.

Most all of the engineering team ended up making the move, which was a huge success. Several could not relocate due to family reasons and were offered roles in the regional office.

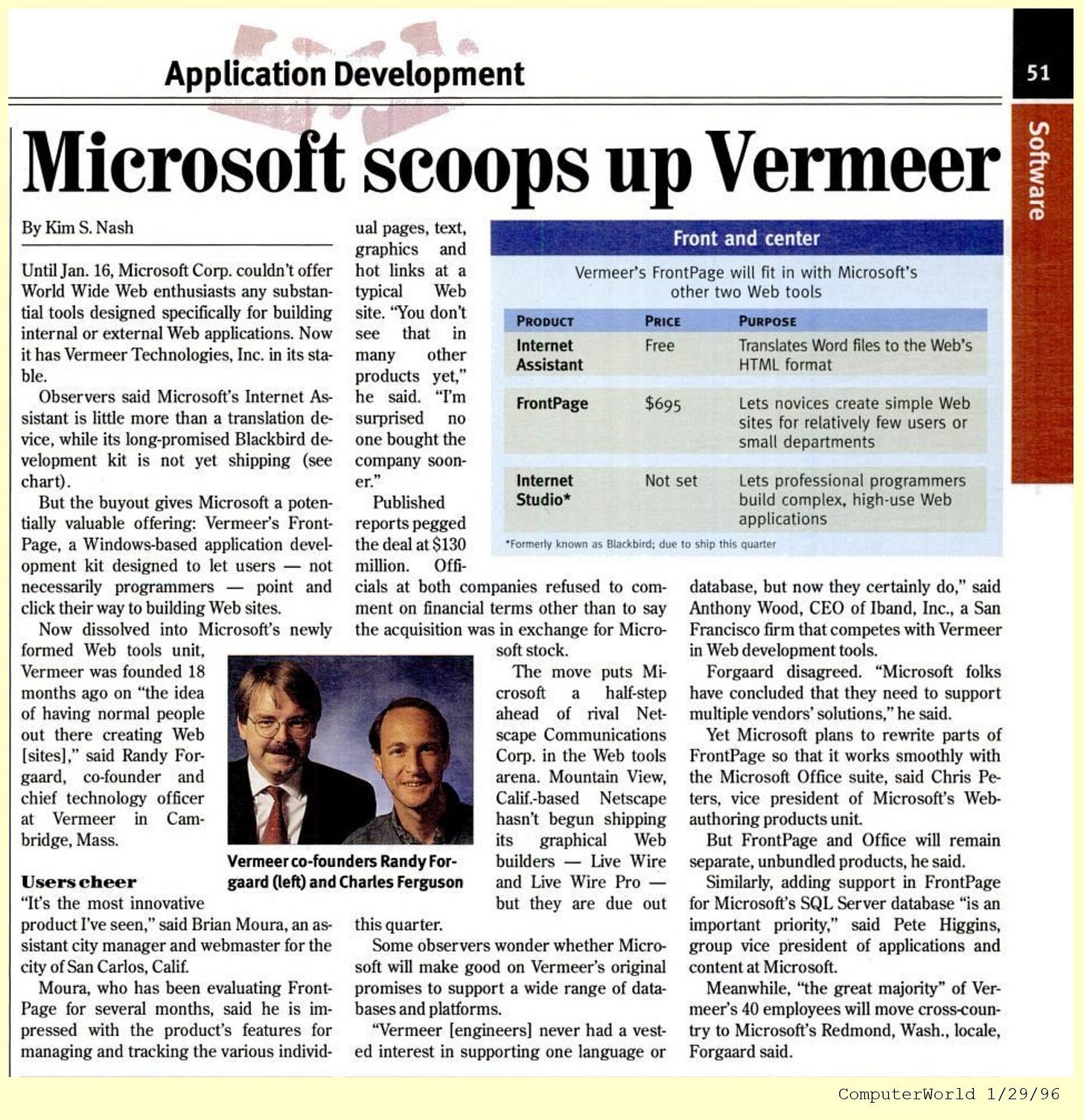

The deal was announced on January 16, 1996. It was announced for $130M, almost ten times the PowerPoint deal and an enormous deal for Microsoft at the time. We watched the stock price that day, though we rarely did, and it was up enough at the announce to pay for the deal. Having just finished the crash course in venture funding and deal-making, we then began our crash course in M&A regulation and learned about all the FTC filings and the process. Microsoft was under investigation for antirust and everyone was quite worried, as just a couple of years earlier a deal to acquire Intuit, makers of Quicken, was scuttled due to regulatory concerns. We worked through the process and won approval. We got a real kick out of the requirement that Vermeer would need to remain an independent company, in other words Vermeer.com for email and the web site, and other accommodations such as which entity would own the source code.

ChrisP decided it was time to dive back into code and return to the engineering and product scale he loved. He dedicated himself full time to Vermeer, leading the team as VP of FrontPage, complete with a new Vermeer business card. He was incredibly energized and even wrote code. He quickly added an Insert Hyperlink dialog to match the one in Office.

What ChrisP did was an example of a golden rule of any acquisition—always have someone of seniority willing to bet their career on the outcome of the deal. That means someone willing to change jobs, integrate themselves into the appropriate place in managing the deal, and signing up to be there until the next logical step (almost always further integration into a broader organization or the separation of the business into something needing a distinct CEO role). To his credit, ChrisP signed up for that role. To many it looked like Chris walked away from a big job in Office. Though to Chris—developer on DOS 1.0, Mouse 1.0, Windows 1.0, and so on—this was a logical progression and Office was the diversion from his path of shipping and innovating entirely new to Microsoft products.

The strategy was to quickly turn around a released copy of FrontPage, packaged in a standard Office box, and get that on shelves as soon as possible, which they did. This FrontPage 95 (Vermeer 1.1) made it into market and in short order became the leading web authoring tool, selling over 150,000 copies in a few months, substantially more than the 275 copies Vermeer had sold as an independent company.

Once that release was complete, ChrisP began the long-term integration of FrontPage. The biggest concern was losing momentum in what he believed was a next big category for Office. In some ways, PowerPoint offered a good lesson in integration. For the most part the team continued on their mission, only prioritizing getting a Windows release out quickly. The whole divisional transition to Office also changed PowerPoint from an independent, so to speak, operation to one more integrated. Even then it was a peer to Word and Excel, albeit remote.

In the short history of acquisitions, Microsoft could be said to have roughly three modes of venture integration. The most common was to simply absorb the code and team into an existing group or product. Microsoft just completed a series of acquisitions in graphics, for example, and those in some form (or not) went on to become parts of or team members of the underlying graphics technology for games on Windows. Similarly, several acquisitions were done in e-mail and networking, landing in their respective teams.

A second type of integration, far less common, was to acquire a company in a space Microsoft hoped to lead and to put forth the product as the new leader. These tended to be less successful during this era, perhaps because of the way the sales efforts were transitioning to business licensing from either retail or distinct sales motions for each product. The company was becoming a Windows, Server, and Office machine and whole new products would struggle to fit in if they were not part of these efforts. A big challenge with these deals was the ever-present goal of synergy across Microsoft. The pressure on visible leaders to also show integration with Microsoft, especially to leverage sales efforts, was rather intense. Additionally, there was the pressure to build more on the next generation technologies Microsoft was building. SoftImage was acquired to enter the television production space for $130 million, but Microsoft lacked a structure that could capitalize to grow the asset. HotMail was acquired for over $500 million in 1997, and from the start it was a leader in free email but also in constant synergy negotiations with Exchange and ongoing pressure to build on Windows server. This pattern would repeat many times for many future acquisitions. The logic behind this integration strategy is always something along the lines of “this is a great company, but we can make it even greater.” In reality, most leaders seemed drawn to this approach, declaring the acquired product a new leader, because that brought with it all the attention and glory of being a leader having simply done a deal.

A third type of integration, and by far the most difficult, was what I would call sheltered. The company was acquired and the product nurtured as though it was going to be a new leader, with a specific integration agenda and a strong sponsor that tightly controlled all the inbound requests for synergy. I hate to describe it this way, but you could picture essentially building a bubble around the team and offering outsiders (to the team) very specific points of integration. Executing on this strategy while not simply telling every other group to drop dead was both an act of diplomacy and heroism, and enormously self-sacrificing. As we know today, this is almost always the right way to do venture integration and when everyone agrees the painful bubble is replaced by standard operating procedure. The logic of this mode of venture integration is easy to see — “this is a great company and we acquired it because it is great and the team should keep making it even greater, just ask where Microsoft resources could help.” The emotional costs of such a strategy in a company dominated by strategic synergy and sales efficiency were high and few had the clout to pull it off.

ChrisP had the desire and clout to build a bubble around Vermeer. Inside the Office team we knew to basically leave FrontPage alone and unless Chris or one of the senior people came asking, we just assumed they were doing what was right. As the development of FrontPage 97 continued, many points of integration came about, but with few exceptions these were done via the negotiated portals through the bubble.

Chris and the team found themselves drawn to many potentially strategic discussions, however, and those created quite a bit of stress. It is easy to imagine that everyone had their sights set on either leveraging one part of FrontPage for their product or expanding the strategic importance of their technology by convincing FrontPage to adopt it. At the same time, few teams saw the beauty of the whole of FrontPage, an integrated view of designing, creating, and managing web sites.

Some teams wanted to use the incredibly novel ability of FrontPage to publish pages and content to the web. This resulted in a technology that many of that era remember, the FrontPage Server Extensions, which became a standard offering on most web-site hosters. These even ran on Unix back in the day, which was quite controversial at a time when helping Windows NT to win in web hosting was key. Other teams wanted to add HTML editing to their tool and so it was natural to request the editor component of FrontPage as a chunk of reusable code, something that BillG would be proud of. Things are rarely that separable. Internet Explorer was also working on adding editing at the time (as was Netscape). Many meetings were held explaining how much more difficult WYSIWYG editing was, even if it was for simple HTML. It was clear the FrontPage team were probably the world leaders in Office-level HTML editing, which made these conversations awkward.

The team soldiered on working within the bubble that Chris had so carefully crafted. He was under enormous pressure and at the same time was happily coding away his features in the product. It was amazing.

To help to scale the team, ChrisP also built out the program management (product management in modern Silicon Valley vernacular) function of which Vermeer came with none, say for Randy the co-founder as is common with most startups today. ChrisP assembled a PM team from several members of Office, with a lead from Word who had originally detailed the depth and richness of FrontPage. Chris also brought in a leader to build out the test function and a marketing leader, thus making Vermeer equivalent to a well-staffed Office application along the lines of the old product unit model, before Office. Vermeer was a self-contained unit with the functions needed to create a stand-alone product and business.

As the team would learn, bringing PM into a development centric startup was not nearly as easy as one might think. Our view was always that PM was there to help make development more effective and not to waste time, and importantly Apps viewed the approach to PM as something that contributed significantly to the success of Word and Excel. PM would often handle all those inbound requests for help and so on. The Vermeer developers, however, felt pretty good about their ability to select features, prioritize, and specify interaction models—after all they got this far and did well enough to be acquired. There was a tendency to think of PM as process over substance, a not uncommon view among many outside of how Apps had evolved the role. Building out the PM role while continuing to build the product, was one of the more challenging aspects of venture integration.

For many years, the integration of Vermeer would be the case study for Microsoft in how deals could be discovered and executed. Harvard Business School had a six-part case taught over two days to first-year students. Reading the entire case is one of those times when the case method is able to tell a great story and anyone wanting to read all the details as told to a Harvard Business School professor and researcher would find it enjoyable and worth the effort.

As it would ultimately turn out, however, the viability of a stand-alone web-authoring tool would be subsumed by many different categories and brought to market as a part of a variety of products. The web was still young and moving fast in many directions. While FrontPage did not endure as a stand-alone product, most all the members of the team went on to remain and contribute significantly to Office and as leaders in both editing and web technologies. In that sense, Microsoft got an even better deal than originally envisioned.

Every time I have WordPress pangs 😣 I yearn for FrontPage. 😔

This makes me want to re-read “High Stakes, No Prisoners,” Charles Ferguson’s account from the other side, of building the company up through (I believe) deal closing. It’s been perhaps 20 years since I read that book so the details are hazy but I remember it being very enjoyable.

Really enlightening to read about the integration that happened after the closing here and about the deal from Microsoft’s side!

Incidentally, I’m not sure the HTML authoring problem was every properly solved. I suppose it split into simplified server side tools for consumers (e.g. Squarespce, Blogger) and specialized tools for creatives (DreamWeaver). I always admired that FrontPage tried to provide the best of client and server.